11 July 1708

War of the Spanish Succession

Pro-Habsburg Forces under The Duke of Marlborough approx.70,000-90,000* with 52 guns

Pro-Bourbon Forces under the Dukes of Burgundy and Vendôme, approx. 85,000-90,000* with 70 guns

Location: 50°51′N 3°36′E . or search for Oudenaard, Belgium

Weather: Clear and seasonably warm. Rain starting at around sunset.

Sunrise: 04:44 Sunset: 20:57 Moonset: 13:57 waning 46% so there was effectively no moonlight that night.

(calculated from U.S. Naval Observatory from lat/long and date, if DOGE hasn't shut this down by the time you read this)

This battle, Oudenarde, stands out as one of Marlborough's Big Four in that it was uncharacteristically the only one that could be classified as a modern "encounter" battle. The other three were all set pieces, as classic battles had been up to then; where both sides deployed on a chosen field of battle. Oudenarde came as a complete surprise to the French, who had to hustle up to respond to Marlborough's unexpected crossing of the Scheldt River south of them. And Marlborough had to place his pieces only as they came up throughout the afternoon. So it developed piecemeal.

Stage of the battle as it really started to get going, about 1800. For larger view of the map, scroll down.

After six years, no end in sight.

So it was now 1708. Six years of war. Sigh. With

awful and seemingly endless wars like those pointless ones happening in our time, one can empathize with people suffering from the cost of this one. And the local people on whose land it was fought and devastated had probably forgotten or cared what this war was about in the first place. (Who was going to succeed to the Spanish throne, a Habsburg or a Bourbon...oh right...now I remember!)

In this particular theater, the former Spanish Netherlands (or French Flanders, now Belgium) the local population did not feel particularly liberated by the Allied forces of the British, the Dutch and the Germans, who tended to loot their farms and level their towns. So the Allies, probably even more than the French, felt like they were the ones in hostile territory. This would blow up in Marlborough's face during this 1708 campaign, as we'll see.

|

| Marlborough as a young man I prefer this portrait of him because he was only 58 at the time of the battle,a young man to me. by John Closterman |

Anne, Sarah, John, and Sidney had been close friends for years. They referred to themselves when Anne was a young princess as "The Cockpit friendship" and had pen-names for each other (Sarah's was Mrs. Freeman and Anne's was Mrs. Morley). But eventually Sarah's incessant pestering of Anne and the "mean girl" back-stabbing by Sarah's cousin Abigail Masham in cahoots with the slimy Robert Harley finally soured the Queen on her old friendship with the Churchills (particularly Sarah) and Godolphin. Sorry if I sound partisan.

But Marlborough's resignation caused a loud outcry from England's Allies (the Duke was considered practically a superhero by them). Locally the majority Whig party in Parliament, who were in favor of continuing the war, also wouldn't stand for it or for Godolphin's dismissal.. As a result, Anne was forced to accept Godolphin's and Marlborough's return, as well as the ouster of all the Tories from her cabinet, including Harley (not yet publicly a Tory but working undercover with them). For the first time in British history, the prerogative of the Crown to choose their own advisors was surrendered to Parliament. And Anne never forgot the insult. To her, she had been betrayed by her old friends. Wish I could've gone back in time and told her to suck it up--then quickly hit the button on my time machine and returned to my present before she had time to throw me into the Tower. But then, in our own time, I've seen even pettier behavior from our own leaders (not naming any names).

Marlborough returned to the Continent in the spring, exhausted by the political infighting back home, and paranoid about the stability of his office as Captain-General of the Allied forces. He neither considered himself a Whig nor a Tory. Like Dwight Eisenhower two-and-a-half centuries later, he saw himself as above politics. He was aware of politics and sensitive to the issues of all the parties, but he saw himself as above internecine partisanship. His cause was the higher fight against French autocracy and hegemony. But he was criticized by contemporaries for his close friendships with key people in all parties, even some fighting for the French (like the Duke of Berwick, his nephew). To him, diplomacy depended on friendship, even if you disagree...even if you are officially enemies.

Marlborough was tired, though, and wished for a negotiated peace. The previous year seemed to squander the otherwise decisive victory of Ramilles in 1706. There had been setbacks in Spain, an abortive attempt to capture the French port of Toulon on the Mediterranean (which, did, though, force the French to burn their own fleet to keep it from falling into the hands of the Allies), a separate peace in northern Italy between the Habsburgs and the French, and a stupid and distracting campaign on the part of the Austrians to conquer Naples (really? Naples?). But though the war seemed to be stalemated, the Dutch were not budging in their long demands for a permanent Barrier across Flanders. And the Habsburgs were equally adamant that Louis XIV give up his grandson Philip's claim to the Spanish Throne. Though he himself was tired of the war and the economic costs on France, both these demands from the Allies were a non-starter for the Sun King. The last things he would tolerate were the Dutch on his northern border or a Habsburg king of Spain.

|

| le duc de Vendôme at 50ish by Hyacinthe Rigaud |

| ||

| le duc de Bourgogne at 18ish by Hyacinthe Rigaud c 1700 |

The campaign begins with some head-fakes.

Both sides spent the spring building their forces back up and planning their moves. Vendôme's idea was to head-fake Marlborough in a number of directions but then to move east to capture the fortress of Huy on the Meuse River. This, he reasoned to the king, would force Marlborough to rush to defend that vital town on that river, trigger a climactic battle to undo the humiliation of Ramilles, and compel the Habsburg allies to sue for peace. Louis eventually concurred and authorized his marshal to do it.

On the 1st of June Vendôme began to move from Mons (see campaign map below) toward Brussels, as if to threaten that Allied base. Marlborough had positioned his forces between Brussels and Mons to block the French. But Vendôme kept moving to the southeast of Brussels, to Braine-l'Alleud (of later Waterloo fame), This had been a similar move made the year before, and as with that threat, Marlborough moved his army back through the capital and to prepared positions at Louvain to block Vendôme.

For his part, Marlborough wasn't yet ready for the head-on battle he had planned for and didn't take the bait. His numbers were, at this date, far inferior to the French army. His reinforcements hadn't fully arrived from England after much of his infantry had been diverted to the homeland in anticipation of a Jacobite invasion of Scotland to regain the kingdom for the Pretender, James Francis Edward Stewart (James II's son). Louis funded that invasion attempt thinking that the Union Act, uniting England and Scotland in 1707, would anger enough Scots to rise up against England. This invasion turned out to be a flop (like a later one I wrote about in 1746), but it served as ruse enough to delay the Allied mobilization in Flanders.

Marlborough's plan was also to have Prince Eugene bring his army of 40,000 west from the Moselle, as sort of a reciprocal favor for his own move east during the Blenheim campaign in 1704. But Eugene was over 150 miles away on the 1st of June and didn't get started until the end of the month, when he finally got approval from both the Elector of Hanover and his boss, the Emperor. It would take at least ten days for his cavalry to make it to Brussels and two weeks for the infantry, totaling just 15,000 men. The Elector, incensed that his theater was to be dismissed by the Alliance as inconsequential, demanded that Eugene leave the majority of his army behind. So even if Eugene did arrive, his reinforcements would not be enough to check the larger French army in Flanders. He himself hurried west with a small bodyguard of hussars, eventually followed by his 15,000.

For the French part, they wasted the whole month of June doing nothing. They might have used their numerical superiority to attack Marlborough up by Louvain, but they just sat in front of Brussels for weeks. Apparently Vendôme and Burgundy were arguing about the best course and corresponding with Versailles about what Louis's advice was. Though Vendôme was still all for moving on Huy, Burgundy was for striking to the northwest and taking the towns of Ghent, Bruges, and Oudenarde, cutting off the Allies from their contact with their coastal bases and forcing a battle up there. Though he had originally been persuaded by Vendôme's Huy Plan, the Sun King had second thoughts about it, fearful of exposing the western sector of the French lines in Flanders and of what Eugene's movements out of Germany would be. He ordered Vendôme and Burgundy to hold off on either of their plans and, instead, threaten Brussels, waiting for Marlborough to make the next move and for the developing intelligence about Eugene. Not exactly a blitzkrieg.

Then a nasty surprise!

Finally, on the 4th of July, the French joint commanders got a go-ahead from Versailles to execute the plan proposed to the king by Burgundy, to make a sneak attack and take Ghent, Bruges, and Oudenarde. Taking advantage of the disaffection of a significant part of the Flemish population with the Allied occupation, they had been conspiring with certain pro-French factions in the strategic towns of Ghent and Bruges to defect and open their gates to the French. Vendôme thought the venture too risky and opposed it. But with the letter of approval from his grandpa, Burgundy took it upon himself as co-commander to start moving the whole army northwest the night of the 4th, crossing the Dender River on secretly prepared bridges at Ninove, and reaching the gates of Ghent on the afternoon of 5th. To the surprise of the Allied garrison there, the gates were opened by the townsfolk and the French army flooded in, forcing the 2,000 of the Allied contingent into the citadel, where they surrendered the next day.

That same day the French rear-guard under d'Albergotti at the the army's original position in front of Brussels, was making a

theatrical display of marching back and forth with false regimental

flags, miming the main army as if it were preparing for battle and

fooling the Allies about the movement of the main force toward Ghent.

This ruse was also used by the Confederates during McClellan's

mismanaged 1862 Peninsula campaign in the American Civil War, with the

same forestalling effect. And also, as we'll see, by Marlborough in payback in the upcoming battle.

Also on the 5th, in the pre-dawn hours, a force of French under Lamotte making a forced night march was let into Bruges, 24 miles (39 km) to the northwest of Ghent and commanding the main canal to the Channel Coast. In a stroke the Allies had lost two important cities, strategic for their position astride several waterways to the coast and the north. Suddenly Marlborough's entire army was vulnerable to being cut off from home base.

This couldn't have come at a worse time for the Captain-General. Maybe it was all the stress he felt from the politics at home. Nearly every day,he received bitchy letters from his wife about her waning influence with the Queen. Maybe it was anxiety about when Eugene would show up with his reinforcements. Maybe it was all the nagging he was getting from the irritating Dutch political representative, Sicco Goslinga, a politcal hack serving as a kind of commisar representing the States-General. But when he heard the news of Ghent's and Bruges's fall, he simultaneously developed one of his chronic migraines and caught some sort of bug, which knocked him down with a fever. You might say he succumbed to stress (well, ya think?). The timing was unfortunate but predictable. And if you've suffered from migraines (which Marlborough had a history of), you know they're not just a bad headache. They are agonizing; even light can make them worse. So he might be forgiven if he just checked out during this crucial time on all this bad news.

But he didn't. Though he was laid up in his tent, he still managed to get out emergency orders to his key generals, like Cadogan, Argyll, von Bulow, Tilly, and Lottum. He dispatched Brigadier Chanclos with 900 additional Dutch and German cavalry to reinforce Oudenarde, 15 miles (23 km) south of Ghent. Then he ordered the army to assemble at Assche, 8 miles (13 km) northwest of Brussels, with minimum baggage by the 7th. By this time, Eugene had galloped into Brussels up alone, without his 15,000 reinforcements, but they were a few days behind him. Even by himself he gave Marlborough such encouragement and said this was the time to catch Vendôme with his pants down--to hell with reinforcements! This hug from his old friend was the tonic the Duke needed.

Then, still sick but bucked up by his soul mate, Marlborough got on his horse and rode out to lead the forced march as fast as possible down 25 miles (41 km) to Lessines on the Dender, 16 miles (26 km) southeast of Oudenarde. Eugene was right: if the French were going to try and cut him off from his lines of communication to the coast, he was going to do the same to them and their lines to their bases in Tournai and Lille. Let's see how they like it?

Now Marlborough pulls a fast one.

Well, Vendôme and Burgundy didn't like it. But neither did they expect Marlborough to be able to move so fast. Though the two stole a march on Marlborough by capturing Ghent and Bruges, they proceeded to waste five days debating about what to do next, typical of their lack of cooperation. Messages were sent to Versailles asking for guidance. Vendôme himself wanted to invest Oudenarde and capture that last big town on the Scheldt to finally cut off Marlborough from the Channel Coast. This seemed like a wise, strategic move. He led half the army down to begin laying siege to Oudenarde from the northern side of the river. Chanclos, the Allied commander whom Marlborough had sent to reinforce Oudenarde, warned the townsfolk that there would be mass-hangings and he'd burn the whole city to the ground if there were any repeat of the treachery of Ghent and Bruges. They apparently just went about their business.

For his part, Burgundy wanted to move down to Lessines and secure that crossing over the Dender River so Marlborough couldn't use it to relieve Oudenarde or come between the French and their own bases in Lille and Tournai. But, as I said, he had to wait to hear from Versailles first. Since the king had not formally named either Vendôme or Burgundy as paramount commander of the army, neither thought he was bound by the other's orders. On the 9th, Burgundy got permission from Louis to act on his plan to march down to secure the crossing at Lessines. For some reason, the king thought Marlborough was moving southeast in the direction of Charleroi and Namur and that this move by his grandson was the most prudent. But this is just another example of the flaws in the French command structure, since neither was in charge, they had to wait for guidance from a king 200 miles away, in an age before even the telegraph, much less Zoom.

On the 9th, with his official go-ahead in hand, Burgundy moved the bulk of the French army down from Ghent toward Lessines to secure that crossing over the Dender. But as his advance cavalry got near the town, they discovered that Marlborough's advance guard under Cadogan had already occupied it and was throwing bridges over the river. So Burgundy pulled back toward Ghent, where he and Vendôme continued to waste time-- camping at the town of Gavere on the Scheldt--debating what to do next. Vendôme was ticked at Burgundy's timidity and wanted to swarm down on Marlborough's advance guard at Lessines and annihilate it in detail, securing the Dender. But Burgundy again wouldn't cooperate and thought it was too risky. He suggested they send for instructions from Versailles again. Vendôme thought, if they were going to do that, they should at least cross over the Scheldt at Gavere to set up a battle position on the heights above the Norken stream north of Oudenarde. If Marlborough wanted a battle for that town, it was best to occupy the strongest position overlooking it.

Meanwhile, not wasting any time himself, Marlborough, now aided by his old friend Eugene, and his able general William Cadogan, ordered a night march up from Lessines toward Oudenarde. His army began to arrive there about noon on the 11th, having marched 60 miles in two days. Exhausted as they must have been, the Allied troops kept marching. Their anger at the French and the treachery of Ghent and Bruges fired them and that gave them added stamina.

_by_Nicolas_de_Largilli%C3%A8re.jpg) | |

| General le duc de Biron by Nicolas de Largillière 1714 |

Well into the morning of the 11th, French foragers northeast of Oudenarde near the town of Eyne (see map below) noticed quite a lot of activity down by the Scheldt River. Earlier that morning Cadogan's advance guard had thrown five pontoon bridges over the river just downriver of the city and by noon were hustling over them. Word was sent back to the commander of the French advance guard, Lt.Gen. Charles-Armand Biron up at Heurne, who galloped down to Eyne to see for himself. He climbed its windmill and whipped out his spyglass. From that vantage Biron saw massive columns of enemy troops marching along the right bank of the Scheldt, crossing in force just downstream from Oudenarde. According to Burgundy, Marlborough was supposed to be way down in Lessines, at least two days away. There was no way his army could've made it all that way overnight. This must be just a scouting party.

Approximate site of pontoon bridges across the Scheldt looking toward Eyne, given that the course of the river has been slightly altered in 317 years. It's still not just a little brook. image from Google Street View.

But as Biron scanned the ground below him and across the Scheldt, it was obvious that this was no scouting party. It was Marlborough's entire army. Dust clouds could be seen far to the south. Redcoated infantry was seen deploying in several battalions just south of Eyne on the west side of the river.

Biron sent several messengers galloping back to Vendôme and Burgundy at Gavere, where the French army had begun to cross the Scheldt, about 4 miles away (7 km). Snapping his spyglass shut, he scrambled down off the windmill and moved his own infantry, seven battalions of Swiss infantry, to fortify Eyne at the Diepen stream. He also moved his twenty squadrons of horse down from behind Heurne to confront the eight squadrons of Rantzau's Hanoverian cavalry who had already crossed that brook. These gave a sharp fight, captured some French standards, but hastily retreated back over the Diepenbeek. Interestingly, these Hanoverians had with them the young heir to the Electorate who would become the future King George II, and had his horse shot from under him. He got out okay, though.

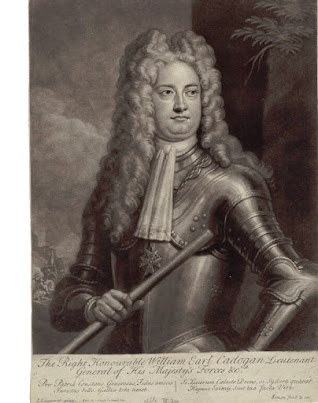

|

| William, 1st Earl Cadogan One of Marlborough's most reliable generals. Engraving by John Simon ~1710 |

Lt. Gen. Pfyffer, commander of the Swiss infantry in the French advance guard, had moved four of his battalions down to Eyne and started to fortify that place around 13:00. Vendôme had galloped down to Heurne to see the enemy activity himself, and sent back urgent orders for Burgundy to bring up the rest of the army from Gavere and attack the still-isolated Allied advance guard. He saw this was an opportunity to catch Marlborough with his feet on both sides of the river deal him a devastating blow.

But Burgundy, getting bad advice from his chief-of-staff, Lt. Gen. Puységur, that the Norken stream north of Heurne was unfordable (it wasn't; their own avant garde had forded it), instead had his army start to form up on the northern plateau above the stream. Puységur had also misinformed Burgundy that the ground south of the Norken was unsuitable for cavalry, in spite of the fact their own and the enemy's horse seemed to be galloping over it quite nicely.

Marlborough supervising the crossing over the Scheldt, with Oudenarde in the distance. I love how everyone seems to have a dog in these paintings.. I love dogs! By John Wootton

|

13:00-15:00 Hours. Showing positions to the immediate northeast of Oudenarde city. As with all of my maps, the actual footprint and uniform color of the regiments are represented, as well as the ordnance flags of the regiments. I had no information on the identity of the French cavalry regiments in Biron's advance command at this stage of the battle, other than there were some 20 squadrons (with some narratives citing only 12).

Marlborough, and his old friend, Eugene were in the thick of it, feeding in more and more troops as they came up from their crossing of the Scheldt. All afternoon, British and German infantry and cavalry arrived from their long march from Lessines and the two commanders worked together to deploy them into the front line, first from Groenewald down the Marollebeek and then, from Schaerken westward along the Diepenbeek (map below).

|

| French troops crossing the Norken stream. And, yes, more dogs! (Hey, little fella!) |

The view today from the approximate location of Burgundy's HQ at Royegem. Doesn't look that swampy or unsuitable for cavalry to me. (But then I've never been that adept at riding a horse; I usually just hang on for dear life.) Of course, that was over three centuries ago and I'm sure the land has been greatly domesticated. And also saw several devastating wars in this same countryside. Image from Google Street View.

This being said, I am somewhat confused about why, if Lottum was closely supported by Holstein-Beck's division, Marlborough didn't just have that fresher command hustle over to relieve Cadogan instead of risking the choreographed bait-n-switch. But then I wasn't there. Still it seemed like an over-complicated half-time show at the Rose Bowl.

At this crisis of the battle, it seemed things could have flipped either way. Eugene was fighting like mad to hold back the overwhelming numbers of French infantry pressing against his tiring troops. And he still wasn't sure about all the enemy forces he could plainly see just standing up on the plateau north of the Norken.

For his part, down on the left, Marlborough was also trying to hold back some 26 French battalions with just 18 of Holstein-Beck's. The French, including the elite Gardes Françaises and Suisses, were repeatedly charging across the little Dieppenbeek and being pushed back. And charging again. Back and forth the bayonet fight went on for hours. The Duke didn't know how much longer he could keep this sector from crumbling.

In a desperate gamble, around 19:30, Eugene ordered Natzmer to wheel his 25 squadrons of Prussian cavalry left and make a hell-bent charge against the French infantry and cavalry behind Hurlegem, to the north of Groenewald and in the fields just below the Norkenbeek. He felt reasonably secure doing this because, by this time he had both Lumley's 17 British squadrons and von Bulow's 35 squadrons to check whatever the French might try from the north. His reasoning was to distract the French command from the main fighting with an attack out of nowhere from their north and east.

At first the Prussian cavalry had a gloriously successful charge, overrunning two French battalions and a four gun battery. But other French infantry, hiding behind the hedgerows and gardens of Hurlegem, enfiladed Natzmer's troopers. Then Burgundy ordered a countercharge by the Maison-du-Roi. These rammed into the Prussians, now in disorder, and hurled them back the way they had come. Aside from the opening moves of the battle when Biron was trying to check Cadogan, this was the only offensive action the French cavalry was to execute that day, and these regiments, l'elites d'elites of Louis's army, were furious at having been held back the whole afternoon while the battle raged. So they wanted revenge on the bastards.

Natzmer himself was wounded by four saber cuts and only managed to escape by spurring his horse to make an Olympian leap over a ditch. Three-quarters of his command were killed, wounded, or captured. But as the French guard cavalry pursued the retreating Prussian , they saw the ranks of Lumley's and von Bulow's 52 fresh squadrons. They prudently reined in and withdrew.

Natzmer's charge may have been a disaster, like that of the Light Brigade at Balaclava or the fruitless charge by the Union cavalry I described at the end of my post on Cedar Mountain, but this one did have a critical, positive effect. It distracted Burgundy from what was unfolding on his right.

The traps snaps.

About 19:30 Overkirk had ridden over to personally inform Marlborough that his Dutch troops, 40 battalions of foot and 87 squadrons of cavalry, were now in position on top of the Boser Couter "hill", just east of the village of Oycke, ready to swarm down on the French rear. (map below)

It had started to rain and after several hours of accumulated smoke, it was hard to see what was going on to the west. Though Burgundy and Vendôme had plenty of idle cavalry, nobody on either of their staffs had apparently thought to send some to screen the hill northwest of Oudenarde. Overkirk had taken a route that was masked from the French, using sunken roads and the reverse slope of the Boser Couter. Also, Vendôme , as I've said, was so hip-deep in the close fighting to his front that he wasn't paying attention to the broader battle.

So when Overkirk stopped by to give Marlborough the news personally that his forces were in position, the Captain-General gave him the nod to commence his surprise attack. The French were completely surprised.

Tilly's cavalry charged from the northwest, sweeping away the few French horse up near the Norken stream. The Maison-du-Roi, having just rallied from their routing of Natzmer's attack to the east, were also completely routed themselves by Tilly's charge. Oxenstierna's 20 battalions of Dutch infantry swooped down on the French from the northwest. And Heukelom's 20 battalions hit them from the wes. These were supported by the 43 squadrons of Danish and Dutch horse, led by the 20-year-old Prince of Orange in his first battle. In all some 32,000 (more or less) came out of nowhere and hit the French on their unprotected right flank and rear.

Here again, in van Goslinga's fantastic report, the politician claims that Overkirk was also too timid to order the attack and that it was he, seeing what needed to be done, who heroically stepped up to personally lead the decisive charge on the French right. In his telling, he virtually won the battle of Oudenarde himself. He also later claimed it was he who single-handedly won the Battle of Malplaquet the following year. This guy must have been an inspiration for Baron Munchausen. Too bad he didn't have a Tik Tok account back then.

Situation at 19:30-sunset Marlborough's plan is completed as Overkirk brings the rest of the Allied army over the Sheldt through Oudenarde and around to envelop the western side of the right wing of the Vendôme's position. The left wing and reserve of the French army are still immobile to the north of the Norkenbeek.

View from Overkirk's position on the Boser Couter, looking toward the French right. from Google Maps

Reverse

view from approximate position near Burgundy's headquarters at Royegem

looking in the direction of the Bouser Couter "hill". Overkirk's troops

would've crested this broad hill (which seems like a generous term for it) to suddenly show up on the French right and

rear. Google Street View

|

| Marlborough saying hello to his French prisoners. And just look at those kettle drums! by R. Caton Woodville |

So it was a victory for the Allies, and another feather in Marlborough's hat (or tapestry hanging at Blenheim Palace). It wasn't nearly as bloody a battle as Malplaquet would be the next year, but it counted. The Duke wrote to his wife, Sarah, that night about the glorious outcome and at the end of it, thanked God for the victory and for allowing him to "bring happiness to the Queen and nation, if she will make use of it." But Sarah, the Queen's old friend, read the letter out loud to her old friend, Anne, and the Queen took offense at the last clause, "IF she will make use of it?!" She took it as a snide sarcasm that she wasn't appreciative of Marlborough's victories. She wrote to the Duke in fit of pique that she was sure "I will never make ill use of so great a blessing." Marlborough was acutely aware that his wife reading his intimate letter to her out loud to the Queen, their friend, had further eroded the trust from their lifelong relationship. He immediately wrote back a conciliatory letter to Anne which she took graciously. It wasn't "Mr. Freeman" with whom "Mrs.Morely" was peeved anyway, it was his wife, "Mrs. Freeman" (their original Cockpit pen names for each other in the "good ol' days") . But the old, intimate friendship they all had when Anne was a young princess had eroded. And it would continue to decay as time went on and as the politics escalated.

So Louis XIV survived both his son and his grandson (his other grandson, Philip, became Philip V of Spain when this war was over). It must have been so hard for him (even though he was a hated dictator). He died in 1715, outliving all his heirs but the five-year-old great-grandson Louis XV.

Special conditions for gaming this battle:

Tactical considerations

Different Fire Systems

I

know that those of you steeped in tactics of the 17th and 18th

centuries are aware of the competing musketry fire systems in this age.

How the English and Dutch had pioneered the three-rank, platoon fire

system while the French and nearly all the other Continental infantries

continued using the fire-by-ranks system, a holdover from the age of the arquebus. Whatever game engine you use, I would encourage you to

account for this difference as it would probably make an impact in a

wargame.

I would also encourage you to see my discussion and graphics on these two systems at the end of my Blenheim post from 12 years ago.

Formations

The

British and Dutch forces continued to deploy in three ranks for

infantry and two ranks for horse. The other allied forces, including the

Prussians, would deploy in four ranks for infantry and three for horse.

The

French, the slowest to evolve tactically, still used their formations

that had brought them so much success since the Thirty Years War,

seventy years before. Officially they were supposed to deploy their

infantry into six ranks, but as the frontage was to remain consistent,

and since the size of their battalions was, in many cases, somewhat below the authorized strength should be, they probably deployed

in five ranks. They also deployed

their cavalry in three ranks.

My maps reflect these dimensions in representing individual battalions and squadrons.

Artillery

At

this date, artillery was still manned by small crews of professional

gunners. Militarized transport did not yet exist and so the guns were

moved to the battlefield by civilian contractors, who would then take

their limbers, wagons, and selves back behind the main camp, out of

harm's way. Movement on the battlefield itself was done by bricole (dragging by ropes) by the gunners and borrowed infantry from the closest battalions.

It was probably partly for this logistical reason that Oudenarde, an encounter battle, did not feature many artillery pieces. Most of the guns of both sides were left on the other side of the Scheldt.

Terrain

While the ground was not unsuitable for cavalry as Puységur asserted, however, the terrain around the villages was lined with hedgerows, ditches, and walls. These would break up infantry and cavalry formations and would be used to strengthen defensive positions.

Likewise, the streams criss-crossing the battlefield were not unfordable. They were actually little more than shallow ditches.

Orders of Battle

These

data are based primarily on Kronoskaf's OOBs for the battle. The following is a key to each column.

Command is the name of the command or regiment, in its primary uniform coat color. Where known, this is followed by the regimental number it would eventually be known as later in the century, when the more obsessive-compulsive felt the need to numerically organize their armies. Where I could not find any reference to these uniform details, I have colored them the generic grey of the period.

“Facing”

The command level and type, using standard military symbology . This

column is color-coded in the “facing” color of the regiment. During the

WSS these would be primarily the colors of the voluminous cuffs. As

with the coat color, where I could not find any information on

regimental facings, I've also colored this cell neutral grey.

Flag A miniature of the regimental flag, if known. If unknown, this cell is left blank. You'll note that the British flags for this period had officially changed from the previous WSS battles in that there were the Acts of Union between Scotland and England passed by their respective parliaments in 1707, creating the nation we now know as Great Britain, or the United Kingdom. So the flags of each country (the red cross on white of St George and and the white X on blue of St Andrew) were hybridized into the form familiar (or almost) to the modern flag we know today.

“Nationality” Since each army was composed of allies, I've listed the country of origin of each unit. Now that the Scots and English were one people, I've called them British. But Scots and Irish and Germans were also incorporated in the French cause, so I've listed these regiments' ethnicity here too.

“Strength” For each unit I assigned the authorized full establishment at the time. However, I could not find a common, definitive overall present-for-duty for each unit in my sources and I assume that each army was not operating at full strength. While Kronoskaf gives the Allies 70,000, Chandler estimates 80,000, and Wikipedia (with its different sources) cites as many as 90,000. Kronoskaf gives the French only 62,000, Chandler 85,000 and Wikipedia the most with 90,000. For computing strengths for your own wargame OOBs, I recommend applying an average of these reported and apply the standard reduction from the full establishment cited here. Please do not cite this OOB in any formal academic paper. But you already knew that.

“Guns” The number of guns of all calibers available. However, very few actually made it across the Scheldt to participate in the battle. This was definitely not an artillery battle.

“Bns/Sdns”

The reported number of subunits (Battalions for Foot, and Squadrons for

Horse). The number of foot battalions present at the battle is fairly

reliable based on my references, but the number of squadrons is

conjectural--I've used the Kronoskaf estimate for this.

References

Paper/Digital:

Barthorp, Michael & Mcbride, Angus, Marlborough's Army 1702-11,

Men-at-Arms #97, 1980, Osprey Press, London, ISBN: 0-85045-346-1

Chandler, David, The Art of Warfare in the Age of

Marlborough, 1994, Sarpedon, New York, ISBN: 1-885119-14-13

Chandler, David, Marlborough as Military Commander,

1984, Spellmont, Staplehurst, Kent, UK, ISBN: 0-946771-12-X

Chartrand, Rene, Louis XIV's Army, Men-at-Arms #203,

1988, Osprey Press, London, ISBN: 0-85045-850-1

Churchill, Sir Winston S., Marlborough, His Life and Times, Vol 3.,

1938, reprint 1967,Sphere Books Ltd, London (sorry, published before the

ISBN system), this is a link to buy a used set. Since it seems to be

out of print, too, you can also read it online at Internet Archive.

Falkner, James, Marlborough's Battlefields, 2008, Pen

& Sword Books ISBN: 978-1-84415-632-0

Grant, Charles Stewart, From Pike to Shot, 1685-1720, 1986,

Wargames Research Group, ISBN 0904417395

Greiss, Thomas E., et. al., The Dawn of Modern Warfare, The West

Point Military History Series, 1984, Avery Publishing, ISBN: 0-89529-263-7

Hall, Robert and Iain Stanford and Yves Roumegoux, Uniforms and Flags of the Dutch Army and the Army of Liege, 1685-1715, 2013, Pike & Shot Society, ISBN 1902768523, CD-ROM from On Military Matters.

This source was also extremely diligent in describing uniforms, flags,

organization, tactical deployment, and the changing regimental names by

date for the Dutch and its mercenary forces.

Jorgensen, Christer, et.al., Fighting Techniques of the Early Modern

World, AD 155- AD 1763. 2005, St Martin's Press, New York, ISBN:

0-312-34819-3

Nosworthy, Brent, The Anatomy of Victory: Battle Tactics 1689-1763, 1990, Hippocrene Books, New York, ISBN: 0-87052-785-1

Wagner, Eduard, European Weapons & Warfare 1618-1648, 1979, Octopus Books, London, ISBN 0-7064-1072-6 While this book covers a generation or two before Oudenarde, it has a very informative section on the types and use of artillery throughout the 17th century, which our characters would have still employed in 1708. Military technology was not moving as fast in the early modern period as it would in the late modern, though, as Nosworthy explains, the introduction of the flint musket with bayonet replaced the old arquebus and pike of the 17th century and encouraged the introduction of fewer ranks in the infantry, something which the French were slow to adapt.

Online:

More

and more, when I research one of these battles online via Google, its

AI tries to offer help. But it has yet to be at all useful, and is

frequently wrong. So I use the following:

Kronoskaf https://kronoskaf.com/wss/index.ph title=1708-07-11_%E2%80%93_Battle_of_Oudenarde

Best site by far for the most reliable and comprehensive source for the War of

the Spanish Succession: armies, regiments, battles, personalities.

Wikipedia (obviously) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Oudenarde I'm sure this is the first place most people would go. But this particular article seems to rely heavily on Goslinga's Munchausen self-reporting of how he was the true hero of the battle.

British Battles Site https://www.britishbattles.com/war-of-the-spanish-succession/battle-of-oudenarde/

Mouillard, http://pfef.free.fr/Anc_Reg/Unif_Org/Mouillard/mouillard.htm for contemporary uniform and flag references on the French Army during the 18th century

Bacchus painting guide for uniform references https://www.baccus6mm.com/PaintingGuides/WSS/

The War Office, UK, for detailed information about Danish forces during the WSS

http://www.thewaroffice.co.uk/Blenheim/DanishUniforms1699-1720.pdf

Tacitus, https://www.tacitus.nu/english.html more detailed information on Danish, Prussian, Saxon, Holstein-Gottorp regiments during the WSS from Örjan Martinsson

Battlefield Anomalies, The Battle of Oudenarde https://battlefieldanomalies.com/18th-century-battles/the-battle-of-oudenarde/ Excellent photos of the site today, including how insignificant the barriers of the Marollebeek and Diepenbeek were.