19 April 1775

American Revolution

Colonials: around 500 militia mustering at Concord, rising to over 4,000 by the end of the day

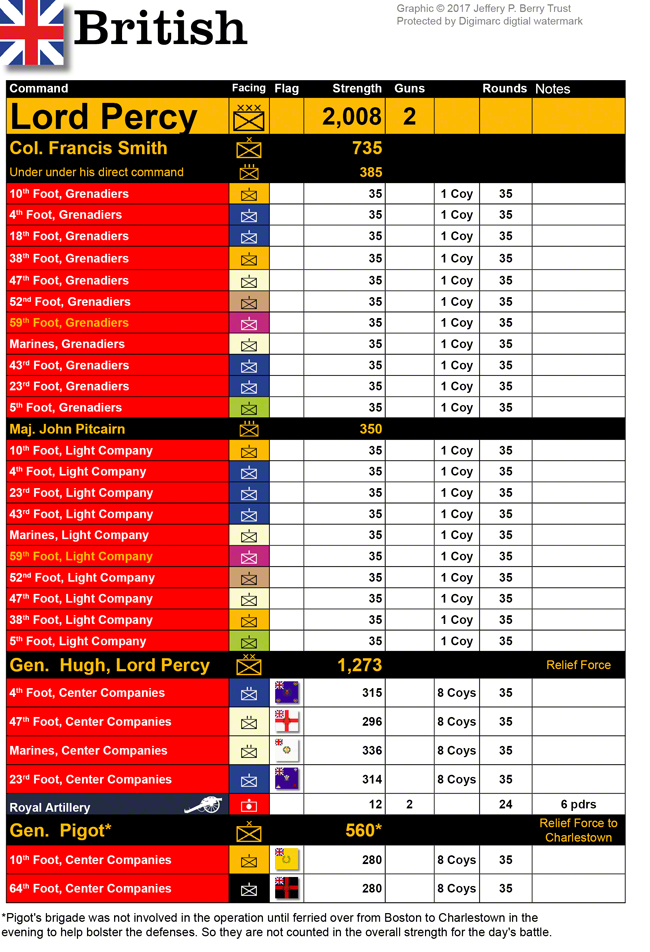

British: under Lt.Col. Francis Smith (later Gen. Hugh, Lord Percy), initially around 848 rising to about 2,121 by the afternoon, with two 6 pdr guns.

Location: 42° 28’8” N, 71° 21’ 2” W Concord, MA, United States

Weather: Mild temperatures. Visibility: clear. Wind: slight, out of the west. It was also black fly season, which can be very irritating to anyone who has experienced a New England spring.

First Light: 04:31 Sunrise: 05:00 Sunset: 18:35 End of Twilight: 19:04

Moonrise: 22:21 waning (83%) gibbous

All times UTC -5 (Romeo, Zulu -5, or EST)

(calculated from U.S. Naval Observatory from lat/long and date)

The Myth of the Embattled Farmer

But the opening battle of the American Revolution at Lexington and Concord wasn't a miracle. And as with so much else in an accepted historical and national narrative, it was slightly different than has been portrayed. As I hope to demonstrate in this article, most of the advantages of numbers, training, tactics, and combat effectiveness were on the side of those poor, embattled farmers, who, as they turned out, weren't so much yokels as well-drilled and seasoned combat veterans. Also the professional troops pitted against them were, for the most part, unseasoned, poorly trained, and led by ineffectual amateurs themselves. And, finally, that the events of that day weren't a spontaneous reaction to British aggression so much as a long-planned military operation carefully designed and provoked by American radicals with a political objective. As with some of my previous posts, the "obscure" part of this is in its departure from the popular story.

The First Shot was fired eleven years before

Lexington-Concord was no spontaneous thing. It started more than a decade before, in 1764, after Britain had "won" the Seven Years War and found itself in crippling debt. Parliament, under George III's sycophantic prime ministers (culminating in the thick-skulled Lord North), had the brilliant idea of taxing the American colonists for their own colonization. The rationale was that since they were these colonials who had benefited most from kicking the French out of North America, (but also |

| Lord North Who looks as out of touch as he was. |

Beginning with the Sugar Act (1764) ,then the Stamp Act (1765), the Townsend Acts (1767) the Tea Act (1773), and finally the completely counter-productive and bone-headed Coercive Acts (referred to by the Americans as "The Intolerable Acts"), Parliament started to impose not just crippling taxes on the Colonies, but did so without their consent, since no colonist could vote for Parliament or even stand for MP. These laws also began to take away even the local control of their own governments by dissolving colonial legislatures, firing locally elected officials and judges, denying Americans (at the time British subjects) basic rights, and, to add insult to injury, enforcing the monopoly on trade by the East India Company. It was the result of a bald-faced plutocracy. What is surprising is that the politicians in London were themselves so surprised by the rising resentment and open opposition to their benighted policies. Oppressors rarely have any empathy for those they are oppressing.

By 1770 the opposition in America to Crown policies and appointed officials had become so violent that the Prime Minister Lord North decided to pour gasoline (or, in his day, whale oil) on this fire he had started by sending troops to occupy Boston, the hotbed of resistance. Bostonians were widely known to be obnoxious by people on both sides of the Atlantic. You know how Red Sox fans can be. But stern measures would teach 'em. Like those always work.

To revolutionaries like Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Joseph Warren, Paul Revere, and John Adams, however, this stern lesson was a gift. On 5 March 1770, an ugly riot in Boston provoked seven of these hapless garrison troops (of the 14th and 29th Foot) to fire on and kill four patriots (or rabble, depending on which side you were standing on) who had been pelting them with rock-loaded snowballs. Instead of "teaching them," the military occupation only fueled the rebellion. When the seven soldiers who had been accused of murder were acquitted by a jury because they were only acting in self-defense (presided over by a Crown-appointed judge, but defended by John Adams, Sam's cousin), the resistance grew even stiffer. And Sam Adams grew happier. More acts of rebellion followed (e.g. the Boston Tea Party in 1773) and the Sons of Liberty party gradually built up an infrastructure of a "shadow" self-government and military organization.

|

| Thomas Gage painting by John Singleton Copley |

When this oppressive and reactionary legislation, among other things, completely shut down the port of Boston to all trade, Gage was left with a hopeless mess. Boston, for the British administration, became like the Green Zone in Baghdad after the 2003 Iraq War. It was full of resentful, unemployed merchants and longshoremen who hurled threats and insults at the occupying troops, who were, understandably, constantly on edge. Feeling the resentment around them, some Redcoats committed acts of violence on the Bostonians who taunted them or who they felt were cheating them (tarring and feathering was a popular torture technique employed by the British soldiers). And patriot Bostonians committed retaliatory acts on neighbors who showed sympathy for the British (disparaged as "Tories" in mistaken belief that this defunct political party was still running the much despised Parliament in London). It was not a vacation assignment to be stationed in Boston in 1774.

When he got there, in an attempt to show who was in charge, Gage began sending out regular expeditions of regiments into the Massachusetts countryside, both to demonstrate power and to exercise the troops. These Redcoat field trips became a pretty regular sight to the Colonials in the year before April 1775. They also gave the Colonials practice in building up a warning system, consisting of a network of riders who would fan out across the countryside, from town to town, alerting the militia. These militia would fall out and frequently observe the marching Redcoats from conspicuous ridges, showing their own armed presence as defiance. The Colonials would also tear up the planks of bridges on the way to impede the British, who, frequently, would just turn around and march back to Boston the way they had come. It was increasingly tense. And increasingly tedious.

The Minutemen

Besides the system of alert riders, the local Colonial government, the Provincial Congress, also established a Committee of Safety, who started to build up a professional military force in December of 1774. Militias had always been a part of colonial life since early in the 1600s. The institution had been imported from England where self-defense militias had existed for centuries. But starting at the end of 1774, a new type of self-defense establishment was created within the traditional militia, the Minutemen.While militias were composed of all able-bodied men in any given town, they had only engaged in sporadic drill, mostly just meeting once a year to share rum and stories. By act of the Provincial Congress at the end of '74, however, one third of the militia, designated Minutemen, were specifically required to meet three to five times per week for intense military training. Like modern volunteer firemen, they were required to fall in at a minute's notice, literally, on each town's common, armed and loaded with at least 36 rounds. Several Minuteman companies had acquired bayonets (that terror weapon of professional armies) and artillery. Spies (and every American was a spy during this period) would go into Boston to observe the Redcoats drilling on the Common, then bring back their notes to teach their own companies. Many civilians-turned-officers, like William Heath, Joseph Warren, and bookseller Henry Knox, steeped themselves in historical military literature and contemporary manuals and passed that knowledge on to their own companies. It has been noted by tradition that the officers of this first Colonial Army were amateurs. I have to point out, though, that in the age before Sandhurst and Westpoint, all officers on both sides were technically amateurs. British officers were usually the sons of wealthy aristocrats who bought their commissions, and only those who took an avid interest in their profession other than its social status would read up on it. As we'll see in this battle, that glaring amateurism would cost the British dearly.

|

| Romanticized engraving of an alarm rider calling out the militia. The little girl and barking dog are a nice homey touch. |

The other aspect of the Minutemen that made them a formidable force was that a large percentage of their officers and personnel were combat veterans of the French and Indian War, which had ended just a dozen years before (put into context, just half the time between the First and Second World Wars). Not only did these men know how to fight, they were masters of the kind of self-reliant, light infantry tactics that had dominated that war. By contrast, almost none of the young rank-and-file and few of the officers in the British regiments in Boston had ever seen actual combat. Most, in fact, had been previously employed in Ireland to police that country, where, one can only imagine, they were just as hated. And all of the British privates were impressed into service against their will, poorly paid, beaten savagely for minor infractions, and didn't want to be in this alien city where everybody glared at them. Not the most highly motivated fighting force.

Though the spring of 1775 came early, and plowing and sowing had started, from December to April, many of the Minutemen were not so encumbered by their farming duties during this season that they couldn't devote much of their time to training. They were all so motivated by the outrages of Parliamentary Acts and British oppression that they gladly met as often as possible to practice their combat skills.

In the four months from the creation of the Minutemen in late '74 to the fateful march to Concord, the Colonials had created a highly effective army. Estimates by contemporaries and histories range from 14,000 to as many as 30,000 in Massachusetts alone. This against only a little more than 4,000 British troops holed up in Boston.

Yet another "field trip"

From 7 April '75, General Gage had been getting some juicy intelligence from his spy in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Dr. Benjamin Church, that that assembly was meeting "illegally" in the temporary "capitol" of Concord and that they were in discord with each other. He also learned that the Massachusetts Committee of Safety had created a huge magazine of guns, ammunition, and military stores in Concord. So he decided it was time for another field trip for the troops to take a day hike. As with previous sallies, this one was supposed to be secret; military movement being highly classified, of course. (Not like today where, apparently, senior defense department officials can discuss top secret tactical operations on chat rooms from their iPhones.)On 15 April Gage sent orders to each of his regiments to excuse their grenadier and flanker (light) companies from further duties for the next few days as he had a special mission in mind for them. Early on 18 April, he got detailed intelligence (from Church?) about exactly where in Concord all of the arms and military stores were hidden. It was time to act, he thought. So he ordered all the sequestered flanker and grenadier companies to assemble on Boston Common to embark on their special mission at 2100 that night, and to take no baggage and only 36 rounds each. They were going to need to move fast and light. And no fighting was anticipated (how often has that assumption come to rear its ugly head in history?).

So that evening the 21 assigned companies started to assemble on the Boston Common. Boats had been run up on the shore of the Charles River to ferry them across to the Cambridge side (see map above). Nobody in the force except the commander, Lt Col. Francis Smith, knew where they were headed. There had been so many of these expeditions before. But, of course, virtually all of civilian Boston knew. Since the cryptic order to the flanker companies three days before, it was hard to keep a secret that something was up. Seven hundred soldiers were bound to blab their hunches and rumors to each other and their girlfriends. Also, the Sons of Liberty also had their own spies high up in Gage's administration. Joseph Warren was one. He was not only an old and valued friend of the Gages' (he had been their family's doctor for years), he was also known to be president of the illegal Provincial Committee of Safety. Even Gen. Gage knew this as he kept having him over to the house for convivial sherry and conversation. But apparently Gage didn't see the risk. They were gentlemen, after all.

It is important to remember that, at this point, Britain and its Colonies were not yet at war. There wasn't even, at least on the British side, a rumor of war. All of the Colonists' military preparations in the countryside had, ironically, been dismissed, even though the purpose of the expedition was to seize military contraband. Gage was assuming this would just be another stroll in the countryside like all the rest, with some demonstrations by the provincials signifying nothing. So it wasn't as if, in having Warren over for dinner, Gage and his affable American wife, Margaret, were colluding with the "enemy". There was no enemy yet. Gage felt that sherry and dinner table diplomacy could go much further in damping down rebellion than military force. And he and Margaret very much enjoyed Dr. Warren's charming company.

Nevertheless, at 2100, all of the Redcoats tallied off for the mission were lined up and ready to go at the embarkation point. But the expedition's commander, Lt. Col. Smith, had yet to show up. Since the Navy's boats were already lined up on the beach, the company commanders began to get their men into them. There they waited, sitting on the gunwales, until their leader showed up about 2230, an hour-and-a-half late, and gave the order to shove off.

Unfortunately cracker-jack British staff work again showed its quality and there weren't enough boats to take all 700 across to the Cambridge shore at in one crossing. So precious time was wasted in dropping off the first bunch, rowing back, and collecting the next installment. It wasn't until three hours after the "go order", sometime after midnight, that the whole expedition was deposited on the western shore. Or almost. By this time the tide had ebbed out and the men were standing around in the tidal muck, waiting for their supplies to be ferried over. They waited another two hours.

The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. Oh, and one other.

There were two ways out of Boston then. One was to be ferried over the water (as Gage and Smith chose)--"by sea". The other was to march down the "Neck", a causeway connecting Boston, which was otherwise an island, to the mainland--"by land". (See strategic map above.) Normally previous excursions took this land route since it didn't require the cooperation of the Royal Navy and it didn't depend on the tides. But it was the longer way around. Also, it was reasoned that the provincials would get wind of this route and dismantle the strategic bridge over the Charles River at Cambridge.Joseph Warren had told Paul Revere and William Dawes to be ready to cross over to Charlestown and start spreading the alert when it was known when and where the British expedition would start. Agents were positioned in the Old North Church in Boston to light one lantern if the march was to be down through the "Neck" (by land) and two if across the Charles (by sea). This would alert watchers on the Charlestown and Cambridge shores to get ready with fast horses for the alarm riders and to start tearing up the bridge at Cambridge. This system had been practiced several times before during similar Redcoat forays and the Colonials had it down. When Warren was convinced the British were about to embark on the longboats, he had the two lanterns lit and sent Revere out across the water to Charlestown. Revere had to sneak with bated breath and muffled oars right under the bowsprit of the man-of-war, HMS Somerset, to get to the Charlestown wharf, where he was met by friends with a fast horse. Fortunately, he left just before the moonrise so he was able to cross in darkness. Dawes took the "land route" past the "Neck". He brazenly joined a British patrol also heading out, convincing their officers he was off to visit a "mistress" in Roxbury (or something...anyway, they all had a big laugh and invited him along in the spirit of fellowship).

Then began the "Midnight Ride" immortalized by Longfellow in 1860. Revere galloped through Medford and Menotomy, eluding British officers sent out to intercept any alarm riders, alerting the local Minuteman units along the way (word had spread that day so they were already on high alert). He galloped into Lexington about midnight, while Smith's grenadiers were standing around back in the tidal muck of Cambridge waiting for their packed lunches to arrive. As Revere passed, more riders radiated out and passed the word all up and down eastern Massachusetts. Dawes rode through Roxbury, Brookline and Cambridge and joined his friend Revere in Lexington. (See larger map above for reference.)

|

| Another romanticized engraving of Revere (or maybe it was Dawes) rousing the countryside and, of course, the obligatory cute dog. |

So the two got out. Eventually. Not right then, evidently. Some time was spent retrieving all of Adam's papers, getting him a carriage (he hated riding a horse), and persuading Hancock, who was strapping on his expensive sword, not to stay and lead the charge. Revere and Dawes left them to it and continued west down the Concord road to wake up the militia there. They were joined by a Concord doctor, Samuel Prescott, who happened to be going home that way anyway after having a date with his girlfriend in Lexington and thought it was an exciting adventure.

Halfway down the road to Concord, though, all three men were accosted by several mounted British officers whom Gage had sent out the day before to watch the roads and arrest any alarm riders. One of the officers seized Revere's reins, but Prescott and Dawes galloped off across the moonlit fields (Prescott knew this country well, since it was his own neighborhood) and the senior officer of the picket group, Major Edward Mitchell, was forced to let them get away. Revere was also later let go since he had--at least technically--broken no law--it wasn't illegal to take a midnight ride--and Mitchell didn't have a reason to hold him after the main column marched through Lexington. At this point, the British were still respecting the civil rights of the Colonists, who were, after all, still British subjects. Remember, there was no war yet.

Alrighty then! Now we've got ourselves a war!

Smith's column, once everybody got over from Boston to the left bank of the Charles, took awhile to get itself organized. This wasn't an integrated regiment, after all. It was a hodgepodge of companies from all the garrison regiments in Boston. They were not used to working together, and many had strange officers assigned to them. Smith insisted that they wait until supplies of food be ferried over. When these showed up, many of the men threw them aside thinking they would be back that evening anyway and didn't want to carry extra weight on the march.It wasn't until after 0200 that they all got underway to start schlurping out of the mucky tideland. They marched through Menotomy about 0300 (which a British soldier referred to as "Anatomy" in his letters home. I'm sure other wits called it "Monotony". The city fathers apparently grew tired of this derision and changed the name to Arlington in 1867). They all just started getting to the Lexington Common, a little under five miles further on, at about sunrise, or 0500. On the way Smith had been met by the agitated Maj. Mitchell, galloping in a tizzy back from Lexington. Mitchell breathlessly reported that Revere had bragged to him that the entire countryside was up in arms. Indeed, in the pre-dawn light the troops could see furtive figures running westward. Mitchell had also claimed that he and his patrol had "been forced to gallop for our lives" from Lexington. A lie, of course; Mitchell was a histrionic character. Without any solid intelligence (in both senses of that word) he told Smith that as many as 2,000 militia were waiting for them at Lexington

Smith only had 700 men with him. The night before, as Gage handed over his carefully written orders to Smith, he told him he was only sending him out with a small force, something less than a brigade, because he wanted him to move fast, get the job done, and get back before sunset the next day. He was also explicit in how he was to respect the rights of the inhabitants and not inflame them, or their houses. But if he ran into resistance, he told Smith to not hesitate to send for help, that he would keep a full brigade on alert and ready to go. Alarmed by what the hysterical Mitchell was telling him, Smith concluded he was going to need help. So even before he got to Lexington, he sent a message back to Boston that, yes, he was going to need reinforcements. And for them to come quick.

| |

| Lt. Col. Francis Smith in his younger days, 1763 |

What they actually saw were only 77 men of Capt. John Parker's Lexington Minuteman company, lined up in a line of two ranks on the far right side of the green, as far away from the Concord road as possible.

Five hours earlier, when Revere and Dawes had galloped into town to wake up Adams and Hancock and the militia, Parker sent out riders to the surrounding farms for all the Minutemen to assemble on Lexington Common. About 0100, after taking the roll, Parker dismissed the men who showed up to wait at Buckman's Tavern (see map below), ready to fall in as soon as the Redcoats showed themselves down the Menotomy road. There they waited, some coming and going, for four hours. It was probably a tense night. Parker knew that the march from Cambridge to Lexington (about 9 miles) should at most have taken about three hours, and Revere's report said that the British were supposed to have crossed the Charles at 2100 the previous night (remember, they didn't end up starting the march until 0200). Parker kept sending out scouts, and, ominously, none returned. He paced outside of Buckman's all night, peering down the moonlit road toward Cambridge.

At about 0430 one of Parker's scouts had finally galloped in breathlessly to report that the Regulars were only a half mile down the road. The captain had his teenage drummer, William Diamond, beat to quarters, calling everybody out of the tavern (and their adjoining homes) to fall in again. He first lined them up next to the Concord road on the south side of the green. But he had standing orders from the Committee of Safety not to interfere with the British and not to fire unless fired upon first. So he then prudently marched his company back across the green to line up on the north corner, showing themselves in defiance but not in obstruction. He reiterated his order for no one to fire. At this point this still resembled a modern civil protest confronting the cops. For the previous year the provincials had been used to these peaceful demonstrations of resolve, and they usually ended with the British backing away. So Parker assumed this would be the same thing.

Major Mitchell, the one who had shrilly warned Smith of the countryside in arms, was riding with the leading companies of Regulars (4th and 10th Regiments of Foot). When he saw the line of Minutemen filing off to the right, he became instantly incensed and shouted, "Damn them! We will have them!" (the equivalent of dropping an "F" bomb in the 18th century). On his own authority, he took charge of those leading companies and led them around the right of the Meeting House to cut the rascals off. About seventy yards from Parker's company, who had halted to face them, Mitchell ordered the two Regular companies to deploy and "lock on" (get ready to fire). These Redcoats were also surrounded by his entourage of other freelance officers, all riding around shouting vulgar epithets at the militia., and contradictory orders at the Regulars. The British rank and file themselves, after having endured months of verbal abuse from these Colonials, were itching to give it back, in leaden form. Everybody was on edge.

In a later deposition, Capt. Parker swore that he had already ordered his Minuteman company to disperse as soon as the Redcoats arrived at the Common. He also asserted that he had told them repeatedly and definitely not to fire. Many already had started to leave the ranks and walk off as ordered. He said that his original intent in lining up was to show resolve and not to challenge the British to battle, which, given the overwhelming disparity of numbers, would have been suicidal. Major Mitchell, for his part, said he believed the militia were heading for some stone walls to take cover and he was trying to stop them. This wild-eyed character probably did more than any other single person to get the whole war started.

Major John Pitcairn, of the Marines, who, as Smith's second in command and had formal authority over all the flank companies in the van, was some way back in the column and had not anticipated that there would be any freelance adventuring off of the main line of march (the road to Concord). They weren't even supposed to stop in Lexington (contrary to what Revere had told Adams and Hancock about the British coming to arrest them).

So when Pitcairn arrived on the scene, he rode to the left of the Meeting House (see model above) and saw his lead companies already deploying and going after the militia. He galloped over to see what was going on. A bunch of confusing orders were being shouted by the various mounted officers who had come along for the ride, none of whom knew the men. And the men didn't know them. Pitcairn himself yelled out conflicting orders to both his own men to surround and disarm the militia and keep them from dispersing, and at the militia to alternately drop their weapons, don't move, and disperse. ("Well, which is it you want us to do, young fella?") Everything was happening so fast and, consequently, there are no reliable accounts for exactly what came next. Some witnesses said they thought they heard the order to fire (from somebody)...or maybe it was "Don't FIRE!" Other witnesses swore that the British definitely started to fire first. Others claim that some drunk staggering out of Buckman's Tavern accidentally fired. Loyalists swore that it was Sam Adams who shouted "Fire!" from the sidelines to get the incident he needed (just as he was supposed to have done at the Boston Massacre five years before). But he also had an alibi as he had already left town at least an hour before. He did say, after the incident, "Oh, what a glorious morning!" He had, for years, been trying to start this war. But he wasn't at Lexington at sunrise.

- I have an aside

here that is pertinent to this story of who may have fired first.

Several years ago I witnessed a standoff between an armed bank robbery

suspect and about a dozen police. I was watching from a second story

window to the street below where the suspect had crashed his car and was

now surrounded by the cops. Everyone had their guns out and everyone

was yelling. As with the hodgepodge of British flanker companies at

Lexington, the police were from a variety of departments whom the

robber had led on a wild goose chase through several municipalities until he

ran into a parked car on the street below my office. He got out of his car and stood behind the open door,

holding a gun to his own head, and threatened to kill himself if the

cops didn't back off and negotiate with him. All of the police and

sheriff's deputies were screaming at him to "Put the gun

down!", "Don't move!", "Get on the ground!", "Freeze!"...in other

words, uncoordinated, conflicting orders.

After about a minute of all of this yelling, one of the cops' guns went off. Instantly, in chain reaction, all the cops' guns went off. The robber went down in a hail of bullets. He had never fired his gun or even pointed it at anybody but his own head. On the news that evening, the official police spokesman claimed that the suspect fired first (he didn't, in fact he never even threatened the police themselves) and that they, tragically, had to take him down. Which was a lie. It was just one jumpy, scared human being, pumped with adrenaline, unintentionally squeezing a trigger. I and everyone in our office who had witnessed it were interviewed separately by Police Internal Affairs right after the incident and reported what we had seen, but to my knowledge, no action was taken and the truth was never reported in the media.

As I was writing up this article, I remembered this personal incident in thinking about what happened at Lexington that morning over two centuries before and how my country got started. Like all history, the facts were curated to fit the desired narrative.

At any rate, whoever fired first on the Common that morning, once there was a pop, all of the leading British companies started firing independently and charging at the militia. Supposedly disciplined, professional soldiers became an enraged mob. One of the Minutemen standing next to Capt. Parker, Jonathan Harrington, remarked that the Redcoats must be firing blanks to scare them. But men around him started getting hit and he exclaimed in horror, "They're firing ball!" Parker's men, for their part, immediately started to break and run, getting off a shot or two themselves. As Harrington himself was running back toward his house at the edge of the common, he was shot in the back. He crawled to his front door on the north side of the green, where he died in his wife's arms.

Amos Doolittle's contemporary engraving of the fight at Lexington, illustrating the Colonists' story that the British fired unprovoked.

|

The British soldiers now went berserk. They chased after the fleeing militia, bayoneting some and shooting others, like Jonathan Harrington, in the back. There was no attempt to arrest anyone or take prisoners. Wounded men were bayoneted multiple times to make sure they were dead, sometimes even after they were already dead. Other companies marching on to the Common also broke ranks and joined in the riot. Neither Mitchell, Pitcairn, nor any of the officers seemed to be able to stop the mayhem for several minutes. Pitcairn later testified that he had been frantically slashing his sword downward as a "cease fire" command but was unheeded. It wasn't until Col. Smith arrived on the scene and he had the presence of mind to grab a drummer to beat the recall that the rioting soldiers stopped and fell back into rank.

The British killed eight militia and wounded ten, including one Prince Estabrook, the first African-American to become a casualty in the fight for independence (if you don't count Crispus Attucks at the Boston Massacre five years before the war began). Estabrook was a slave, who had to have been given permission by his "owner" to volunteer as a Minuteman.

- And yes, there were slaves in

Massachusetts then, as there were in all thirteen American Colonies. In

fact, at the time, almost one in four Americans were slaves.Which

prompted Samuel Johnson's cynical quip, "How is it we hear the loudest

yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?"

The story here has a personal happy ending for Estabrook in that he recovered from his wound, went on to fight with the Continental Army throughout the war, and died a free man, distinguished patriot, and honored veteran sixty years later, at the age of ninety. Unfortunately his own sacrifice and service were not enough to win the liberty of 500,000 of his fellow slaves at the end of the war.

Capt. Parker and his survivors managed to escape and rally just north of town. They were joined by others of the Lexington militia who had not been present and would later join in the fight that afternoon as Smith's column retreated that way again. This was now war and all civility was off.

While the militia suffered 18 casualties in this opening "battle", or almost a quarter of those present, the British got off relatively lightly, with one slightly wounded among the British (shot in the right shoulder from the direction of Buckman's Tavern), and Maj. Pitcairn's horse also slightly wounded (but evidently fit enough to carry him on to Concord and throw him later that day). But the real casualty was peace. Because of Pitcairn's and the other officers' incompetence, any chance for avoiding all out war this day was itself shot dead. For his part, Pitcairn, a Marine, blamed the infantry. Marines would never have been so undisciplined, he asserted. And apparently, the two Marine companies with the column did not participate in the massacre.

Onward to Concord

After Col. Smith regained control of his unruly troops and everybody had cooled down, he got them marching again toward the day's official objective, Concord, six miles further on.

- You've noticed I've stopped converting to metric by this time in the text. You can use a handy app on your smartphone to do that, or do it in your head-: 1 yd = 0.9144 meters. Nobody was using the metric system in 1775 anyway. Especially in British America. And many contemporaries were using "rods"--5.03 meters--to describe distances. I won't do that. Or use "leagues" (5,556 m) or "furlongs" (201.168 m) or "paces"(0.762 m).

As the British marched, several companies of Minutemen from Concord were marching in the opposite direction, toward Lexington. A little out of town, these ran into survivors from Parker's men running toward Concord, and were told of the massacre on Lexington green. The Concord men stopped, waited for the head of the British column to come into view, then turned and marched ahead of it back to Concord, the two forces so close that their fifers and drummers joined in the same song (probably "Yankee Doodle Dandy" which the British played as derision and the Patriots picked up sarcastically). The militia kept on through town, first taking up an observation position on a ridge on the east side of the North Bridge, and then moving across the river to park themselves on a hill near John Buttrick's farm (see map below).

Smith's column arrived in downtown Concord a little after 0800. The place was practically deserted, having long since been alerted to the coming of the Redcoats, with many of the townfolk having fled to the woods behind Buttrick's farm on the far side of the river. Smith sent seven of his light companies under Capt. Lawrence Parsons (10th Foot) north to secure the North Bridge over the Concord River and to search for hidden contraband across the river. Gage's intelligence had identified a cache of it at Barrett's farm there. He sent three more companies under Capt. Mundy Pole (also of the 10th, Smith's own regiment) to guard the South Bridge. The rest of his command, eleven companies of grenadiers, he had fan out over the town to scour for military stores.

Amos Doolittle's engraving of the raid on Concord from the same series. Maj. Pitcairn and Lt Col. Smith (not exact likenesses) are in the foreground on Cemetery Hill, looking north toward the North Bridge. Doolittle was not a professionally trained artist, obviously.

|

The first thing the grenadiers did was chop down and burn the offensive "Liberty Pole" mounted on a hill above the town. This must have made them feel good, especially after all the insult they had endured in Boston for months. Then, not too systematically, they knocked on doors and asked permission of the residents who remained if they could search their houses and basements and barns for contraband. Several of these people simply said, "No" or "No we don't have any of that stuff. Go away." And the Redcoats obliged. The British officers and NCO's chastened and embarrassed by what the "light companies" had done in Lexington, were scrupulous in respecting property rights. In this sense, the "raid" was a farce. Some barrels of flour were found and dumped in the Concord Mill Pond, as well as some bullets and a couple of rusty gun barrels. The officers told the men to put the bullets in their pockets and drop them randomly on the way back to Boston so they couldn't be fished out of the Concord Mill Pond (they didn't, they just dumped them in the pond, too, where they were fished out by the Colonials). And a couple of gun carriages and some other "military stores" were piled up and set on fire on the town common and near the South Bridge. For the most part, the Concordians had done a good job of dispersing all the arsenal that had been kept there. And even the barrels of flour were retrieved later; interestingly, the water that seeped into the barrels turned the outer layer into paste, which acted a sealant and preserved most of the flour within.

But to the British soldiers, who had not realized the dramatic change of events that they had initiated at Lexington that morning, there was still no war on. They respected property rights. They weren't breaking into the houses and barns. These were fellow Englishmen, after all. So they behaved as they would have in a little town in England. At one point, a spark from the burning military contraband on the village green blew over and lit the courthouse on fire. An old woman hurried over to the lounging grenadiers and urged them to put the fire out and after she berated them for their indolence, they meekly obeyed her and extinguished it. At another location, a group of officers were taking their ease, sitting on chairs in the front yard of one of the houses. They prevailed upon the good woman of the house to bring them some cider; they had been marching for hours and were hot and thirsty. And she obliged. They insisted that she accept payment, which she did, reluctantly, calling it "blood money", but she still took it. It was hardly a raid of Cossacks.

But they just stood (or sat) there, watching the Redcoats below them. Barrett had made it clear (as had Parker in Lexington) that no one was to fire first. They were there just to show force and nothing more. Behind them in the woods, many of their families and neighbors had gathered to escape the British and were watching apprehensively. By 1000 rumor had spread to Barrett's men of the atrocity at Lexington at dawn that morning. Many had asked that common question that morning, "Were they using ball?" Meaning, had they used live ammunition?

View SSE of North Bridge from Barrett's position on the hill. Image from Googlemaps Street View.

The Minutemen of Barrett's regiment, however, had quite a few actual combat veterans among them, men who had served with the British Army during the previous war and who knew what they were doing. They had also been diligently drilling for months prior to this. They were ready.

Barrett sneaked back through the woods to rejoin his regiment about 1030. At that point someone pointed out a disturbing sight. There was smoke rising from Concord to the south. Joseph Hosmer, a captain of one of the Minuteman companies loudly shouted to Barrett but for everyone to hear, "Will you let them burn the town down?" Everyone shouted "NO!" This was a democratic military culture, remember.

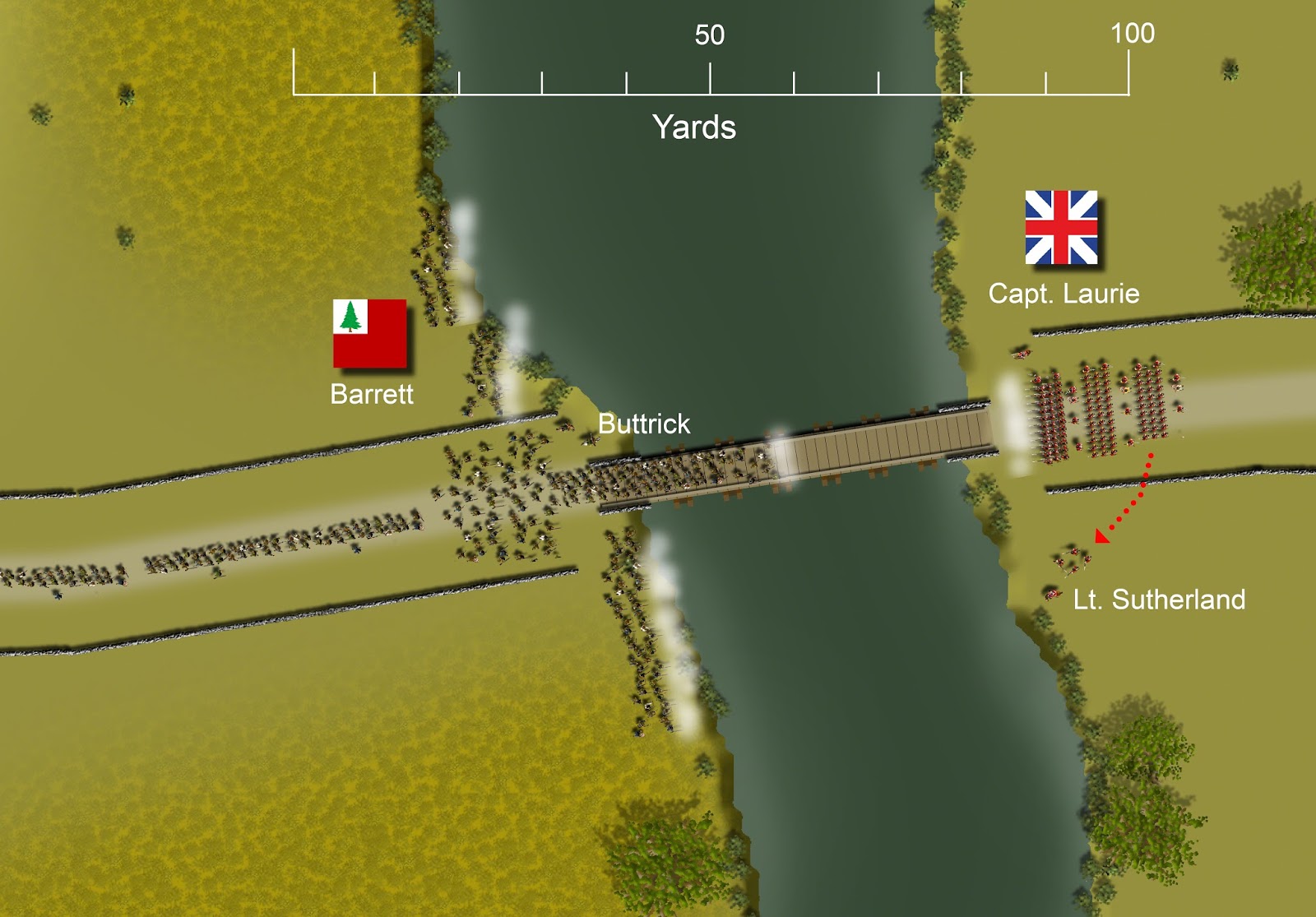

The Fight at North Bridge

The militia regiment marched rapidly in column down the flank of the hill and followed a path between the river and some swampy ground to the west end of the North Bridge. The two isolated companies observing Barrett, of the 4th and 10th, did not hang around to see what would happen. They scrambled down the hill and join Laurie in front of the bridge. Watching this movement from his exposed position, Capt. Laurie thought it prudent, given the fact that he was overwhelmingly outnumbered, to withdraw everybody over the bridge and defend it from the other side, where, presumably, he would have the advantage of blocking a defile. His idea was that he could stack the three companies in column and that as each platoon fired, it could fall back to reload while the next platoon fired, and so on. It was a venerable fire system from an earlier age of wheel locks. He had practiced this back in Boston with his own company of the 43rd Foot as "street fighting".

View of the North Bridge from the British side. You can see how close the opposite bank was and how vulnerable Laurie's men would have been to aimed musketry lining that bank. (panorama by Jeff Berry, all rights reserved. Image protected by Digimarc embedded watermark)

|

The 500 Minutemen, meanwhile, were rapidly spreading out across the opposite bank of the river on either side of the bridgehead, taking up firing positions. Laurie later commented that he was impressed with the sharpness of their military bearing and discipline, and how quickly they deployed into a line. He also noted, with alarm, that some of the militia had bayonets, a weapon that was supposed to be restricted only to Regulars.

Laurie had just got his three companies over the bridge as the lead elements of the militia regiment got to the western side. He had ordered his men to tear up the planks, but they didn't have time, (or crowbars to pry up the nails). As the three British companies stacked up in echelon (see the digital model below), the lead Minuteman company, Isaac Davis' from Acton, were already thundering across. Davis was a ferocious fighter. As a gunsmith he had personally armed his company, including with bayonets. So it was natural for him to lead the charge.

As at Lexington there was some dispute about who fired the first shot here. Though with the Colonials running across the bridge with lowered bayonets, that seems to be moot. The British were plenty scared. Maj. Buttrick, directing the militia's charge, called out for the Redcoats struggling to stop trying to pry up the planks to leave them alone. Laurie ordered his leading company, from the 4th Foot, to open fire. Both Capt. Davis and a man named Abner Hosmer were killed instantly and three others wounded. On the west bank, Barrett heard Buttrick exclaim, "My God! They're firing ball! Fire! For God's sake. Fire!" And all of the companies lined on the bank on either side of the bridge opened up on the packed Redcoats.

Below a model of the action at North Bridge. You can see by this how the flanks of the deep British formation were exposed to enfilading fire from the opposite bank of the river, 60-70 yards away.

At a range of under 70 yards the Colonial's musketry was devastating. In the space of a minute they managed to hit eleven (four of the eight officers and eight enlisted men) killing two of them. The Minutemen's target practice over the preceding months had paid off. They were firing individually, taking their aim and time. Later the British would complain that they seemed to be deliberately targeting officers. They were right. In fact, for the rest of the day, British officers took far more casualties than the rank and file as a proportion to their numbers. This was also considered uncivilized in the polite manners of Enlightenment combat.

Lt. William Sutherland, one of the freelance officers who had come along on the expedition on his own (actually against Smith's advice), had joined Laurie's ad hoc command. He saw that that captain's "street fighting" formation was useless on this country lane and that the provincials lining the opposite bank were enfilading both of the their flanks. On his own initiative he tried to get the rear company (from the 43rd Foot) to follow him over a wall and return the flanking fire from the provincials. Nobody knew who this officer was and only three or four men followed him. All were immediately shot down, including Sutherland, who was hit in the arm. He turned and ran, leaving behind the four brave men who had followed him. So much for following orders from somebody you don't know.

The light company of the 4th, at the head of the "street fighting" column that Laurie had set up, fired off their single volley and, according to plan, started to file back right and left to either side of the column and reload in the rear, and to allow the next company (from the 10th Foot) to step up next and deliver its volley. However, the 4th's opening volley, while taking down some provincials, apparently did nothing to stop their momentum across the bridge. And the hundreds of militia lining the opposite bank, were hammering hundreds of rounds into the flanks of the Redcoats; officers and men were falling at an alarming rate. The other two British companies, mistaking the retrograde movement of the men of the 4th Foot for a retreat, all broke and ran themselves, followed by the survivors among the eight officers who could walk (including Lt. Sutherland).

The Minutemen, infuriated by being fired on, swarmed across the bridge. As they did, a sociopathic teenager named Ammi White happened across one of the poor Redcoats who had followed Sutherland on his aborted flank adventure and been wounded for his efforts. White took out a tomahawk and proceeded to hack into the man's skull. Reverend William Emerson (Ralph Waldo's grandfather, living next door in the Old Manse) witnessed this barbarity and it disturbed him for the rest of his life. Horribly and incredibly, White left the mutilated soldier still alive. Emerson tried to do what he could but it took the poor soldier, probably not much more than a teenager himself, over an hour to die in agony. This incident was witnessed not only by Emerson, but by the fleeing Redcoats, and by Capt. Parsons' four companies as they returned this way an hour later. News of the atrocity took almost no time to spread through the British ranks, going rapidly viral two-and-a-quarter centuries before Facebook. Their former feelings of civility toward the provincials vanished. These people were no longer fellow Englishmen; they were now the enemy. And a savage enemy. They passed on the story as a "scalping", with all that that implied.

View southeast from the bridge. In the distance is the Old Manse, recently built home of the Reverend Emerson (Ralph Waldo's grandfather). In the foreground is the sad and lonely grave of the poor, unknown British soldier who was hacked to death by the sociopath, Ammi White.

|

Some minutes before, when Capt. Laurie first saw the hordes of Colonials, armed with bayonets, filing down the hill toward the bridge, he had sent a messenger back to Col. Smith to send up reinforcements. Smith, watching from Cemetery Hill in Concord center, anticipated him and led three grenadier companies from town up toward the bridge, meeting the fleeing light infantry halfway. Laurie's retreating men rallied behind the grenadiers. Buttrick's men, seeing the fresh line of Regulars (these in bearskins), stopped and fanned out up on the ridge above the road, taking cover behind a stone wall. Col. Barrett told Buttrick to hold this position and he led the half of his regiment that hadn't crossed back up to the hill on the west bank to watch for the return of Parsons' Redcoats that had raided his farm.

Time to go.

For the British, at least, the immediate crisis seemed to be stabilized. Smith realized the odds against him were mounting as more and more militia companies were arriving from all quarters. He sent for Capt. Pole to pull his three companies back from the South Bridge. But he hadn't heard yet from Parsons and his four companies, who hadn't returned from their expedition to Barrett's farm. He couldn't leave them behind. He was also looking anxiously eastward. He had sent his plea to Gage for reinforcements over eight hours ago. They had had more than enough time to march the sixteen miles to Concord. They should be arriving any minute.

In the meantime, he ordered all his remaining companies to finish what they were doing in the contraband burning business and fall in for the march back to Boston.

Finally, about noon, Capt. Parsons returned, crossing the North Bridge unmolested. He noticed the militia up on the hill to his left, and as he crossed his men came across the British dead and wounded, including the dying, anonymous young soldier who had been "scalped" by White. But he moved down to town without any other incident.

Shortly after this Col. Barrett had collected four more Minuteman companies from Action and crossed the North Bridge to join Buttrick, still hunkered down on the ridge behind a wall. More Minuteman companies from Framingham and Sudbury had also arrived from the southwest. And several companies from Bedford, Lincoln, Groton, and elsewhere were showing up east of town (see map below). By noon the Colonials had surrounded Concord with over a thousand men and outnumbered Smith's 700. It was time for the British to pack up.

Smith's companies fell into route order, a column of threes. Deploying his light companies in skirmish formation on his right and left flanks, Smith started to march back down the Concord-Lexington road. Parsons' seven flanker companies walked along the steep ridge to the north of the road. To their left they could see hundreds of militia paralleling their march, racing them to the bridge at Merriam's corner.

It was at this choke point that the militia who had accumulated there began taking shots at the packed Redcoats on the road. Crouching down and steadying their muskets across logs and stone walls, the provincials' experienced marksmanship started hitting several Redcoats. They were using the ambush tactics they had learned during the French and Indian War, and from generations of fighting Native American tribes, taking their time to aim carefully. After the lethal events at Lexington and the North Bridge, they were out to kill now. The British despised these skulking tactics as uncivilized and despicable, even though they had appreciated them when they required the Colonial militia to help them kick the French out of North America. Now that they were being used against them, it seemed unfair. Many officers complained that the rebels wouldn't stand up and fight like men.

- This reminds me of an old Bill Cosby bit (from when he was young and funny and hadn't yet become another toxic, old celebrity). He described the American Revolution as if it were a football game and the two sides got together for the pre-game coin toss. The American team wins the toss and the umpire announces, "The Americans say they get to hide, wear any color clothes they want to, and shoot from behind rocks and trees, while the British team has to wear red and march in a straight line."

Sorry, I do get sidetracked.

Eventually, after taking several more casualties, particularly among the officers, the British all finally got over the bridge and onto the road to Lexington, the Marines taking up the rear guard.

But their ordeal had just begun. All along the next five miles, militia were lying in wait, harassing the increasingly disordered Redcoats. The British light companies spread out to the flanks once more where they could, but whenever they did, they seemed to take more casualties than they inflicted. Their job was to push the ambushing provincials away from the road and the main body, but this was getting increasingly difficult to do. No sooner than they chased one group away than another, fresh batch would be lying in wait behind the next wall, barn, or clump of trees. Stragglers from the British column were being killed (if they resisted) or rounded up. The grenadiers on the road itself were wasting their ammunition by just firing away at the smoke and woods, usually too high, as if the noise itself would scare away their tormentors.

The Bloody Angle

Sometimes the terrain and a bend in the road would be particularly difficult to negotiate. At one spot, called, subsequently named The Bloody Angle at the National Park dedicated to this event, the road bent to the left for about 500 yards and then right, and the woods came right down to the edge on one side, with a steep slope to boggy ground on the other. Here several hundred militia and Minutemen, who had been racing ahead of the struggling column, had crowded right down to the edge of the woods and the British could not get on the flanks to protect the column, since they would get lost in the woods or trapped in the marsh. Fortunately, the British were somewhat protected here as a segment of the road was sunken and the troops could duck down as they hurried along it. But it was afterward named Bloody Angle for a reason other than British profanity.As the leading elements (the light companies of the 10th and 5th Foot) finally turned the corner at the top of this stretch and headed east again they looked back in relief that they seemed to have gotten past the worst part of the road. But unknown to them, 197 Minutemen from Woburn, under Maj. Loammi Baldwin, had been lying in wait behind the stone walls on both sides at this more open stretch. The provincials let the first company (the already disgraced light company of the 10th) trot by, and when the next company from the 5th came up, they let them have it from both sides. As before, they barbarously targeted the officers, hitting three of the four of that company. In the next minute of mad firing, they killed eight and wounded twenty in the two companies, or almost half. The British got none in return.

Parker's Revenge

Smith's men were only half-way to Lexington and the sniping seemed to be getting worse. Flanker companies fanned out to either side of the road where the ground permitted, but for much of it, they couldn't do this. This is where the dastardly colonials set up their ambushes. The British light companies, doing most of the fighting, jumping, and running, were also getting increasingly tired and running out of ammunition. Remember they had brought only 36 rounds with them that morning and Smith had declined any supply wagons so he could make good time.

He wasn't making good enough time now. He knew he had to keep up the pace because whenever his men got bogged down in clearing an ambush ahead, the rear guard would start to feel the heat from the growing numbers of militia pursuing them. These interruptions would also give time for the provincials to run ahead and set themselves up again. By the passage of Bloody Angle, it's been estimated that there were now over 2,000 militia around the dwindling British.

If a soldier was killed or too badly wounded to walk, his comrades just left him to the mercy of the "scalping" rebels. The story of the atrocity at North Bridge had not only spread but had been amplified to the point that the men were genuinely terrified. In reality, most of the British wounded were taken in by the local families to care for them. Those that were walking wounded hobbled along, helped by their mates, or put on horses by their officers.

The grenadier companies marching along the road, in their panic, started to trot, not march, and began to outstrip their flankers, exposing themselves to nasty surprises. A little over a mile from Bloody Angle, they had one.

About two miles out from Lexington Common, there was a wooded hill later called Parker's Revenge (appropriately enough). Its southern side hung steeply over the road and it was thickly covered in undergrowth to hide in. Capt. Parker, whose men had been so brutally abused on the Lexington Common eight hours before, had set an ambush with his rallied companies, reinforced to about a hundred men now, all itching for payback. This time he wasn't going to meet the British in a stand-up line, but in a concealed ambush. And he wasn't going to wait for them to fire first.

His men could see and hear the approaching firing. Eventually, they saw the red and white of the column approaching. These had to cross a bridge before they got opposite Parker's ambush position, with the already badly shot-up 5th's, 23rd's, and 43rd's light companies in the lead. (in that order). Col. Smith was riding with them. They had no scouts ahead of them since the duty flanker companies had fallen behind in some skirmishes some way back.

Parker let the ragged 5th's company pass right below him first, apparently relieved that this obvious ambush site was unoccupied. Then, at close range, Parker gave the order for his company to fire on the next two companies. The first volley hit several officers and men, including Col. Smith, a bullet in the thigh, falling off his horse. The Lexington men kept up a fast fire, knowing they wouldn't be able to hold this position long. In fact, Maj. Pitcairn rode up and took charge, directing some grenadier companies around to flank the Lexington men from the north and others to pour fire into the woods in front. Parker, realizing he was about to be overrun, managed to extricate his company after fifteen minutes, but by that time, one of his goals (aside from exacting vengeance on the men who had murdered his friends and relatives before) was to hold up the column in time for the colonials harassing the back of the column to run around and set up again in front. And he had.

While Pitcairn was rallying the men, his own horse, which had sustained a wound that morning at Lexington, got hit again, threw him to the ground and galloped off northward across the fields. He'd had enough. As an anecdote, this horse miraculously not only survived his wound and the war, but was caught by some Lexington people, cared for, and auctioned off to help the families of those men who had been killed that morning. Pitcairn's expensive pistols, still attached to the saddle, were later presented to General Israel Putnam who fittingly faced Pitcairn at Bunker Hill three months later. Pitcairn was killed heroically at that battle, but probably not by his own pistols.

Smith himself found another horse, but then turned it over to his protege, Ensign Lister, who had a worse wound. That young officer, in turn, gave the horse to an even more seriously wounded enlisted man, where it was later shot down. This was a bad day. Everybody, including Smith, limped on, sure that they were all going to die.

Just a mile from Lexington, in fact, they ran into yet another big ambush at a place called Fiske Hill and sustained even more casualties. After this, all of the light companies just gave up trying to screen the column at all and joined the grenadiers in what had become a rout. Nearly all of their ammunition had been shot off. They'd been up and marching for 17 hours. And they were getting tired of being shot by people they couldn't see or fight back.

When they finally started staggering into Lexington, the men were on the verge of completely breaking. Several had already fallen out and threw themselves on the mercy of the militia, who turned out to be unexpectedly gracious. The few officers who were not seriously wounded fixed bayonets on their own muskets and stood in front of the men on the Common to get them to stop and rally. But just then, as the officers faced down their men, everybody started to cheer at something behind them. They turned to see what they were so happy about and , there, about a thousand yards away, the hill on the east side of town was covered in lines of red and white. The familiar regimental flags of the 4th, 27th, and 43rd Foot as well as the Marines flapped in the sun. They were saved! The long awaited relief had finally shown up.

Percy to the Rescue

|

| Hugh Lord Percy, Earl of Northumberland At just 32, a rising star in the British Army until politics and discord with Gage's replacement, General Howe, forced him to quit in disgust. |

The column moved this time down the Boston Neck through Roxbury and Brookline. They marched slowly because Percy didn't want to tire them out in case there was a battle at the end of the march. He also rejected the army's artillery chief, Col. Samuel Cleaveland's insistence that he take a caisson of 140 extra artillery rounds with him as a precaution. He told Cleaveland this would slow them up, which was odd, considering he didn't seem to be in that much of a hurry. He told the artillery chief that the 24 rounds each piece had in its side boxes should be enough since he didn't think he'd even need that against the rabble. This was to incense Cleaveland later when Percy whined in his after action report that he didn't have enough artillery ammunition.

As Percy's column marched leisurely through Brookline, he sent his engineers forward to Cambridge to secure the bridge over the Charles there. The early worries that the provincials would destroy that bridge had convinced Gage to ferry Smith across the Charles the previous night. Those worries proved to be well-founded. The Cambridge militia had torn up all the planks of the bridge, but had obligingly stacked them neatly up next to it. By the time Percy's brigade got to the river, the bridge was well along in being fixed by his engineers and he was able to get his infantry across. He left the engineers to finish laying the bed on the bridge so the supply wagons could follow later.

These wagons did follow in a couple of hours, long after the First Brigade had marched through Menotomy, but as they tried to catch up they were intercepted by a company of old men at that town and later used as a mobile depot to resupply the militia with ammunition. So British attention to detail once again left a British army in the field with only the 36 rounds each man had in his pouch. Brilliant.

About 1430 Percy's column reached the outskirts of Lexington. He halted on a hill about a thousand yards from the Common and saw the first, sad elements of Smith's column staggering into the town from the opposite side. He also saw hundreds of militia firing at them from both sides. Setting up one of his guns on the hill, he had it fire a round in warning. The first cannonball went right through the front of the Meeting House and exploded dramatically out the back side. This, and sending a couple of more rounds at each side of the road at the militia, caused them to scamper away and let Smith's cheering men rush forward to meet him. He deployed three of his regiments along the ridge line, across the road, with the Marines held in reserve (see map below).

Cowed only for a few minutes, the thousands of militia who had been harassing Smith's troops, soon came back, all the while joined by more and more companies marching in from all over eastern Massachusetts. They realized that while loud the gun (Percy moved one of his six-pounders further back down the road to a hill covering the road near his headquarters at Munroe's Tavern) was not firing very fast and that its rounds were not presenting any physical threat to the skirmishing Minutemen and militia. So they moved in again to pester the last of Smith's exhausted troops and to start sniping at the formed regiments on the hill from the cover of the swamps and stone walls. Percy sent independent companies down in counter-attacks, which would bat away the provincials. But these would only come back again when the British companies rejoined their lines.

|

| Gen. William Heath

Love the shape of his head. It's no wonder

he was so loved and well-known among the militia rank and file. |

Percy waited while the last of Smith's demoralized and exhausted men filtered through his lines and made their way back to collapse around Munroe's Tavern. He wanted to give them a half hour or so to collect themselves before he began the march back. He was concerned to get everyone back to Boston by nightfall (1900). He also noticed that many militia were sneaking in to the farm houses around his position and setting up sniper positions. So he ordered all the houses nearby to be set on fire. This was the first time that day that private property had been destroyed. To Percy, there was now a state of rebellion (if not outright war) with the colonials. Before this, being a fairly liberal Whig, he had had some sympathy for the American cause and hated the benighted policy of the King and Lord North's government toward them. But listening to the tales of atrocity (like the "scalping" incident at Concord) and the skulking, murderous behavior of the militia (whom he regarded as delinquent civilians and not legitimate soldiers), he developed an instant contempt for them. All bets were off, as far as he was concerned.

So the handful of houses and barns on this side of Lexington were burned. Including that of the Mulliken family, where Dr. Prescott's girlfriend, Lydia Mulliken lived. (You remember Prescott, who the night before had joined Revere and Dawes in spreading the word of the British expedition on his way home from courting his love.) Percy gave Smith's men about thirty minutes to rest and then sequentially pulled his lines back to start the march home to Boston. He sent Smith's companies on ahead, thinking that all of the militia were already behind them, while he had his Marines take up the rear guard to hold back the hordes of rebels.

Unfortunately the way back was not clear as Percy had hoped. He noticed on his march up from Cambridge how quiet the countryside and deserted the houses seemed. He was assuming that it would be the same on the way back. What he didn't realize was what Smith's people already had, that the militia were running ahead and occupying woods, walls, barns, and houses in ambush. And even more companies were arriving from the coastal towns like Medford, Salem, Marblehead, Lynn, and towns to the south. By the end of the day, approximately 4,000 would have descended on the retreating Redcoats. And the troops who were going to get the worst of it were again Smith's long-suffering men at the head of the column.

He was also wondering where in the hell his supply wagons were.

The Last Leg

This realization that the battle was far from over came as Smith and his men started to march back through Menotomy. Militia and Minutemen were shooting from windows and from behind walls again. Percy sent flanker companies on either side of the town to sweep in and flush out the provincials. He also ordered the burning of buildings along the route behind them. And if any shots came from any windows, the troops were authorized to charge in and kill everyone inside. These enforcers also started to take the opportunity to loot the same houses. Soon, Redcoats were raiding the houses more for what they could plunder than just for security. Of course, this gave the Patriots even more propaganda ammunition.While, up to then, the casualty rate suffered by both sides was lopsided, with the British by far taking the worst of it, after Menotomy, the larger numbers of fresh troops of the First Brigade began to even the score. Militia would lie in wait behind a wall or in a barn only to be surprised from the rear by vengeful Redcoats, who were in no mood to take prisoners. Many were shot and then bayoneted multiple times to make sure they were dead. Others were flushed out of houses by setting fires and then shot while they tried to escape.

Of course, instead of deterring the patriots, this only made them madder.

After Menotomy Percy reasoned that going the way he had come, through Cambridge and back across the bridge over the Charles, would be foolhardy. He figured that if resistance were this stiff in Menotomy, it would be worse in Cambridge, and that the bridge itself would be more thoroughly destroyed than it had been that morning. And even if he were to seize the bridge and beat back the militia there, he would still have to fight his way back through Brookline and Roxbury to Boston Neck, at night. That would spell doom for the entire force, which was half of the British troops in all of New England.

So he decided on an end run. At the fork between Cambridge and Charlestown, he saw a large formation of militia blocking the road south to Cambridge. He unlimbered his two guns and sent off a couple of rounds in their direction, scattering them. Then he took the left-hand road, toward Charlestown. Like Boston, that town was on an isthmus linked to the mainland by a narrow neck. The road there was through relatively flat, open country with no other dense villages to have to fight through. If he could make it there by night, he could set up a defensive position on Bunker's Hill facing the neck. He could then ferry his men back over to Boston safely that evening.

As it turned out, this head fake worked perfectly. Most of the militia, being under no unified command, had assumed the British would go back the way they had come and had hurried down to Cambridge. By the time any of them realized Percy was heading east instead, he was far ahead of them. By 1900 the rear guard Marines had crossed the neck (see strategic map at the top of this article) and dug in on Bunker Hill, Percy's two six-pounders sweeping the neck from that position. This position also put him under the protection of the Royal Navy's guns in the harbor.

Hearing about the devastation the British were wreaking further west, a delegation of selectmen came up the hill from Charlestown to promise that they would not interfere with Percy's troops if they would not burn the town. Percy, mad as a stomped-on cat by this time, assured the town elders he would do just that if so much as one person poked a gun out of a window. He also made them promise to take care of his wounded and to assist in ferrying them back to Boston.

Smith's companies, who had been on their feet for almost twenty hours and under more or less continuous fire for nine, were ferried back to Boston first. Gage sent two fresh regiments under Gen. Pigot (10th and 64th Foot, center companies only) back over to Charlestown to reinforce Percy, along with ammunition and provisions. Percy's brigade stayed there for the next week, after which they were evacuated back to Boston.

The militia, who had also been up and racing around eastern Massachusetts and fighting all day, also settled down for the night. But troops from all over New England, including from Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Connecticut, as well as the northeastern section of Massachusetts (later Maine) were marching to surround Boston. Within just two days the Patriot Army had grown to 20,000 besieging the city, defended by just 4,000 Regulars. The Provincial Congress voted to raise the army to 30,000, and appointed a number of general officers to organize and lead it, men like Heath, Israel Putnam, Artemis Ward, and John Thomas. But there was still no formal overall commander-in-chief of all Continental forces. That wouldn't come until the end of the year when the Continental Congress appointed George Washington to take command of all the forces besieging Boston.

Aftermath

What had started as one more routine expedition to seize military contraband, something that Gage's troops had done several times before, ended up in a severe military defeat for the Crown. It also sparked a full scale war, something that Parliament could ill afford, both politically and fiscally, since it was still up to its neck in debt from the Seven Years War a little over a decade before.

In addition to the colossal political blunder to the Crown's interests, the ill-planned and worse-executed expedition also cost the small British garrison in Boston 273 casualties (including 73 confirmed dead), nearly 7% of its total strength of 4,000. In contrast, even with the increased ferocity on the part of the British at Menotomy, the Americans suffered only about 100 casualties (including 49 killed outright). From a statistical point of view, this disparity, 14% vs 2.5%, gave the "embattled farmers" an overwhelming tactical victory in this first battle.

Of course, this was just the beginning, and it would not all be so lopsided in favor of the Americans. The next several months saw Boston besieged, reinforcements bringing the British (under three new generals, Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne) up to 11,000, a pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill, the creation of a Continental Army under George Washington, and ultimately the evacuation of Boston by the British. Of course, too, the next few years saw defeat after defeat for the Americans. It was a dark time and the country was nearly still-born. It could so easily have gone the other way. The way of Canada, perhaps.

Lexington-Concord: Post Mortem

1. Asymmetrical Warfare: Regular vs Irregular

As a set piece, and isolated from its political significance, the running battle that took place on 19 April 1775 was interesting in that it showed the superiority of the new light infantry tactics against the formalized linear warfare of 18th century Enlightenment. Of course, the American Revolution was not the first time these tactics had been used. The Austrians' Grenzer irregular troops used them for decades up to now in Europe. And in America, these had been used by the colonists (both French and British) alongside their Indian allies for over a century. Many of the Minutemen, in fact, had fought with Roger's Rangers during the French and Indian War.

The British line regiments had acknowledged the usefulness (and threat) of this new style of warfare by designating so-called light, flanker companies in each regiment, whose mission was to guard the flanks of the close-order battalion from harassment by enemy snipers. But they were, by the beginning of the American Revolution, rarely adequate in their training to do this; certainly not nearly to the degree the Americans were. This was the style of warfare that suited the Colonials. And Lexington-Concord was the first experiment pitting these two tactical doctrines.

Lord Percy, though contemptuous of the rebels, nonetheless acknowledged their combat effectiveness in his reports. He warned his superiors and colleagues against the mistake of assuming that the Americans were an inconsequential military threat. He complimented the provincial's tactical skill and courage. In fact, this makes me think of similar warnings that many American officers gave the Pentagon about the Viet Cong in the 1960s, who were also, at first, also dismissed as inconsequential.

In modern military theory this is called "asymmetrical warfare". But it is not a new thing. It happens whenever one side, coming from a position of conventional weakness, is forced to apply unconventional methods to first resist and then wear down its foe.

2. Fighting Retreats

The other feature of Lexington-Concord that stands out is how similar it is to so many other fighting retreats in history. The narrative seems so familiar, like Xenophon's 10,000 retreating from Persia in his Anabasis of 370 BCE, or the Crecy campaign in 1346, or Napoleon's retreat from Moscow in 1812, or even the destruction of Varian's Roman legions by the Germans in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE. In this latter, the Romans found themselves suddenly set upon by people they had assumed were their friends and allies. And, of course, of interest in this month, Dunkirk in 1940.

Fighting retreats can often reveal the most heroic and best in human nature, demonstrating resolve and strength, as Xenophon's men and the BEF at Dunkirk revealed. But they can, as at Lexington-Concord, also show the worst in human nature.

3. Appalling Leadership

One of the most distinguishing aspects of Lexington-Concord to me is how terrible leadership and lack of military professionalism can result in disaster.

First there was the sloppy security exercised by Gage and his staff in the few days before Smith set off. It took almost no time for everyone in Boston, and then everyone in Massachusetts, to know what was coming and where the British were going. Everybody, ironically, except the men who had to go do it. If such a thing had happened today in a modern army, the whole operation would have been cancelled. As it was, though Gage himself was aware of the security breach (even in his own household) he just shrugged his shoulders and sent Smith off anyway.

Then, as Smith's column got underway (four hours late) and made it to Lexington, all of the officers just allowed the men under their command to get out of hand and start a riot among themselves, going after the otherwise passive militia. Some of them, like Maj. Mitchell, were directly responsible for fomenting the riot. This lack of control of their own troops was to show itself again at the North Bridge, and all during the retreat back to Boston. While here and there a British officer would show conscientiousness and control, for the most part they might just as well have not been there.

Add to this the ridiculously sloppy staff work on display. That orders were repeatedly delivered to the wrong address, without receipt confirmation, causing hours of delay, cost lives. Officers were also sent on missions with little guidance as to rules of engagement or mission. Many officers were also assigned to commands that were complete strangers to them.

To anyone today who has been a part of a modern military, reading about the slapdash manner in which things were done, in which security was so lax, and in which leadership was entirely lacking, it is not hard to see how this disaster happened.

4. Relative Combat Efficiency

Many stories that I grew up with as an American cast the Colonial militia that responded to British oppression on 19 April 1775 as gifted amateurs, standing up to the "most powerful military in the world." attaining victory only through the righteousness of their convictions. However, in looking more closely at this battle, it seems to me that it was the poor British soldier who was the amateur, facing a force of thousands of well-trained, highly motivated combat veterans who knew how to fight in broken country. Few of the rank and file of the British regiments had seen any combat, but neither had most of their officers, most of them had been shipped over from garrison duty in Ireland and had not participated in the Seven Years War. The opposite was the case with the Minutemen and their officers. While the Colonials may not have had much in the way of higher command, on the company and individual level, they completely dominated their redcoated adversaries.