American Civil War

Wednesday, 17 September 1862

Army of the Potomac under George B. McClellan: approx 74,000, 294 Guns

Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee: approx 35,000, 230 Guns

Weather: Rainstorm the night before, ending in the early morning hours. Ground fog at dawn for an hour or so. Otherwise clear, though the air was apparently windless and heavy, becoming "smoggy" with gunsmoke pretty quickly.

Sunrise: 05:53 Sunset: 18:16

( NOAA Improved Sunrise/Sunset Calculator from date and coordinates)

Moon in waning crescent, not rising until 00:38 on the 18th. So it was a black night.

Geo Coordinates: 39° 28’ 12” N, 77° 33’ 24” W

Caveats: Okay. Let me be upfront right off. This isn't an obscure battle to aficionadi of the American Civil War. Get over it. I named this domain "Obscure Battles" for this blog years ago, when my first articles were a series of obscure battles (to most normal people). And I have since done battles much more well known--at least to people who paid attention in their high school history classes and don't get all their information from Tik Tok. So it is with this.

As usual, my own take on this battle is what is obscure. And, I'm sure, wrong.

Perhaps as much as any battle in American history (or world history for that matter), Antietam is rich with detail and anecdotes of the fighting. I have to admit, in writing up this vast battle, it is tedious to cover all of it. For those of you wanting juicy, minute-by-minute accounts I heartily recommend Stephen Sears' book, Landscape Turned Red, or John Priest's collection of personal memoirs, Antietam: The Soldiers' Battle. These and other books listed in my bibliography below. Otherwise I'm going to cover the broad action.

A Personal Note: Two decades ago I visited this battlefield and spent three days

there walking over almost every inch of the ground, listening to Park

Rangers/Historians (like Paul Chiles) describe the battle. So it has a

personal appeal to me, something I had meant to write about and do maps

of for some time. So while this is not an "obscure battle", it is certainly something I have been working on for several years.

This map shows unit positions at the beginning of the battle, from just before sunrise to about 06:30. Details of the ground, the nature of the crops in the fields, the fences and roads, were derived from the incredibly detailed series of maps done by Carman and Cope from 1899 to 1908, on the Library of Congress's Website. The footprint of the unit markers are to scale, based on reported or estimated strength levels. ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

A mess of a battle that ironically saved the Union and freed four million Americans from slavery

Because my country and its media seem to be writhing in the dark fantasy of another impending civil war (I mean, wouldn't that be fun?), I've been thinking of and re-reading histories of our last one. As with all contemplation of history, the parallels are chilling. And frustrating how we never seem to learn. But fortunately there are also fundamental differences. Nevertheless, I felt compelled to deal with this battle, which though a tactical mess, turned out to be a turning point, not just in the American Civil War, but in the history of human rights in my country and the world.

Toward the late summer of 1862— well into the second year of the war—things were looking pretty dire for the survival of the American republic. Though there had been some Union victories in the West (Shiloh, Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, Pea Ridge, and New Orleans), and though the Confederacy was increasingly blockaded from its trade with Europe by the U.S. Navy, things were not looking good for the United States. Anti-American parties in Europe's two superpowers, the U.K. and Napoleon III's France, were clamoring for their governments to intervene and put an end to the American experiment in self-government, which had too long been regarded as a bunch of arrogant, shrill trouble-makers. The textile industries in Europe were also in terrible recession because of the cut-off of Southern cotton due to the Union blockade. While the U.K. would eventually exploit its recently acquired empire in India as an alternative source of cotton and though there was enough warehoused supply in England to last until the end of 1862, that country faced record unemployment in its huge textile industry. Because of this, the Civil War was having a political knock-on effect on Britain's Liberal Palmerston Government. Even though Britain and France had both outlawed the slave trade in their own empires, they hypocritically reaped economic rewards from its continuation in the United States. They were getting intense domestic and political pressure at home to end the American Civil War, to recognize the Confederacy (even with and especially for its slavery), and to get on with life. Sheeze!

President Lincoln

had long realized that the true animus behind Southern secession and the

war had been slavery. He ran for office on eradicating it. And when he

was elected, the Southern state legislatures, anticipating his

anti-slavery agenda, just took it upon themselves to start leaving the

Union one after another, as some (especially South Carolina) had been

repeatedly threatening to do practically since the Constitution was

ratified 72 years before. It's a threat we've heard time and time again

ever since, whenever certain states think their "rights" as states have

been violated by a "tyrannical" Federal government. I don't think an

election year goes by without Texas threatening secession.

By

the second year of the war, Lincoln realized that in order to retain

the continued backing of his own newly-formed Republican Party, he had

to move toward Emancipation, but without losing the remaining slave

states in the Union to secession (Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and the

soon-to-be newest state of West Virginia). This was also a midterm

election year, and, as in most midterms, the incumbent party was worried

about losing seats in Congress. So "Abolitionist" Republicans were

clamoring that something be done to move forward the single issue that

had swept them into power in 1860 in the first place. This issue was

something that was the elephant in the room. (Get it? "elephant"?

Republican Party?...oh, never mind.)

But there was a slight problem.

Up

until the summer of 1862, except in the West as I mentioned above, the Union had been

suffering defeat after defeat on the battlefield. The two major European powers, Great Britain and France, were debating whether to intervene to

impose an end to the war and recognize the Confederacy, and resume their

importation of cotton, which, as I said, was vital to those countries'

textile industries. For Britain, the strongest of the European powers

(economically at least), the hypocrisy of backing a slave power like the

Confederacy held a political booby trap. Britain had officially

outlawed slavery since 1834 throughout their empire (well, officially

anyway). Certainly there was mass unemployment and recession, but to

come to the open defense of slave drivers would have spelled political

suicide in the Palmerston Liberal Government. The Tories were loudly clamoring for intervention, hoping for the final end to the American "experiment" and the re-acquisition of Britain's North American colonies. Parliament and the Palmerston government were being

lobbied heavily by Confederate emissaries to do so, citing their

faction's cavalcade of military victories in Virginia and Kentucky.

Napoleon III of France was personally less anti-slavery, or at least indifferent to it, and somewhat prone to support the Confederacy if it would back his long attempt to add Mexico to his empire. But it was still a political gamble for him to openly support another country's secessionist region if doing so would harm his own country's economy. Also, like the U.K., France had officially abolished slavery throughout its empire at the inauguration of the 2nd Republic in 1848. But the French economy was still limping from its stalemated war against Austria in Italy two years before. And Napoleon III's adventure in Mexico was stalling (e.g. the disastrous French defeat at the Battle of Puebla on el Cinco de Mayo five months before). So the Confederate envoys were hopeful they could persuade the French dictator to back their case for recognition in exchange for supporting the claim of his hoped-for client, Emperor Maximilian I (and Last) of Mexico (actually, and ironically, an Austrian.)

But by September the

American government was sensing things could flip either way for it in

Europe. An intervention by either Britain or France could spell disaster

for the Union. Much as an intervention by so-called "neutral" powers to enforce a ceasefire in Ukraine could spell disaster for the existence of that country today.

Though Lincoln had drafted and polished his

Emancipation Proclamation since July of 1862, he felt and was advised by

his cabinet and party that, if issued prematurely, it would merely seem

like a last, pathetically desperate gesture, and might actually

precipitate foreign intervention. He was also worried about losing the

four remaining slave states (so you don't have to scroll up: Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, West Virginia). He'd

also risk losing the backing of the wavering pro-Union Democrats in the

North, who weren't all that keen on emancipation, which their base

considered an entirely different issue from secession. There was a

midterm election looming in November and Lincoln was worried about

losing his Republican majority in Congress. If all of these threats were

to materialize, the country would go down blub-blub, without having

practically emancipated one enslaved person or saving the Union.

As I reread all of

this history of my country's Civil War, I was struck by the parallels in

our own times with the economic and political stress all of the NATO

countries and other democracies in the world are feeling from Russia's

current invasion of Ukraine. All of the free democracies have declared

moral opposition to it, and doing what they can to support the

Ukrainians, but they are also suffering economically from the sanctions

on Russian energy exports and most recently by the grain blockade

re-initiated by Putin's Russia on Ukraine (reneging on an earlier agreement not to interfere with those). In 1862 the British and French, as well as smaller European countries, were feeling the same moral vs economic dilemma vis-a-vis the American Civil War, but over cotton instead of fossil fuels and grain. The only factor that isn't the same is that no one had nuclear weapons back in 1862.

So,

by September, Lincoln needed one game-changing victory in the East,

closer to Washington and the press, before he felt he had the political

capital to issue his Emancipation Proclamation and give the country that

higher moral purpose for the war. It was initially about secession, of

course; but the reason the Confederate states seceded in the first place was their

opposition to emancipation. They were inextricably linked.

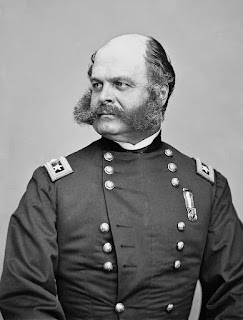

|

| George B. McClellan Posing as "The Young Napoleon" He did love to pose. |

Yet Lincoln's tools were dull.

Frustrated

with the string of incompetent generals he had appointed to lead the

Eastern Theater armies, who all had presided over defeat after defeat,

and after the last humiliation of Second Bull Run

in mid-August, Lincoln was forced to offer the command again to George

McClellan. The President was reluctant to do this because McClellan had

spectacularly failed in his Peninsula Campaign in Virginia earlier in

the year. "The Young Napoleon", as his fawning entourage and the Democratic press

nicknamed him, actually won battle after battle in that venture (the Seven Days Battles),

inflicting horrific casualties on the outnumbered Confederates. And yet

after each tactical victory, seizing defeat from the jaws of victory, The Young Napoleon would retreat. He did this over and over until he

backed himself against the James River. Lincoln, exasperated by

McClellan's ineptitude, cowardice, and weak excuses, finally ordered him

to pack up and come back to Washington, relieving the Young Napoleon of

command. "Little Mac" (as he was supposedly also fondly known by the Union

soldiers, though I suspect that was so much press puffery too) blamed

his failure in the Peninsula on Lincoln (whom he dubbed "a Well-Meaning Baboon" and, "the Original Gorilla"...and probably other simian

epithets) for not sending him enough reinforcements, and ammunition, and other supplies. He had been

complaining throughout the campaign that instead of vastly outnumbering the

Rebels (as was actually the case), it was he who was outnumbered; his estimate of Lee's army growing by 100,000 each week.

McClellan

was one of those blustery generals who was more concerned with the

press and his self-image that with actual fighting. He frequently wrote

his wife, Ellen, describing himself as the country's savior, appointed

by God. He actually wrote this, over and over. He must have been a eye-rolling joke for those non-sycophantic officers on his staff and under his command.

And certainly we've seen enough of his self-anointed, "heroic-victim"

type in our own time (not naming any names). I have long wondered what Ellen, his wife, really

thought of him. Did she "Yes, Dear," him throughout the war?

The

Confederacy, on the other hand, was blessed with McClellan's almost exact opposite. Robert

E. Lee had been appointed command of the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV)

by President Jefferson Davis since the wounding of its previous

commander, Joe Johnston, during the Battle of Seven Pines during the Peninsula Campaign.

It was Lee who was responsible for the bitch-slapping of the Army of

the Potomac month after month throughout the summer of 1862. Though the

Union troops in Virginia had fought ferociously, they had been led by

one incompetent commanding general after another (including McClellan).

Lee seemed unstoppable. Even when he lost a battle (as he did

throughout the Seven Days Battles and would again at Antietam—ooops,

spoiler), he never quit. And his men grew to feel they were invincible,

even when hungry, barefoot, and skinny from starvation. The prevailing

myth among them was that one Johnny Reb could lick ten Billy Yanks.

Mindful

of the global implications of the Confederacy's survival, Lee and

Jeff Davis concurred that while the ANV was beating the Yankees in

battle after battle on Virginia soil, it was strategically vital to take

the war up North to prove to the world's superpowers that the

Confederacy was going to win, and that it would be best for those powers

to intervene to back its independence. Oh, and yeah, to resume the flow of cotton to European mills—an economic crisis I'll elaborate on below.

And even though the South was for

the time winning battle after battle in Virginia, the fact that so much of the war

was fought in that state meant that Virginia farmers, commerce, and

people were suffering. It was another reason to take the war into the

North. Make the people of Maryland and Pennsylvania suffer and see how

long they'd support the war. Also, many in the South were

convinced that the people of Maryland would rise up and join them (being

in a slave state themselves). This was based partly on the Confederate

misperceptions of the significance of the Baltimore Riot in

1861 and the somewhat pro-Confederacy sentiments in eastern Maryland,

particularly on the Chesapeake. But western Marylanders were, for the

most part, not pro-secession at all. They wanted to stay out of it. It

reminds me of the gross miscalculation that Vladimir Putin made of his

reception in "liberating" Ukraine earlier in 2022. Like the Ukrainians,

the white people of western Maryland had no interest in being "liberated" by the

Confederates. In fact, as Lee was to find to his chagrin, his invasion

would set off a virulent pro-Union backlash in Maryland.

Meanwhile,

after its humiliating defeat at Second Bull Run, the Army of the

Potomac had been reforming around Washington. As I earlier pointed out,

Lincoln felt he had no choice but to fire its latest hapless commander,

John Pope, and, running out of available talent, reinstate McClellan. As

the Young Napoleon had initially organized the Army of the Potomac, he

seemed the likely man to reorganize it. Lincoln, though, was not

optimistic about McClellan; he just felt he had no other option at the

time.

|

| Not all papers admired "The Young Napoleon". |

This

historic claim to his popularity has always mystified me. When

McClellan was the Army of the Potomac's commander during the Peninsula,

he had not exactly shown brilliance, nor followed up the repeated

battlefield victories of his troops with strategic offense; he just kept

retreating and retreating until his back was to the James River. But then his

reputed military genius may have been propped up by biased reporting

of the press lackeys who were following McClellan, Democrat-biased papers like The New York Herald,

as well as the subsequently published letters the Commanding General

himself had written to his wife, whining about how nobody appreciated

him and that he had only nit-wits to work with... blah, blah, blah. In fact, he said again and again how

nothing was his fault; it was always those "traitors in Washington" who

wouldn't send him enough troops. Or sandwiches.

Since some isolated experiences during the Mexican-American War fifteen years before, he also had no actual combat experience. The only other battle he had remotely been close to was Rich Mountain in

1861, where, like the Peninsula and, we'll see, later Antietam, he had led from the

rear. This small battle he prematurely assumed he lost because he heard

Rebel cheering in the distance. But it was his subordinate, William Rosecrans, who counterattacked and beat the Confederates, a feat which Li'l Mac was quick to take credit for.

I

have long wondered if McClellan's reputation for popularity with the

army was only in his own imagination and that of his entourage of press

sycophants. The Civil War was seventy-five years before George Gallup

invented the first public opinion poll. So back then the best political

assessment of the mood of the electorate was taken by the mood of the press,

of which each paper was extremely partisan (Not like today.). Lincoln knew this, and was

skeptical of the Democratic press's claims of McClellan's reported

popularity. But Lincoln himself was not so prescient as to flaunt

McClellan's appeal to the troops reported in those papers, or among the

Northern Democrats still in Congress. Lincoln was a consummate

politician, so for the most part went by his gut instead of polls or newspaper opinions.

But the president was galled to have to turn back to McClellan, who had shown Lincoln and his whole cabinet unconcealed disdain for months, and had displayed himself as a self-preening clown. When he had been ordered to go to the reinforcement of General Pope fighting the Second Battle of Bull Run, he blatantly held his Army of the Potomac back until Pope was defeated. Talk about traitors!

But things changed with Lee's crossing the Potomac, putting the capital itself in peril. Lincoln felt he didn't yet have anyone else he could turn to. The president had been warned by his staff that McClellan (a rabid, anti-abolitionist Democrat) had political ambitions himself and there had been rumors of his plotting to turn on Washington and install himself as a military dictator. But, in extremis, Lincoln felt he had to work with the tools he had in his box. And McClellan was certainly a tool. Lincoln later wrote to another AOTP commander, General Hooker, when he subsequently turned to him to command, even after rumors of Hooker's off-record remarks about himself installing a military dictatorship, "What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship." I'm sure he was thinking of that in having to turn to McClellan in September 1862.

"We'll be welcomed as liberators!"

Three

days after Second Bull Run (2 Sept), Lee decided to act. After

replenishing the ANV from the captured Union depot stocks at Manassas

Junction, he began to move his army of 50,000 up to White's Ford on the

Potomac, just 23 miles up river from D.C. Freed of the threat to

Richmond by the withdrawal of nearly all the Federal troops back to

Washington, and of the perceived diplomatic need to goad the European

powers into recognizing the Confederacy's viability, Lee and Davis both

recognized that now was the time to take the war north to prove that the

South was winning their independence.

Unfortunately, as the ANV started

moving, it was subsequently reduced by desertion of an

estimated 15,000

men who, tired of fighting barefoot and starving, reasoned that they

had done their part by

driving back the Yankees from their home states.The Southern enthusiasm for their war of independence was not universal, and, in many

cases extended no farther than the gates of their own farms. The saying among the Confederate rank-and-file was, "Rich man's war, poor man's fight." As few as 10% of soldiers owned slaves themselves, and as few as 25% came from families who did. It was the principle of the thing to them. And they were also inflamed by the Southern press, politicians, and their own preachers that the freeing of slaves would unleash rapine and murder upon their families (a familiar argument by anti-immigration politicians throughout American history, up until and including today).

Also many soldiers in Lee's army felt that they had been lied to when they had originally signed up for a twelve month enlistment, only to have their government rescind that agreement that April and unilaterally extended it to three years, or "the duration of the war" (a vague loop hole). The Confederate Congress thereby enacted the first universal conscription act in American history, drafting all men from 18-35. So much for fighting for freedom! These admittedly war-time laws flew in the face what these patriots had volunteered for; liberty. So thousands of those one-year Confederate consignees were deserting in droves, believing they had been betrayed, and, at the very least, had done their duty by defending their home state (not the Confederacy at large).

After all these desertions, by the time Lee had crossed into Maryland his

army was down to about 35,000. But, it must be said, those remaining

were the most dedicated—and lethal.

The first units started crossing on 4 September. Fortunately the water level on the Potomac at this time of year was low, so the men took off their pants (and what shoes they had) and, balancing these and packs and muskets on their heads, were able to wade across the 360 yard (320 m) wide river relatively easily at White's and Cheek's Fords. By the 7th nearly all of the remaining men of the ANV had crossed into Maryland.

Pants off, everybody! White's Ford looking from the Virginia side of the Potomac. (You'll have to pardon my crude mosaicing of the panoramic image. I made it from a sequence of shots I took in 2001 with my old, manual Nikon F.) ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Like

the current invasion of Ukraine by Russia we are witnessing in our own

time (or should I say, "Special Military Operation"?), Lee and Davis

had grossly misjudged the reception they expected in Maryland. As I mentioned above, they had

anticipated that Maryland, a slave state itself, would, when

"liberated", rise up and join The Cause. This miscalculation stemmed

from poor local intelligence and an over-reliance on the pro-Democrat

Baltimore press, suggesting that all of Maryland was ready to join the Rebellion. Eastern Marylanders did tend to sympathize with the South.

But not Western Marylanders, through whose towns and farms the ANV now

marched. Many people defiantly displayed Stars-n-Stripes flags from

their windows, including the immortalized 95 year-old Barbara Fritchie in Frederick, who was misquoted in Whittier's jingoistic poem,

"'Shoot if you must, this old grey head/But spare your country's flag,'

she said". There has been considerable controversy if this incident

was Barbara herself, or other women in other towns the Secesh army

marched through. There were several anecdotes of women waving American

flags from their houses, and some reports of women wrapping themselves

in that flag and daring the Rebs to shoot them. Mostly people watched

the marching Johnnies out of sullen curiosity, but decidedly, not cheering. So in spite of the optimism of thousands of pro-secession Marylanders

joining their ranks, fewer than 200 did, hardly enough to replace the 15,000 deserters "who had done enough."

The ANV now fanned out into several enterprises. Though it is commonly thought to be a cardinal sin in war, Lee, though usually on the numerically inferior side, frequently split his force to confuse the enemy. It was one of his signature moves. To him, that enemy was a single man, McClellan, and from his experience with the Young Napoleon in the Peninsula, he felt he knew his boy. Lee could split up his army and spread it all over western Maryland and knew that McClellan would take no chances, move slow, (the Northern pro-Republican press had nicknamed him "Tardy George"), and not be a problem.

Black Americans being driven to Virginia from Maryland as "contraband" by Lee's cavalry.

I'm sure these people welcomed their Liberators. Harper's Illustration, Nov 1862

,%20p.713..jpg) |

Also, during this and Lee's subsequent invasion of Pennsylvania the next year, Confederate cavalry took it upon themselves, in their confiscation of private property as a necessity of war, to include the confiscation (or, let's call it what it was, kidnapping) of Black Americans as "contraband", driving them back into Virginia to be sold as slaves. Many were legally free citizens of Maryland. It didn't matter. Though there doesn't seem to be direct evidence that Lee himself officially ordered this slave raid on Americans, he certainly turned a blind eye on it.

Lee had written a secret order, the infamous Order 191, to four of his generals (Longstreet, Jackson, D.H.Hill, and McLaws) to take their respective commands in four directions. Longstreet was to take 10,000 men and move northwest to Hagerstown, near the Pennsylvania border. D.H.Hill was to follow with his 5,000 and block the northern passes over the long South Mountain into western Maryland. Jackson was to take his corps , about 13,000, up to seize Martinsburg on the upper Potomac and then back down the Virginia side to seize the main Federal depot at Harper's Ferry at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. John Walker was to take his 3,400 up onto Loudon Heights on the Virginia side of Harper's Ferry to shell if from that dominating position. And finally Lafayette McClaws was to take 7,000 men (including Dick Anderson's division) and occupy the southern part of Elk Mountain, overlooking Harper's Ferry from the Potomac's Maryland shore. It was a bold and complex operation. (See map below.)

Movement of forces from the 3rd to the 13th of September. Remember,

light source on the mountains is coming from the bottom right...you

know...where the sun rises. People have objected t the way I portray

shadows in these maps as confusing, thinking that, conventionally, one

should portray shadows coming from a light source to the upper

left...oh, never mind. ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Windfall in the Grass: Special Order 191

Windfall in the Grass: Special Order 191

|

| Copy of Special Order 191 discovered lying in a meadow and hand delivered to General McClellan, potentially changing the war. Or not. |

When McClellan received this unlikely intelligence windfall the morning of Saturday, the 13th,

one of his staff officers, who had worked with Jackson's chief-of-staff

before the war, verified the signature and handwriting, and therefore

the authenticity. McClellan immediately realized this gift of fate and,

jumping up, exclaimed, "Now I know what to do! Here is a paper with

which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home."

Anyway, that's what he wrote his wife Ellen that he said. Oh, had she

but been there to applaud his dramatic soliloquy! Her hero! (Or, "Yes,

dear, that's nice.")

Guess what: He did nothing. Good ol' Li'l Mac never disappointed. For six hours after receiving this decisive intelligence—all day long, in fact—no orders were issued. The Army of the Potomac just settled in around Frederick. Then after sunset, McClellan finally got around to writing orders for his commanders for the following morning—as if Lee's army were just settling in too.

But

the incredible intelligence that Lee had split up his army ironically

reinforced another of McClellan's fears. It validated his belief in the

overwhelming force under Lee. No responsible commander would dissipate

his force unless that force was vastly superior to the enemy. So George

reasoned, and it was seconded by his incompetent intelligence chief,

Allan Pinkerton, that Lee must have 200,000—no, make that

half-a-million men! Lee, himself reading all of the same Northern

newspapers that McClellan read, knew about McClellan's delusions, and

probably chuckled to himself, knowing that it would inhibit Tardy

George's reaction. Some historians have speculated that the leak of

Lee's plans was deliberate, with the goal of reinforcing McClellan's

belief in the size of the ANV. But it would seem to be an inefficient

way to plant a psych in a package of cigars in a random field, hoping

some random soldiers would just happen upon it.

So, before the decisive battle is even joined, both sides commit colossal blunders: 1) Lee spreads his army out and, through criminally lax security, blows his plan to his enemy. And 2) McClellan gets this God-given look into his adversary's plans and vulnerabilities, and fails to act.

But wait... it gets better...

South Mountain and Harper's FerryIt wasn't until Sunday the 14th that the Army of the Potomac started to move towards its objectives, the two gaps through South Mountain (Turner's and Crampton's), with the target being Longstreet's Corps, cutting it off from Jackson and McLaws off to the south, besieging Harper's Ferry (See map above). Of course, during the night, Lee's own spy on McClellan's staff had plenty of time to get word to him that the Yankees had his plans and were getting ready to act. Lee ordered Longstreet to pull back to Boonesboro from his foray up to Hagerstown, and for D.H.Hill to move his 5,000 men back to Turner's Gap (the northernmost pass) to fortify it and block the Yankees. He also alerted McLaws and J.E.B. Stuart to send over some troops from their expedition to Harper's Ferry back east to block Crampton's Gap, about 9 miles south of Turner's Gap. Their mission was to delay the advance of McClellan long enough for Lee to pull in his army and find a defensive position...let's see...ohhhh...here...at this little town called Sharpsburg (imagine a cinematic zoom-in shot of a map with Lee's finger pointing to the spot.)

Action at Turner's Gap on Sunday, the 14th. Library of Congress

The actions around the three gaps over South Mountain got lugubriously going as the first Union troops under Burnside and Franklin started making their way up three paths through the woods, eventually encountering D.H.Hill's Confederates and some of McLaws' troops waiting behind some stone walls. This battle unfolded slowly as more and more of the Union First, Sixth, and Ninth Corps brigades came up over the long day. At first Hill had only a handful of men and guns to hold back the Yankees, but gradually Longstreet fed him more and more. Eventually, by the end of the day there were something like 28,000 Federals and 18,000 Confederates engaged, with a total of about 5,000 casualties between them. The Yankees didn't break through on that day, owing to the slowness of McClellan again, and Lee's men withdrew after the sun went down, having felt they had done their job of holding off the Blue Wave long enough for Jackson to take Harper's Ferry and Lee to prepare his defense at Sharpsburg. So let's give South Mountain to the Confederates— at least strategically.

Jesse Reno (after whom Reno, Nevada was named—but you probably already knew that), commander of Ninth Corps, was the only decisive general under McClellan that day, and had led his men first up the hill at Turner's Gap that morning. He was, unfortunately, shot dead early in the fight. The other commanders—Burnside, Franklin, Hooker, and finally, McClellan himself— just didn't feel the urgency. Some, like "Baldy" Smith (2nd Div, Sixth Corps) and Darius Couch (1st Div, Fourth Corps), were AWOL the whole damn day. Smith said he got a late start. And nobody seemed to know where the hell Couch was; he showed up late that night, explaining he got lost. Yeah, right. McClellan, as usual, was no help at all. Unlike Lee, who kept close touch with all of his commanders, McClellan just didn't seem to care. He was busy posing for the press and writing love letters to his wife about how he was about to go into battle. He was a commander that loved the idea of being in charge but just didn't like to do the actual charging.

Meanwhile, down south at Harper's Ferry, the Union garrison commander, Col. Dixon Miles, was busy doing nothing as well. By the 13th he had let himself be completely surrounded by Jackson, Walker, and McLaws. He had originally about 11,500 men under his command, and this was added to by another 2,500 when Gen. Julius White retreating down from Martinsburg in front of Jackson's wide sweeping movement (see campaign map above). Gen. White, though senior to Miles, deferred to the colonel out of respect for that officer's long veteranship (38 years in the Army), while Miles was merely a businessman who had obtained his commission from political favors at the start of the war. Before the 13th Miles had more than enough men to eject McLaws' and Walker's troops from the Maryland Heights to the north and the Loudon Heights to the east across the Shenandoah River. But aside from a contingent he dispatched up to Maryland Heights, he chose to sit tight, explaining to his complaining officers, "I am ordered to hold this place and God damn my soul to Hell if I don't.." When Jackson showed up at the Bolivar Heights overlooking the town from the west that morning, the Confederates had a superiority of two-to-one and three dominating positions, with more than 50 guns. Miles stayed put. Though his men had been fighting off the Rebs, and even managed to push them back from Bolivar Heights on the 13th, he ordered them back down the hill into the town. A squad of Union cavalry under Capt. Charles Russell crept out of town late that night and made its way up to find McClellan in Frederick. McClellan did write orders for Franklin to break through Crampton's Gap and relieve Harper's Ferry, and sent three couriers to Miles with orders to hold on at all costs; that help was on the way. But those messengers never managed to reach Miles.

By the morning of the 15th, after a day of relentless bombardment, Miles told his officers he had done all he could and had decided to surrender. His officers and men were furious. They told him they could break out, across the pontoon bridge to Maryland and fight their way up to join McClellan. But Miles sighed and said no, it was all over. Unfortunately (or fortunately), a cannonball hit him in the leg at that moment and he died the next day, ingloriously and in agony (and, based on his oath from the previous day," damned in Hell"). His successor, Gen. White, chose to obey Miles' last order and surrender the town, all its magazine and stores, and 12,600 men without further resistance.

|

| B.F. "Grimes" Davis Union cavalry officer who used his southern drawl to fool Confederate troops in the dark. |

One has to wonder about those remaining twelve thousand-plus Union troops who were meekly surrendered by their commander. Had they followed Davis across the pontoon bridge, would they have been been put to good use two days later at Antietam? Judging by the way we'll see how McClellan would use the overwhelming force he already had, probably not.

Anyway, Miles' surrender of Harper's Ferry came just in time for Lee and at the worst time for McClellan. For now the 26,000 Confederates that were used in its siege were free to head northwest to consolidate the whole ANV at Sharpsburg. While the Union victories at Crampton's and Turner's Gaps over South Mountain on the 14th had forced Lee to frantically withdraw his thinned out troops to Sharpsburg, McClellan, true to form and still far behind the lines, decided to rest his army once more and wait for supplies to come up. Li'l Mac was far more comfortable micromanaging logistics than leading combat operations. So he gave Lee an extra day to draw in his scattered army and set up his positions the high ground west of Antietam Creek.

Late on Monday the 15th, McClellan finally ordered his army to tentatively begin reconnoitering the Confederate positions around Sharpsburg, but would not authorize any aggressive moves. By the morning of the 16th he had a three-to-one superiority in place against Lee. But he yawned, put his feet up on his camp desk in front of Pry's farmhouse, and said there was time the next day to begin his assault. Lincoln had been sending him urgent messages after his report of the minor victories at the South Mountain gaps on the 14th, urging him to press on and destroy the disunited Rebel army. But the Young Napoleon apparently had no intention of doing so. As he wrote his wife, he felt his primary job was to persuade Lee to go back to Virginia, which, to him seemed to be happening, and to do so without any unpleasantness. So to him it was time to celebrate his great strategic victory. You just want to slap this incompetent, self-important little dip. Though he was reportedly popular among some of this troops, he was the worst possible commander at the nation's most critical time.

Lee, pretty nervous himself, was tensely awaiting the arrival of Jackson, McLaws, Walker and the rest of the commands who had just captured Harper's Ferry. Gradually those forces began to come up on the 15th and 16th. A.P. Hill's 3,600 men were still managing the captured 12,600 Federals and shipping off the captured stores (including Black people) south and wouldn't arrive until late on the 17th. But for the two days of McClellan's leisure, the Confederates grew stronger around Sharpsburg. By sunset on the 16th, though, they still numbered only around 30,000 to McClellan's 74,000.

And McClellan continued to do nothing. Based on his "gut", and on the horrible assessments provided by Pinkerton, his incompetent intelligence chief, and his refusal to use his own cavalry to feel out the enemy, he assumed that it was Lee who outnumbered him, by 100,000 men or more.

Lee, though probably biting his fingernails, knew his enemy. He knew that McClellan had never personally led in a battle himself, and that he was a coward, preferring to hang back, observing through "heavy lenses", to risk nothing, and retreat at the first check. The Confederate was counting on this posturing phony to act as he had in the Peninsula earlier that year.

What Lee didn't count on was the ferocity of the Union rank and file. After the Rebel victories in the first part of 1862, there was a confidence among the Southern troops that one of them could whip ten Yankees. But, as we'll see, this was to prove fatal overconfidence. The Bluecoats were itching for payback.

Not until the 17th, almost two days after Lee had built up his army and dug in, did McClellan issue orders to attack. His overall plan was for a double envelopment. Joe Hooker's First Corps (recently inherited from Burnside) and Mansfield's Twelfth Corps were supposed to cross the Antietam Creek via the Upper Bridge at Pry's Mill (see deployment map at the top of this post) and hit Lee's left from the north with their combined 17,000 men. Meanwhile, further south on the Antietam, Burnside,with his reinforced command of Ninth Corps (about 13,000) was supposed to rush over the Lower Bridge (then called the Rohrersville Bridge and later dubbed Burnside's Bridge) and roll up the Rebels from the opposite flank; a double envelopment. The rest of the army (Second, Fifth, Sixth Corps, the Cavalry, and most of the artillery— 42,000) was supposed to stay on the east side of the Antietam in reserve, awaiting events. Characteristically, though, McClellan only spoke of this strategy in the broadest, most abstract terms to his lieutenants, issuing no direct orders. He felt that his generals would know what to do and when.

He gave Hooker permission to take his First Corps over the river in the late afternoon of the 16th and set up for the next day's "surprise" enveloping attack. Hooker did this and exchanged a few skirmishing blows with John Bell Hood's Rebel division, then settled down for the night. All this did was alert Lee and Jackson to the "surprise" attack, giving them all night to swing forces into position on the threatened north flank and dig in for it. Honestly, I don't know what McClellan was thinking. Later that night Hooker's First Corps was followed by Mansfield's Twelfth Corps, almost as an afterthought. Compounding his ineptitude McClellan gave orders that no fires were to be lit as the troops bedded down, you know, so as not to give away his "surprise" (really?). As it started to rain, the troops spent a pretty miserable night.

The other bonehead thing McClellan did in preparation for his battle was to keep all his cavalry (under Pleasonton) bunched together on the east side of the Antietam, "in reserve". Evidently, the Young Napoleon thought this is what the Old Napoleon would've done (like at Waterloo, Borodino, or Eylau), regarding his cavalry as some kind of killer punch to be used at the climax of the battle—or something. By the middle of the 19th century cavalry, which had become vulnerable to long range artillery and rifle fire, had not been used this way for decades (except suicidally— see the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava, or my post about the end of the Battle of Cedar Mountain) and had evolved into primarily a reconnoitering, screening, and raiding arm. Neither McClellan nor Pleasonton used it this way, though. In fact, McClellan himself, seven years earlier, had actually personally witnessed the debacle of the Crimean War as a military attaché, including the misuse of cavalry, and even went on to write a cavalry manual—out of date before publication. So in holding his cavalry back, he prevented it from screening his own maneuvers and blinded himself to what his enemy was doing. Brilliant!

(Are you getting the impression that I don't like this guy?)

Evidently, in delaying his attack all during the 16th, McClellan hoped that Bobby Lee would take the opportunity to retreat. Instead Bobby used that opportunity to build up his forces as they marched up from Harper's Ferry. McClellan also evidently believed he was still outnumbered by Lee; that the Confederates had at least 100,000 men, three times what they in fact had.

The front lawn of this Pry Mansion was quite a convivial spot for a picnic and for McClellan to look across the stream and countryside. It was also quite out of range of any enemy artillery or cavalry raids. ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Panorama toward the battlefield from the hill behind the Pry House. This was on a clear day, without smoke or morning haze, so you can see very little out to the actual front from here.

©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Well...we might as well start the battle.

At 5:30 on the 17th Hooker, on his own initiative, still having no direct orders from McClellan to attack, started his offensive at dawn. Mansfield's Twelfth Corps was still in bivouac a mile to the rear of

Hooker's, having been up almost all night crossing the Antietam, so were just starting to brew coffee

when the battle started. On the Confederate side, during the wee hours, Jackson had reinforced Lee's northern wing partially behind hastily thrown-up breastworks from the dismantled fence rails along the Hagerstown Pike. And he sent out hundreds of skirmishers into the West and East Woods to harass the bivouacking Yankees.

Hooker had about 9,200 men and 43 guns in his First Corps, backed up by Mansfield's Corps with some 8,000 men with 38 guns. Not an overwhelming force against Lee's left flank, imagined by McClellan's gut to be as many as a million men, (actually a little over 15,000 with 74 guns). Moreover, Lee held interior lines while the Army of the Potomac was stretched out around a six mile arc, bisected by the Antietam Creek, further squandering McClellan's numerical advantage. The Young Napoleon's tactical plan couldn't have been worse.

Reprise of the map at the top of this post, so you won't have to scroll up. Isn't that considerate of me? This is the situation about half-an-hour after the beginning of Hooker's advance.

©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Hooker's primary objective at this time was a small, stone church (officially The German Baptist Church of the Brethren, but snarkily nicknamed by the less evangelical locals "the Dunkers" after their rite of full immersion baptism). The path of Hooker's first wave of attack was across a cornfield between the West Woods and the East Woods, hereafter called by it's generic "The Cornfield". None of these features had these names at the start of the battle; they were probably originally named for the lands' owners (Miller, Poffenberger, Morrison). But they all became the sites of such carnage that they were capitalized by historians and the National Park Service since.

| ||

| Dunker Church in 2001. Doesn't really look like a church, does it? Those German Baptists were real fundamentalists.©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 Digimarc protected | . |

Hooker's divisions under Ricketts and Doubleday launched their charge toward the Dunker Church through the Cornfield, Miller's meadow, and the West Woods in waves, only to be cut down by the Confederates waiting behind the makeshift barricades as they emerged from the rows of corn into the open. Rather than immediately retreating, though, they stood and returned fire. Both sides took terrible casualties, some of the highest rates in the war, until they ran out of ammunition and reluctantly withdrew, only to be replaced by supporting brigades. The Rebels' and Lee's cockiness that one Johnny Reb was worth ten Billy Yanks was quickly dispelled. These Yankees were tough sons-o-bitches and eager to give back on the humiliating losses of the Peninsula, Second Bull Run, Cedar Mountain, and the other defeats they had endured prior to Antietam (mostly due to the incompetence of their commanders, not to the cowardice of the soldiers).

One of the many waves of Union attacks toward the Dunker Church that morning

Salon painting by Thurle de Thulstrup, 1887

|

As if illustrating this rank-and-file resolve vs incompetent leadership, one brigade commander, Col. William H. Christian, lost his nerve and seemed to become deranged as he had his troops perform a series of parade-ground evolutions while under fire from Confederate artillery. Many were killed during this pointless ritual, and yet, under their company officers, the men closed ranks and did not break. But their commander did. Mumbling something about being unused to such carnage (though he was a long veteran of combat), he suddenly just started walking to the rear. He sadly ended up resigning his commission two days later. But I'm not judging. Considering all the years of combat he had endured, he probably just broke from PTSD. But his men didn't. They went forward and fought hard, killing as many as they were killed.

For about an hour Hooker's corps engaged in this mutual massacre. Hooker himself, unlike Christian (and especially unlike McClellan), rode back and forth along the thickest of the fighting, losing many staff officers, exposing himself to the slaughter, and ordering gaps plugged by reserves. However, because of McClellan's withholding of his cavalry behind the Antietam instead of deploying it as a screen, Hooker didn't have any knowledge of the enemy force on his own right (held by some of J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry and guns) and kept Meade's division in reserve and facing that way. So he was fighting against terrible odds with one hand tied behind his back. He sent urgent requests back to McClellan that he was "driving Lee" but needed Mansfield's Twelfth Corps (8,000 men) to come to his support. He got no replies. Since it was so early, it may have been that Li'l Mac, two miles away at the Pry House, was presumably still enjoying his croissants and latte ("Mmmm, you should try these, Pinky, they're delicious!"), but there is no record of him having ordered Mansfield to move up to support Hooker, or even of his ordering Burnside to move down to the South Bridge and begin his attack on Lee's right flank, nor of his ordering any of his reserve of 56,000 lounging around on the east side of the Antietam to get up. There were plenty of memoirs by his staff and reporters of easy-chairs being brought out to the front lawn of the Pry House for them all to enjoy the view. In spite of Hooker's flag signals and dispatch riders pleading for help, McClellan was heard to blithely say, "All goes well. Hooker is driving them."

On the Confederate side, Jackson was doing everything he could to keep the ANV's flank from caving. He pushed brigade after brigade to plug gaps and try to hold Hooker's attack in check. He barely did. The Rebs were taking as many casualties as they gave. These Yankees were not the pushovers that Lee and everybody had assumed. Both sides fought until their regiments were decimated and only withdrew when their ammunition ran out and they were relieved. It was a battle of attrition. The only tactical question was which would run out of men and bullets first.

Alexander Gardner's post-battle photography was considered almost obscene in its day; the true cost of war. The bloated bodies of Confederates— human beings, sons, brothers, fathers, husbands, friends— lying along the west fence of the Hagerstown Pike (to the right in this photo, not the farm trail to the left of them). Antietam was to become the bloodiest single day of American history (yes, including 9/11).

And this was just the beginning of that day.

About the climax of Hooker's drive at 6:30, reinforcements for Lee started arriving from Harper's Ferry. McLaws' and Richard Anderson's divisions, (about 7,200 and 34 guns together).After having marched all night, the column head showed up on the road west of Sharpsburg. They were most welcome. Also, since there didn't seem to be any Federal movement at all on the east bank of the Antietam, which would've threatened his right flank, Lee felt safe enough to request that Longstreet move one of his brigades (George T. Anderson's, not to be confused with George B. Anderson's—I know, too many Andersons in this army) over to the left to reinforce Jackson.

Jackson was indeed running out of resources. He started throwing in his last reserves. About 07:00 he ordered Hood's already depleted division resting in the West Woods to charge across the field east of the Dunker Church. Though Hooker's divisions had apparently captured this ground, these "fresh" Confederates (mostly Texans) threw them back across the Cornfield and East Woods until they themselves were stopped by Hooker's artillery and his own reserves from Meade's division. Then, in turn, Ripley's Georgians and North Carolinians attacked, throwing Meade's men back. And back and forth.

View from Hagerstown Pike across the Cornfield. Site of the back-and-forth carnage in the morning. Taken in 2001. Corn in Sept 1862 would've been higher.

©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

At around 07:20, Mansfield's Twelfth Corp began to show up and join the

fight, relieving Hooker's exhausted troops. Most of the soldiers of this

corps were green Pennsylvanians, less than a month in service, but

eager to fight. Mansfield himself, though a 40-year veteran had never

held a field command, or even had any combat experience since the Mexican-American War sixteen years earlier . This corps was his first —awarded just two days

before. McClellan had given him no direct orders to support Hooker, but he

took it upon himself (with Hooker's persuasion), to join the battle. No

sooner, though, had he begun to put his troops into line than he himself

was taken out by a shell fragment and evacuated to the rear (where he

died the next morning). Mansfield was replaced by the senior division

commander of the corps, Alpheus Williams, who had been acting corps

commander prior to Mansfield's promotion two days before.

Though rookies, and stiffened by the more veteran (but smaller regiments) of the corps, the Pennsylvanians pitched into the Confederates still hanging on in the Cornfield, the East Woods, and the fields between the Miller place and the Dunker Church. They paid dearly, but also slaughtered their foe in kind. Hood's, Ripley's, all of the survivors' of Jackson's resistance, were driven back beyond the Dunker Church.

Finally, Jackson, depleted of all reserves except for one brigade (Early's, now under William Smith positioned to the west to guard Stuart's batteries), had no resources left. Lee promised him McLaws' newly arrived division (but exhausted after having marched all night in the rain from Harper's Ferry). It didn't look good.

The hour-and-a-half battle for the Dunker Church had been so vicious that

both sides had suffered casualties not yet seen in this war, or any war

in the history of the United States. Some regiments on both sides were

completely wiped out. One regiment, the 6th Georgia, suffered 90%

casualties. Most engaged had 50% at least. And nearly everyone on both

sides had no more ammunition. It was apocalyptic.

But Hooker had by 7:30 finally achieved his initial object, the area around the Church at the junction of the Hagerstown Pike and the Smoketown Road. The next object was to drive in Lee's northern flank completely, cut off his retreat to Harper's Ferry, and force him to collapse and surrender, But Hooker's own forces were so exhausted and diminished that he needed reinforcements from McClellan's vast reserves to accomplish that. And he needed them before Lee could rally and regroup.

I'll leave you to guess what the Young Napoleon's response to this was.

Go on...take your time. He certainly did.

"Well...okay, I guess you can go. But leave one division here."

From their comfy perch back in their easy chairs on Pry's hill, McClellan and his staff couldn't make out clearly what was going on over at the Dunker's Church. The woods, the smoke from the burning buildings at Mumma's farm, and all the smoke from the battle were obscuring their telescopes. He had been heartened by Hooker's last message that he was "driving Lee". But, frankly, he couldn't very well make out the urgent flag signals that Hooker and Mansfield needed help (he didn't know that both had been wounded, Mansfield mortally).

|

| Edwin "Bull" Sumner, posing to look impetuous. Yes, he looks a little like Lee, to me, too. |

Apparently there was much speculation on McClellan's staff that by "driving Lee" Hooker had meant that he had driven him back across the Potomac, which would've suited McClellan beautifully. He had no wish for the unpleasantness of a battle of annihilation. The idea of even taking Lee at a moment of disadvantage was not what gentlemen indulged in. Let him go. And good riddance.

But finally, a little after 8:30, McClellan sent word to Sumner down by the Antietam that his corps had permission to cross and help Hooker. The Bull didn't need confirmation of this order and started at once. But as he was pushing his divisions across the stream, another messenger galloped down to tell him to leave one division of his three (Richardson's 1st ) back on the east side—in reserve—just in case. What if Lee's so-called retreat was merely a trap, luring the Union army into the jaws of the hidden hundreds of thousands of Rebels hiding behind the woods? Better to be prepared.

A better prepared general (says this armchair one) would've have used his abundant cavalry to reconnoiter and screen the enemy ahead of time, instead of holding them all back in a bandbox. A better prepared general would've used real time intelligence instead of just his gut. But then I used to be an intelligence officer so I'm just a little biased.

Pry's Ford, where Sumner's II Corps crossed the Antietam about 08:30.

©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

The Second Attempt

It took Sumner about an hour to wade his two divisions across the creek and lead Sedgwick's division the two miles (3.22 km) to the vicinity of the East Woods. On the way he ran into Hooker, who was being taken back to the field hospital, bleeding from a mangled foot and drifting in and out of consciousness; so he didn't get much information out of him. He finally reached the East Woods, where he met Alpheus Williams, the successor commander of Twelfth Corps (remember, Mansfield was mortally wounded), who tried to brief him on the stalemated situation. But "Bull" Sumner wasn't named that for nothing. He dismissed Williams as cowardly and incompetent, and wouldn't listen to his advice. Instead Sumner had the three of Sedgwick's brigades line up one behind another, thirty yards apart, stacked in one gigantic grand column (reminiscent of Ney's Grand Column at Waterloo). Then they moved majestically across the open ground of the Miller farm, into the West Woods. Sumner refused any advice from the officers and men who had been already fighting there all morning. He didn't seem interested in what enemy lay to the west or south, or what their dispositions were. Instead, he personally led Sedgwick's 3,600 men due west, right into a trap. Maybe McClellan's caution had been prescient after all.

During the hour's lull that had followed the first fighting in this sector, both sides had fallen back and taken a breather. Jackson, though having essentially lost the first round, didn't consider the game over. He rallied his broken regiments and fed fresh forces into the West Woods (well, as fresh as McClaws's could be after having marched all night in the rain and mud and without a rest stop.). He also had J.E.B. Stuart move all Pelham's artillery up on the ridge due west of the West Woods to rain down shot and shell on the approaching Grand Column of Sedgwick's division. Meanwhile, S.D.Lee's massed Confederate batteries south of the Dunker Church were perfectly positioned to enfilade the approaching Yankees from the south from 700 yards (640 m).

Sedgwick's troops, lined up so close, one brigade behind another, that they couldn't maneuver. They were also sitting ducks for artillery. They started taking horrendous casualties even before Sumner got them to the West Woods. And once inside those woods, they were attacked from the front and left flank by Confederate regiments lying in ambush. Because they were so tightly packed, they couldn't easily change front. Some regiments lost half their men without being able to fire a shot. Sedgwick himself was wounded five times.

It didn't take long for the Bull to realize his mistake. He frantically rode back to try and stop the next brigade of troops in the column, and to make them retreat. They thought he was rallying them (they couldn't hear him through the deafening explosions and fusillade of musketry), but he was actually trying to get them to fall back. When he got to the rear he sent messengers to Williams (whom he had disdained before) and to McClellan to send him reinforcements. In personally leading Sedgwick's division into the blind attack into the West Woods, he had left his following division under French far in the rear, still crossing the Pry Ford. So he lost touch with his own immediate supports.

After giving as much as they took, Sedgwick's division fell back with horrendous losses to the North Woods. Elements of Gorman's brigade (1st MN, 82nd NY, and 19th MA) held on at the north end of the West Woods but most of those woods were still in the possession of the Confederates by 9:30.

At the south end of Miller's field, around the Dunker Church, the fighting continued back and forth until the early afternoon, with counterattacks back and forth by Greene's Union division and waves of Confederates. In the end, both sides had endured horrendous casualties and the open ground and the Cornfield were carpeted with dead and wounded Americans. By late morning Southern forces held the West Woods and the Northerners the East Woods, and nobody held the middle. It was a bloody standoff.

"Bees!? Now bees?! Are you kidding me?!"

Shortly after Sedgwick's disastrous attack and retreat, Sumner's Third Division under William French (called "Old Blinky" by his men for a facial tick he had when he spoke) arrived somewhat southwest of all this action around the Cornfield. Having no communication with his division commander, Bull Sumner, who had galloped ahead to take part personally in the first, blind attack, French veered southward over the ridgeline north of the Mumma Farm. Here he spotted a target of opportunity along a line formed by a sunken road between the Hagerstown Pike and the Boonesboro Pike. This sunken road would be later called "Bloody Lane" by the participants (and the National Park Service). A pretty literal epithet. But it was, during that day, just referred to as "The Sunken Road".

During the lull between the first Union attacks on the Dunker Church and this second wave, Longstreet and Lee, who had been nervous of an enveloping assault from the south across the Rohrbach Bridge, observed that there seemed to be no movement down there. Burnside's/Cox's Ninth Federal Corps all seemed to be just enjoying their morning coffee and making no moves to cross. In fact, McClellan had sent no orders so far that morning for Burnside to cross the bridge. Likewise, there didn't seem to be any movement by the Yankees across the Middle Bridge from the Boonesboro Pike. Lee knew his enemy, and having fought McClellan so many times before, knew that he was timid and could only focus on one thing at a time. So he and Longstreet concurred that it was safe to temporarily move the forces they had on the southern flank up to the center to absorb the Union attacks on that front. So Longstreet started doing that about 07:00.

Panorama of the view from the observation tower at the east end of Bloody Lane at the Antietam National Battlefield Park. ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Longstreet lined up D.H.Hill's division in the natural trench of that sunken road. They enhanced the position by dismantling the snake fence on both sides and piled up the planks into a breastwork. About 09:00 By the time they saw the first flags of the Union regiments pop up on the ridgeline above them, they were ready. Their officers passed the word to wait for it...wait for it....wa-a-a-a-it for it.

The first of those Yankees (1st DE, 5th MD, 4th NY, all new recruits of Weber's brigade) got within 80 yards of the sunken road, the sword came down. The Rebels, having propped their muzzles on their breastworks to take careful aim, let 'er rip. Fire and smoke rippled down the whole line. It seemed like the whole first rank of bluecoats went down. These were also pounded from H.P. Jones' batteries about 600 yards on the hill at Piper's farm to the south. The advancing line of Weber's brigade stopped and tried to return fire. But they were standing upright in the open and the Confederates were below them, behind cover. It was not a fair fight. Within five minutes Weber's brigade, which had begun the battle with 1,670 men, had lost 450 (over a quarter of their strength--so you don't have to do the math). They retired back over the cover of the hill where they came from. To the credit of these inexperienced Yankees, though, they didn't flee the field but knelt or lay down just behind the ridgeline to continue the firefight. They may have been raw recruits but they were brave. And tough. And every one was worth at least one Johnny Reb. So there.

Three-sixty degree panorama POV of what French's troops could see as they approached the Sunken Road from the north. ©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Right behind this first wave French's second brigade, another 1,800 raw recruits under Dwight Morris, marched up and over the firing line of Weber's men and down toward the sunken road. Eyewitnesses from the Confederate side remembered seeing just the tips of the regimental flags first rising above the ridgeline, and were able to judge by how new and pristine they were that the regiments following them were also raw. This detail was passed up and down the line and seemed to reassure the greycoats that this was just another gang of shop clerks and city boys; nothing to worry about. It'll be fine.

As soon as Morris's brigade came into view at the top of the ridge, they came under the same fire from the entrenched Rebs and started falling like flies, or nine-pins, or wheat from a scythe, or weeds from a weed-wacker, or dominoes, or some other clichéd simile...in other words; a lot. As they stomped down the slope, they were also getting hit from behind by friendly fire from Weber's men, who were firing blindly (literally...many were so inexperienced and stressed they were closing their eyes and turning their heads while they pulled the trigger). Morris's men tried to move forward, stopping to fire, but soon started backing up the hill to join Weber's crouching line. Some had had enough and bolted right over their own firing line and into the Mumma's cornfield behind the hill.

Longstreet, observing this from his position at the Piper farm, a few hundred yards to the south, sent orders to Hill to counter-charge the Yankees up the hill, which Anderson's brigade at least tried. But as they started up out of their trench, they were met with withering fire from the top of the hill and enfiladed by Federal batteries about 450 yards to the northwest. So they lost even more men needlessly and the survivors scrambled back.

Now the third wave if Yanks showed up, Kimball's brigade with the 14th IN, 8th OH, 132nd PA, and 7th WV. Except for the Pennsylvania regiment, Kimball's was French's only set of veteran troops. In fact, these had actually whipped Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley campaign seven months before. This time the Confederates noticed the more tattered flags poking up over the hill and recognized them as experienced killers. Hill's men were getting a little tired, and their rifles a little hot and fouled. But they kept firing. They had an efficient system in which the first rank would aim and fire and the second would reload and pass the musket forward in a cycle of teamwork. This increased the rate and accuracy of fire and preserved everyone's strength.

Kimball's brigade met the same fate as the first two and had to retire behind the ridgeline. During this third charge, though, a funny thing happened (well funny but for all the blood and guts and death). A stray cannon shot knocked over a row of beehives next to the orchard by the Clipp farm and angry bees swarmed the Federals, chasing them back a few hundred yards. After some time, though, the bees gradually calmed down and the men slowly rallied at the ridgeline to resume their firefight. They didn't sign up for bees! I'm sure the bees were thinking the same thing about humans.

During these three charges, though the Confederates held their own, they were also taking horrific casualties, not just from the rifle fire from front (in spite of their cover) but from both flanks. From the west, Tompkins' and Monroe's ten Federal guns were able to send shot and shell right down the length of the sunken road from close range (450-650 yards—okay, 411.18-594.36 metres, for my international readers), wreaking horrible carnage. And from the east, less than a mile (1.6 km) across the Antietam (but still within range of Civil War era artillery), as many as 20 rifled guns were able to shoot right up the Sunken Road, turning the ditch into a giant food processor. Hence the later nickname, Bloody Lane. And hence one of the nicknames veterans gave for the Battle of Antietam, "Artillery Hell".

So while Hill's men held, it was only a question of time how long before they were all minced. (Sorry...I meant "passed away". Is that a more sensitive phrase?)

Capt. James Hope's painting of The Aftermath of Bloody Lane, and all the passed away, c. 1870-ish

Another reason this battle has been nicknamed "Artillery Hell".

|

Unlike McClellan, Lee had been very active in moving all over the battlefield, ordering up reserves, redeploying artillery, rallying retreating regiments, and plugging holes. He had ordered up Dick Anderson's newly arrived division to rush through Sharpsburg over to reinforce Hill's hard-pressed men in the Bloody Lane. Unfortunately, before he could get to the front, Anderson himself was shot off his horse by a random canister bullet and severely wounded in leading this advance through Piper's cornfield, leaving his senior brigadier, Roger Pryor, in command of the whole division. Pryor himself was getting lost in the confusion and had not been made aware of Anderson's wounding and that he was in charge. Consequently, the succeeding brigades of the division got all tangled with each other in advancing. The only one that made it to the sunken road at first was Wright's 459 men.

Situation map for 0930, the crisis point for the Confederate center

©Jeffery P.Berry Trust 2023 protected by Digimarc digital watermark.

Around the same time, the rest of Dick Anderson's (that's Richard, as opposed to George B.... C'mon! Keep up!) "relieving" brigades began to make their way out of Henry Piper's cornfield and pile into the Sunken Road to join D.H.Hill's men, already packed like sardines in the confined gully. This overcrowding didn't help. The men were so crowded and intermixed with "relieving" regiments they were having trouble maintaining their previously efficient method of reloading and firing in pairs. And nobody knew who was in charge.

In twos and threes and eventually in whole companies, the jammed mob of out-flanked Confederates started climbing back out of the trench to run back through the cornfield toward Piper's farm.

Seeing this trickle and then the sequential retrograde movement as a sign the enemy was on the verge of collapse, Col. Joseph Barnes, the enterprising CO of the 29th Massachusetts (the only non-Irish regiment in Meagher's Brigade), jumped up and shouted for his men to follow him in a charge down the hill. Always irritated by the obnoxious, high-pitched squeal of the "Rebel Yell" they had been subjected to in so many battles, Barnes exhorted his men to yell in their own way to scare "the bloody bastards" (an Irish term of endearment). This noisy charge from a foe they had assumed defeated triggered general panic among the confused and outflanked Confederates packed in the Sunken Road, ("Hey! We're the ones who do the shrill yelling!"). Soon, one by one, other frustrated and pinned down Union regiments jumped up to join the 29th's charge and rush down the hill. Joining the yip-yip-yip.

Just before Barnes' attack, Confederate Gen. Rodes, noticing that Caldwell's Yankees were outflanking his line from the east, rode up and ordered the CO of the 6th Alabama have a few companies redeploy right and return fire at the Yankees. Apparently, Lt.Col. Lightfoot, the regiment's commander, misunderstood the order in all the confusion and instead, ordered the whole battalion to about-face and retreat to the rear (huh?). His neighboring regimental CO asked him if retreat were a general order for the whole brigade, and Lightfoot said, yeah. So the previous trickle of ones and twos inadvertently became a general rout as one after another Confederate regiments clambered out of the Sunken Road and ran across the cornfield back to the Piper farm.

|

| Alexander Gardner's photo of "Bloody Lane" the day after the battle. |

Back at the Confederate massed batteries of H.P.Jones around Piper's farm behind the Sunken Road, they were now frustrated by the crowd of fleeing friendlies heading toward them and didn't dare fire at the pursuing Yankees behind and among them, Whether by design or luck, the Federals used the Confederate panic to their own advantage. And the Sunken Road, this bastion of Lee's center, collapsed.

But the Yankees who had been equally fighting and dying all morning were also spent by this time (about noon), most regiments having lost close to half their strength. Rather than chasing the routed Confederates all the way to the Potomac, Richardson and French halted the pursuit. They weren't sure if there weren't more Rebs lurking over the ridge between them and Sharpsburg, and, to be fair, there were several forlorn hope counter-attacks by small crowds of Rebels for the next couple of hours. So what was left of Richardson's and French's divisions fell back to regroup in the Sunken Road.

To the northwest, after Hood's attack across the Cornfield earlier had petered out, George Greene of the Federal Twelfth Corps, took two brigades of his division and charged out of the East Woods, driving all the Confederates still in the field, past the Dunker Church and into the West Woods. Greene then settled into defensive positions in the West Woods around the church for the rest of the morning. It was the farthest penetration of Lee's line so far. And Hooker's original objective, the little church, was finally achieved.

As the afternoon began, there was a lull in the fighting. It seemed as if both sides were taking a deep breath.

"Retreat, Hell!"

You might've thought this already horrific morning would have spelled the end for Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, or even for the Confederacy. After all, Lee's center and left had given way and were seeming to fall back toward the Potomac. You might've thought McClellan would've taken the opportunity to order a general attack along the whole front with his vastly superior force, three fresh corps (Fifth,Sixth, Ninth, and all the cavalry) 41,000 troops waiting for orders on the other side of the Antietam.

You might've thought. But, of course, McClellan wasn't close to the front or in touch enough to know what was going on in the center, or how close Lee's army was to collapse. The Pry House, McClellan's headquarters, was too far from the action and, besides, though he was high on a hill, his view was obscured by trees and smoke. Unlike Lee, he didn't think it necessary to go to where the fighting was to find out what was happening himself, or to rally his troops. That would've been too dangerous. Besides, listening to the opinion of his incompetent intelligence officer, Pinkerton, and not using his cavalry for reconnaissance, he was still believing that Lee was concealing his main strength in waiting (like maybe a few million more angry bees?). It would've been just what his sly Virginian nemesis would've wanted Li'l Mac to do: attack across the whole length of the Antietam, right into a trap.

"Hah! Nice try, Bobby! I'm not falling for that!"

So, the fighting on the north side of the battlefield just went on, back and forth, neither side gaining any ground but just grinding each other up senselessly. By 10:00 over 8,000 Americans had killed or wounded each other. And the slaughter was just beginning. Even taking account of the fact that the United States in 1862 had one-tenth the population it has today, that number is staggering; the proportional demographic equivalent of 80,000 casualties in 2023. In four hours! And the Confederates didn't even have machine guns, or drones, or modern artillery or hijacked planes to crash into skyscrapers.

Except for a few limp feints, from about 12:00 on the fighting on the northern and middle sectors of the battlefield had settled down to sporadic skirmish fire and artillery barrages. Both sides were exhausted. McClellan had yet to visit the front to see for himself. When he sent an order for Sumner to renew his attack, Sumner yelled at the messenger, "Go back, young man, and tell General McClellan I have no command!"