American Revolution

3 January 1777

Americans: George Washington, ~4,000 with 10 guns

British: Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood ~1,000 with 12guns

Weather: Rain and mud on the 2nd, melting the Christmas snow that had fallen the week before. The weather turned freezing the night of the 3rd, which hardened the ground and roads. Day bright and sunny.

Dawn Twilight: 6:52 Sunrise: 7:22 Sunset: 16:46 End Twilight: 17:16: Moonrise: 0:21 waning crescent

(calculated from U.S.Naval Observatory site)

This is the follow-on to my previous article on the Battle of Trenton, eight days before. And this one proved to be the decisive battle that really cemented the American survival in the early months of the Revolution. The British command up in New York City seemed to have dismissed Trenton as a fluke. After all, to them it was nothing but a glorified raid, a hit-n-run ambush--and on a drunken bunch of German mercenaries at that! (which turned out to be a complete slander, and not true.) But Washington's victory at Princeton a little over a week later was undeniably no-such fluke, beating British regulars in a stand-up fight. It showed the brothers Howe, the joint British commanders-in-chiefs in America, as well as to the Tory government in England and the king himself that the Americans were more formidable opponents than they thought. It would take some time to knock them into submission. This turning point reminds me of Czar Vladimir I's gross miscalculation of the Ukrainian resistance to his invasion of that former Russian colony in 2022—for much the same reasons that King George used to subjugate his former colonies in America—that it was a traditional part of the old empire and needed to be yanked back under imperial control.

Not that history repeats itself, of course. I'd never say that.

But before I start, I want to dedicate this post to my old friends and fellow history nuts, Tom and Karen Smith. Together we toured the Princeton battlefield and Washington's Crossing Sit several years ago. It was a memorable day and I have long wanted to write posts about this battle and Trenton. Done.

First Phase of the Battle, as Mawhood is alerted to the Americans marching up toward Princeton to his southeast and doubles back to check them at Clarke's farm, where Mercer's and Cadwalader's brigades intercept him in a vicious fight. Ooops! Should've given a spoiler alert.

take this sitting down

cancel his voyage home and to head south to Princeton to take charge of the British forces in New Jersey and eradicate Washington's ragtags once and for all.

|

| Morven House in Princeton, Cornwallis's HQ photo from Google Street View by Henry Singer |

|

| Cadwalader's hand-drawn map of Princeton and its defenses given to Washington on the 1st. To see a more hi-res version of this, go to Plan of Princeton, Dec.31 1776 |

Charlie Brown

football she holds. Every time Charlie Brown always declines, knowing that she will whip the ball out just as he runs up to kick and he'll fall on his butt. But every time she assures him that this time she won't do that, and every time he falls for it. Well, this is what Cornwallis falls for. Though he has been fooled before by Washington at Brooklyn, when the Virginian snuck away during the night by having a rear guard keep fires lit and making a lot of noise, he has no idea that Washington is going to do it again.

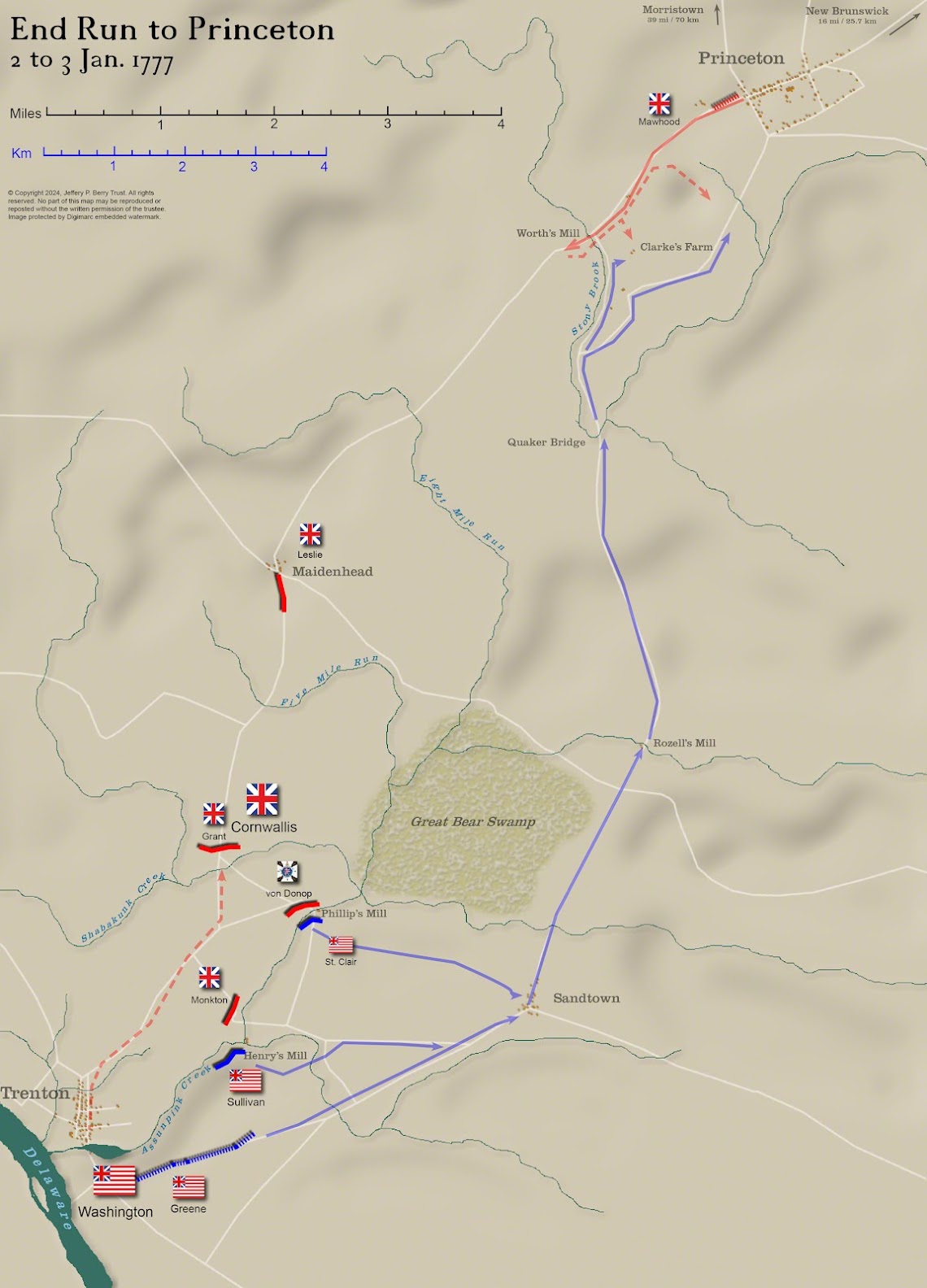

Washington slips away from the Assunpink Creek starting at 22:00 the night of the 2nd and moves northeast toward Princeton, fooling Cornwallis again.

Whoa! Where did they come from?

|

| Snowy track next to Stony Brook photo from Google Maps, by Ronald Peterson |

But the unexpected happened. Just after dawn, responding to orders from Cornwallis, Lt.Col Mawhood, the British garrison commander at Princeton had set out himself with part of his brigade to bring supplies to Trenton. He was marching southwest down the main Post Road with two of his regiments, the 17th and the 55th, as well as some replacement troops for the 42nd, a grenadier company, a light company, about 100 cavalry, and some cats-n-dogs (literally, he had his two beloved springer spaniels with him—I don't know if there were any cats, though). As this column started to cross the main bridge over the Stony Brook at Worth's Mill, a trooper from his flanking light dragoon regiment (16th) came galloping up and told him that they had spotted a large column of enemy troops to the southeast, marching up toward Princeton.

|

| View of Stony Brook today, but shot also taken in January. from Google Street View, photo by Pete Luzzo |

Mawhood immediately halted and ordered his column to about-face and march back across the bridge. He sent word back to Princeton to alert the 40th Foot, which he had left there to guard the magazines. He ordered the 55th to go back to a hill to the southeast of the town and set up a defensive position there (scroll to first main battle map at the top of this post). With the remainder of his force (17th, 42nd, the cavalry, grenadiers, light infantry and the dogs—but maybe no cats) he turned south to attack the Americans he spotted coming up toward the Post Road at William Clarke's farm.

On the American side, they were just as surprised to see all the Redcoats to the north of them. Brig.Gen. Hugh Mercer, in command of one of Greene's brigades, was originally supposed to head up to the main bridge on the Post Road and dismantle it, followed by the rest of Greene's troops (the brigades of Cadwalader, Mifflin, and Fermoy) who were then supposed to turn right and assault Princeton down the main highway. But Mercer saw, to his shock, a line of red uniforms coming right at him.

Mercer quickly raced over to the apple orchard behind William Clarke's farmhouse and deployed his 350 men and two guns under Capt. Neil. Mawhood's men, meanwhile, deployed across the fence north of the farmhouse, about 300 yards north of the orchard. Laying their muskets on the rails to steady their aim, the British fired first. But they overcompensated for the range (which the effective for a Brown Bess musket was, at best, 100 yards) and their shots went high, clipping some apples but hitting no Rebels. They then started moving forward, supported by their own two 3-pounder guns and light troops, stopping to fire periodically.

|

Redcoat re-enactors at Princeton Battlefield State Park in 2023. Photoshopped to make the ground look snowy. What? What? Image from Google Street Viewby Randall Krakauer 2023 |

The Americans started firing back. Many were armed with rifles, which had a greater effective range, (about 350 yards), but a much slower rate of fire. They also had two 3-pounder guns (Neil's battery) firing canister from the left of the orchard. Soon both sides were taking casualties. But the British were undeterred and kept coming on. Their muskets were fixed with bayonets, which the Americans didn't have at this stage of the war. As the Redcoats came within 50 yards, they yelled and launched into a running charge, bayonets lowered. Close combat is where the Americans were at a terrible disadvantage. Only able to club back with their rifle butts, they quickly broke as the British started to stab them. They fled back toward the Saw Mill Road and Thomas Clarke's house. Gen. Mercer tried to rally his men but when some grenadiers demanded he surrender, he refused and was stabbed himself, falling under an oak tree. His executive officer, Col. Haslett, also refused to surrender and was shot dead in the brain. Several Redcoats repeatedly stabbed both Mercer and Haslett as they passed their prostrate bodies. Neil and his crew, firing their two 3-pounders to the last, were overrun and killed and the guns captured.

Mercer's Oak, which stood near the spot on which he got skewered, looking south toward the Thomas Clarke farm house (William's brother; William's farm and orchard are no longer there).. This is a younger tree, grown from an acorn of the original, which had died of old age in 1981.

Shot taken during a recent snow, which probably looked like it did the day of the battle in 1777. Image from New Jersey State Park Service, Princeton Battlefield Park)

Cadwalader, coming up behind Mercer's brigade with his Philadelphia militia, started to deploy his battalions. But the fleeing Continentals made this difficult. Mawhood halted his Redcoats, reformed them and started advancing again, this time toward Cadwalader. The Philadelphia militia, who were only recently mustered and with minimal training, had never been in combat. Some fired wildly but hit nothing. To their left, Capt. Joseph Moulder, unlimbered his three 4-pounders and began firing into the advancing British. This gave Cadwalader a steady anchor on which to rally his wavering regiments. Some of Mercer's men stopped running and reformed themselves behind Moulder's guns.

But the British kept coming, firing controlled volleys as they did. The Philadelphia men, and what was left of Mercer's, started to waver. Some ran. Cadwalader didn't know how long he could hold the line. The battle seemed lost fifteen minutes after it had begun. They had fallen back to just in front of the Thomas Clarke's farm behind the Saw Mill Road. He was sure this was to be the site of his last stand.

The death of Gen. Mercer by John Trumbull, 1831. He's got Washington center stage, who wasn't there in time to see Mercer bayoneted, or Capt Neil (to the left). The "Betsy Ross" flags are also wrong (hadn't been designed yet). So are the British regimental flags. And there was probably snow on the ground. Otherwise it's fairly accurate. There's Mercer's Oak, for example.

Then came Washington.

Just when everything seemed to be falling apart, Washington came galloping up. He had been with Sullivan's division, marching up the Saw Mill Road when he heard the gunfire behind him. Grabbing the rearmost brigade of the column (Hitchcock's, now Angell's) he rode directly in front of the wavering line of Cadawalader's troops, waved his hat, and shouted, "Parade with us, my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy and we will have them!" Bullets were flying all around him but he seemed heedless. His fearlessness, especially for one who throughout history has been likened to a behind-the-lines, bookish commander like Eisenhower or Grant, was completely out of character. But it infected the shaky troops with sudden, renewed courage.

|

| Thomas Clarke's house. Twice as large today as it was in 1777. photo by JS (GoGoJoe) 2024 on Google Maps |

That and the sudden appearance of reinforcements from Angell's brigade on their right and Fermoy's and Mifflin's on their left. Those helped too. The whole American army seemed to roll forward, enveloping the British, who had shot their bolt and found themselves hopelessly outnumbered.

Now the tide turned. In small, isolated groups, the Redcoats ran. The last of which was Col. Mawhood (and, I hope, his two dogs). They were chased all the way back to the main Post Road and beyond. Many surrendered. But many, led by Mawhood, also managed to bolt over the fields and make it beyond Princeton. They couldn't flee south over the Stony Brook bridge because about a 100 of Fermoy's men and another couple of cannon had blocked that avenue of escape.

To the northeast, the 55th Regiment (only 116 men) which had been posted on a wooded hill witnessed the whole see-saw battle. They noticed the overwhelming column of Sullivan's division below them and thought discretion was the better part of valor. When they saw the main part of the British line break and run, they discreetly retreated back through Princeton, pausing first to escort the guns behind the redoubts in front of the town back through the main street and on to New Brunswick.

Second phase of the battle. Washington gallops back to rally Cadwalader's and Mercer's men, bringing Angell's brigade with him. Mifflin's

and part of Fermoy's men hit the Brits from the west while some

run up to the Stony Brook bridge to start dismantling it, cutting off Mawhood's retreat toward Trenton or any reinforcements coming from the south. Meanwhile, the

rest of Sullivan's division presses over the Frog Hollow and persuades

the 4oth Foot to retreat into Princeton. The whole British force

collapses and either escapes or surrenders.

From Princeton itself, the 40th Foot's lookouts had reported the advance of Sullivan's division toward town so they immediately marched out to meet them. They first set up a blocking position at the ford over the gully known as Frog Hollow. But when Sullivan's brigades came up, they easily outflanked the 40th, as Alexander Hamilton's two guns pounded them from the high ground to the south. Evidence of the defeat of the rest of Mawhood's force got to the 40th in minutes, so, outnumbered and outflanked, they too withdrew back into town. A couple of hundred took refuge inside Nassau Hall. There they intended to make a stand, breaking windows and barricading the doors. But soon Sullivan's troops surrounded the building and called for them to surrender. They refused at first. Hamilton rolled his guns up close to the walls and began firing roundshot into the building. It is said that one of these slammed right through a portrait of King George (II or III, not sure), taking off his head. At that point a white flag was seen waving out of one of the broken windows. All two-hundred Redcoats were taken prisoner.

By 09:00, after a little over an hour, the entire battle was done. Washington rode into Princeton and ordered Sullivan to get control of his men, who were indulging in an orgy of looting. It seems American soldiers were no more civilized with their own countrymen than the British (the rationalization was that Princeton was reputed to be a Tory town). though there were no stories of apparent rape. But Sullivan and Washington together soon got the looting and mayhem to stop.

Who lost what?

The British had lost some 232 casualties of their original 1,000, though this figure is disputed. Cornwallis reported 18 killed and 58 wounded (76 casualties) and 200 "missing". Michael Stephenson, in his book, reports 101 killed and wounded from the 17th Foot alone. Washington's report to Congress was 100 British killed, 70 wounded, and 280 captured. Mawhood was not one of the captured or killed but managed to escape and reform the balance of his brigade after the Americans moved on from Princeton. I could not find if he was able to rescue his two spaniels (I hope so). But he was later rewarded by the king for his brave stand against overwhelming odds. He went on to fight throughout the Revolution and was eventually posted to Gibraltar in 1780 where he died, sadly, of a gall stone. Which seems a little unfair.

|

| Site of Moulder's battery which wreaked such havoc on the advancing British. photo from Google Maps by Mark Deavult Nov 2017 |

Washington reported all this to Congress but did not report the huge quantities of stores (including new shoes, blankets, ammunition) found in Princeton. He didn't want Congress, even then noted for its stinginess, to have an excuse to cut back on the funding of the war effort.

Caveat supectum But even historical accounts of casualties should be held suspicious. As with this little battle, so many others throughout history, right up to the accounting reported by Hamas to the UN (which the UN accepts apparently without question) and the IDF in the current Gaza war, are to be taken with a truckload of salt (this article in The Atlantic about casualty reports from Gaza is telling). Both sides in every conflict have propaganda motivations, and when casualties include innocents, those can be wildly inflated or deflated depending on who's doing the reporting. So with the casualty reports of this obscure battle in history. Also, the estimates for this old, small battle don't include any innocent civilian casualties in the surrounding farms and in Princeton (remember the citizens evicted into the freezing night from their homes by the British? and the looting by the Americans on suspected Tory houses?). The truth is that warfare entails destruction, brutality, sadism, and mass murder, often of the innocent. Always has, even in the "civilized" 18th century. It is a horrible business. And though I have long been fascinated with military history, every so often it occurs to me how dark my hobby is.

Okay...sorry for the digression. Where were we?

Where to now, General W?

The commander-in-chief could not afford to linger in Princeton. He knew that Cornwallis would've realized he had been Charlie Browned and would have heard the rumbling of battle up at Princeton. He'd be marching north with his whole army in a matter of hours. Washington had ordered that the bridges over the Stony Brook be destroyed (they were wooden, not like the new stone ones today) to delay the British. He had wanted to move on to New Brunswick where he could sack the main British magazines there and also seize the reputed cache of £70,000 the British had to fund their payroll (an equivalent of about $27 million today—or $27 billion if you figure in the price of eggs).

But Washington also recognized that his army was about to come apart. Weeks of forced marches and battles, not to mention that he had to bribe them to stay on another month past their expiration date,had almost completely worn out his men. He couldn't go south into the arms of Cornwallis's full force. He couldn't go back to McKonkey's Ferry to recross the Delaware again (it was uncrossable by now). And he couldn't expect them to march the 18 miles up to New Brunswick to fight another battle. Nor did he want to face Cornwallis's force of 8,000 who were expected to arrive any minute. In fact, hearing gunfire to the south at about 10:00, he realized that the British vanguard was already shooting at the men he had stationed at the wrecked Stony Brook bridge. His only option was to escape up into the mountains around Morristown in western New Jersey, 39 miles (70 km) to the north, where his army could rest, refit, and easily defend itself for the rest of the winter.

For the British, they also couldn't afford to chase Washington. As Cornwallis sent word to Howe that he had recaptured Princeton but that Washington had slipped through his fingers, Howe sent him a recall order to move the whole magilla back to New York City for the winter and start the campaign again in the spring. The British generals rationalized that the two defeats at Trenton and Princeton were really inconsequential in the long run. They told themselves and the king that these "battles" had been flukes, and, besides, fought unfairly. I guess they thought only the British were allowed to pull fast ones on their enemies. What the Howe bros, Lord North, the Tories in Parliament, and the king didn't realize was that this series of unfortunate events would give the American cause just the catalyst it needed to keep up the fight...for another six years. They also would give the Whig party in Parliament more leverage to oppose the costly war and grant American independence. And they would give Ben Franklin and then John Adams, Congress's ambassadors to France and the Netherlands, extra cards to play in winning over Louis XVI's and Dutch material support against their countries' nemesis.

360° panorama I took of the battlefield from the front of the Thomas Clarke house in 2008 at the position of Moulder's battery. Obviously a bright, sunny, summer day. Not the view on a frozen January 231 years before. Image from personal collection.

Armchair General Section

Even though the Battle of Princeton was an accidental encounter, it is hard to assign any mistakes to either side. Washington's end run around Cornwallis up to Princeton was done masterfully, completely fooling the British general. It was a model of misdirection and strategic coup, very much like Alexander the Great's coups-de-main at the Granicus and the Jhelum over two millennia before. As I've written in my previous post on Trenton, I would not have been surprised if Washington had not read Arrian or Plutarch, though evidently his early education was pretty basic (he never went to college, for instance).

Tactically, his deployment of his two divisions, adeptly countered the attacks by Mawhood. Though there was an initial setback on the part of the collapse of Mercer's brigade, the rallying efforts by Cadwalader and then Washington in person shored up that hole and turned the tables on the British force.

Mawhood, for his part, did everything a professional soldier could do under the circumstances. Though he was completely surprised by the discovery of the American army on his flank, he didn't panic. He coolly deployed his limited forces quickly and executed, at first, a devastating counterattack. In retrospect, the only alternative he had was to fall back rapidly on Princeton and defend it from behind its earthworks and stone houses. This might have worked long enough for Cornwallis to come up later that day. As it was, Washington had to vacate the town by late morning anyway as the first elements of the main British army began to reach the Stony Brook crossing. So that might have been an error on Mawhood's part.

|

| Monument to Gen. Mercer in front of the Thomas Clarke house, where he died of his wounds nine days later. |

Mostly, though, Trenton and Princeton served as political victories for the newborn United States. Though small, they demonstrated to any wavering Americans that the invincible British Empire could be vinced after all, and that there was a real possibility that they could actually win this war . They also showed King George that this "military operation" was going to be costly and not so easily won as he had thought. So there.

Wargaming Considerations

Anybody wargaming Princeton needs to take into account these factors:

- Bayonets The British regulars were armed with bayonets on their muskets. At this stage in the war, most American troops, Continentals and militia, had no bayonets and were at a great disadvantage in hand-to-hand fighting. In any rules involving close combat, you should give the British player a significant advantage. This would also affect the relative morale of either side.

- Fatigue The Americans had been marching all night, in freezing weather. While most had been reshod from their boon at capturing Trenton the previous week, it would've been a grueling 12 mile march in darkness, picking their way along small trails. So by dawn on the 3rd, as they crossed the Stony Brook, they were probably pretty well bonked.

The British in Princeton, by contrast, would've had a pretty restful night, roasting marshmallows around the campfires made from the locals' fences and church pews. So when they started marching out of town that morning, they would've been well rested.

Consequently, one should rate the Americans as fatigued in whatever wargame rules you are using, and the British as at 100%. - Morale The British were surprised. Though they hadn't been rousted out of their beds as the Hessians had been at Trenton the week before, the were certainly not expecting a sizable American force on their flank as they started their hike down the Post Road. The nasty shock of Trenton was probably very much on the minds of the British troops as they looked to the southeast and said to each other, "Oy! What's that?"

On the American side, they were probably feeling pretty smug after their victory at Trenton, and after they had so severely smothered the failed British attempt to force the Assunpink the day before.

So subtract a point or two from the British for nasty surprise on their morale factor. And give the Americans a point for still feeling the surge of victory.

Experimental Premises of Princeton could explore the following:

- Mawhood was still in town. If Mawhood had not begun his march out of town that morning, but had been alerted to the approach of Washington, would he have been able to effectively defend the town from the existing earthworks (see map) and stone buildings? Such a scenario could give Cornwallis four hours to show up with a relieving force (rolling for that every turn after, say, 10:00).

- Bayonets again If the American side (the Continentals at least) were equipped with bayonets, would that have evened the odds in the hand-to-hand combat around the Clarke farm?

- British intelligence What would've been the outcome if Cornwallis had been made aware of Washington's giving him the slip earlier the night before? Would the American side be able to out march him and burn the bridges to Princeton ahead of him and set up another defense at the Stony Brook?

Orders of Battle

The following OOB lists were compiled primarily from the David Bonk's Osprey book, Trenton and Princeton 1776-77. The units only include those actually participating in the battle.Command, besides listing the name of each command, this cell is also color-coded for the primary uniform coat color of the regiment. For the American troops, this color coding is mostly speculative since so many had essentially civilian coats, or brown coats, and those extremely tattered by this stage of the war. Nearly all of the New England soldiers were wearing brown coats, except for the Rhode Islanders, who mostly wore white buckskin), so reflected here.

Facing is color-coded in the facings of the regiment (e.g. cuffs, lapels, etc.). As with the coat color, where I could not find a reference, I assigned the default red facing.

Flags displays miniatures of the flags carried into battle by the units. Again, where I could not find a specific reference, I would leave this blank or use the default Continental Flag of the New England regiments (pine tree on a red field). Do not use this as a scholarly source, though.

Strength The strength reported by each unit on its roster on 22 Dec, as listed in Bonk's OOB.

|

| My old friends and fellow history nuts, Tom and Karen Smith, in front of the Thomas Clarke house in 2008. A memorable day for me. We also visited the Institute for Advanced Study only about 700 yards northeast of this, where Einstein spent his remaining years. And also the site of the 1938 Martian Invasion at Grover's Mill about six miles from here. Not to mention the site of Washington's crossing the Delaware. It was quite a history-filled day for all three of us. |

References

Bonk, David, Trenton and Princeton 1776-77 2009, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-844603-350-6

Breen,T.H., American Insurgents / American Patriots, 2010, Hill & Wang, ISBN 978-0-8090-7588-1

Hibbert, Chistopher, Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution Through British Eyes, 1990, .W. Norton ISBN 0-393-02895-X

McCullough, David, 1776, 2005, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-7432-2671-2

Stephenson, Michael, Patriot Battles: How the War of Independence Was Fought, 2007, Harper Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-073261-5

Online

Creesy, Virginia Kays, "The Battle of Princeton", 2016 Princeton Alumni Weekly repost from Dec. 1976, https://paw.princeton.edu/article/battle-princeton an excellent narrative of the battle and events around it originally written for the bicentennial.

Mark, Harrison, "Battle of Princeton", 2024. World History Encylopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2367/battle-of-princeton/

Cadwalader, John, Plan of Princeton, Dec 31, 1776, Mount Vernon, Library of Congress,