17 January 1746

Jacobite Rebellion

British Government Army: under Lt. Gen. Henry Hawley, Governor of Scotland, approx. 8,000 with 10 guns

Jacobite Army: under Charles Edward Stuart, approx. 7,500

Location: 55° 59' 17"N, 3° 49' 10"W, Just to the southwest of the town of Falkirk, Scotland

Weather: Cold as a witch's you-know-what; cloudy in the morning, and then, by afternoon, a sleet storm blowing hard from the southwest, into the faces of the Government forces and reportedly damping their gunpowder. Visibility: Rain turning to sleet beginning around noon, which would have further reduced visibility. Ground: Soggy

Sunrise: 08:35 Sunset: 16:18

Calculated using the NOAA improved Sunrise/Sunset calculator

All times UTC (Alpha, Zulu, which would also be local for Falkirk)

Another Victory that Lost the War.

This was the penultimate battle of the ill-starred Fifth Jacobite Rebellion, popularly known as "The '45". Those fans of the bodice-ripper Outlander TV series may not consider it an Obscure Battle, nor would many of my Scottish readers, but as this is my house and my rules, I decide what qualifies for my posts. Also, as it was fought just prior to the disastrous Battle of Culloden (well...disastrous for Bonnie Prince Charlie and his Scottish supporters, at any rate), it does have some interesting details that might shine light on that final fiasco.

(Note that this battle is not to be confused with the other Battle of Falkirk 448 years earlier; the one Mel Gibson lost in Braveheart.)

I was following my cousin's recent hike across Scotland, which she shared everyday with us on Facebook. She visited two battlefields, Falkirk and Culloden. And it sparked an old memory. When I was 17 and living with my parents in West London (Ealing, to be precise), my dad and I would frequent our neighborhood pub, the Duke of Kent, where we were embraced as amusing Yanks by the regulars. The pub was popular with several Scottish patrons and we used to tease each other about our accents, but bonding over the acknowledgement that it was the English who had the peculiar accents. One evening one of them started ranting about the "bloody Sassenachs" (i.e. "English", from the Gaelic for "Saxon"), and how much he hated them. He told us that these bloodthirsty monsters had rounded up all the people in a village near his in the Highlands, locked them in the church and set fire to it, burning them all alive; "Alive! Men, lasses, and wee bairns! Don't tell me about the &*#$@ English!" I was appalled. It was outrageous! How come this atrocity wasn't in the news? His friend, laughing, leaned into us and told us, "He's talking about the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745." I guess feelings were still trigger-happy about this period, even two centuries later, particularly after too many pints. But this was the first time I had heard about the '45. Or learned the term "Sassenach". Or "bairn".

As I researched this article (see my references at the end), I noticed again all the disparate accounts. The more I read history, the more I realize it's more like cable news; it depends on the individual prejudices and political axes to grind. Some historians try to be objective, but even my favorites cannot help but reveal their biases. In the case of the Jacobite rebellion, even though it is two-and-a-half centuries over, I noticed (as I did in that pub way back in 1967) that it isn't dead. Faulkner's relevant quote, "The past is never dead, it's not even past," is more true than ever.

So while those of you steeped in Scottish history may have favorite specific accounts yourselves, and may be incensed by the account written by this Yank amateur historian, my apologies. But also understand that in terms of the Jacobite cause (or rebellion, depending on your point of view) I don't have a dog in the fight. To me, both sides seem ridiculous. I'll have to say, though, that at least the Hanoverian position was based on Parliamentary law and the Jacobite on medieval dogma about Divine Right of Kings. So you can see where I, as an American, might also be biased.

Okay, enough prologue.

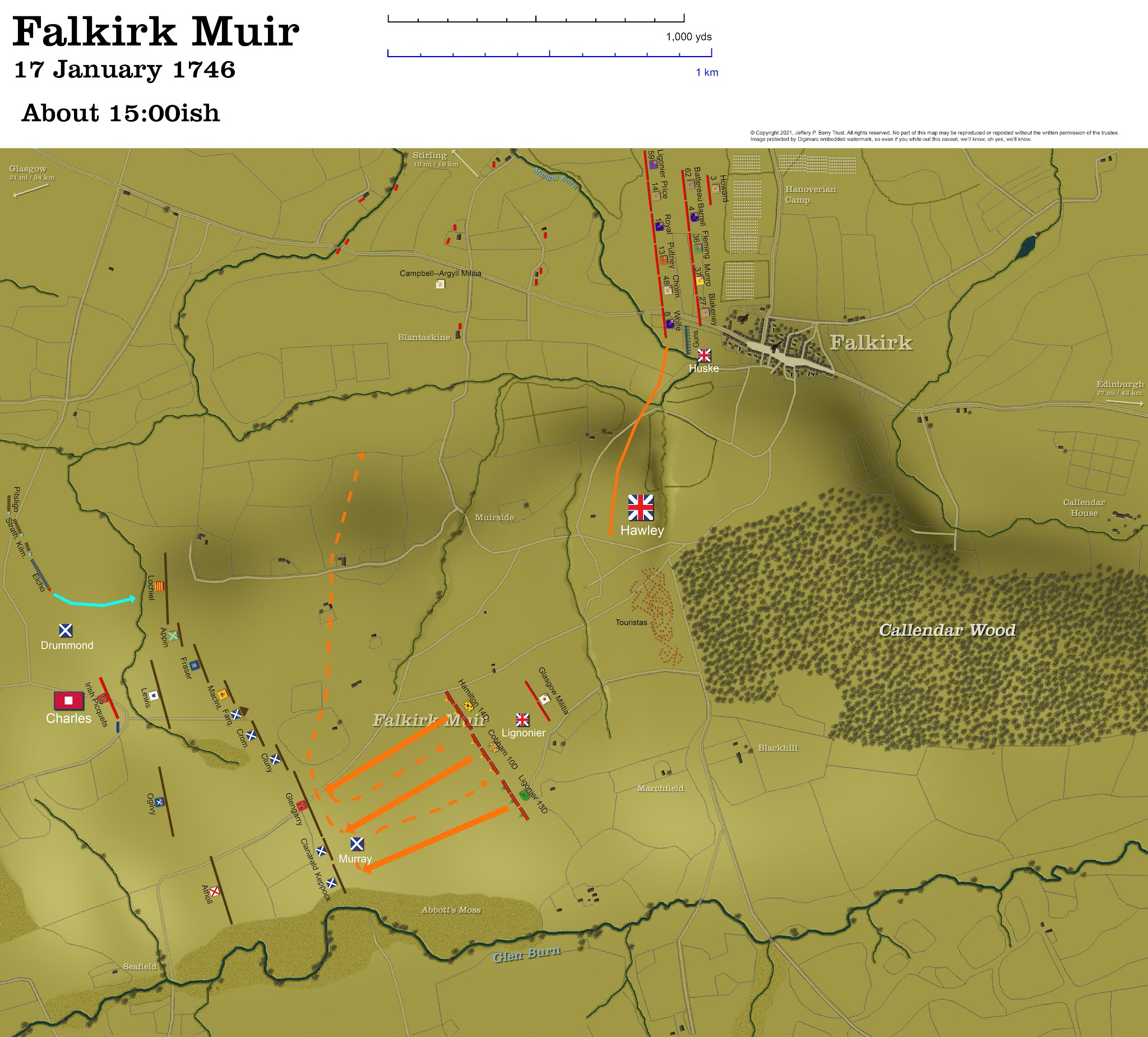

The map of the battlefield as it was starting. This was about 15:00. Very "about".

Jaco-who?

But first, before we get to the carnage (which...and let's all be frank...is why we're all here, right?), a little background. You can always scroll down. There won't be a test this time.

In 1688, following the Glorious Revolution in the U.K. which deposed the Roman Catholic, tyrannical, and much-despised Stuart King, James II (and VII of Scotland), a political movement was generated by the minority of British, who, as in so many losing political parties to this day, imagined themselves as the cheated majority. Its object was to bring back James II, and then, after he died in 1701, his son, James Francis (who, to them, would have been James III/VIII). The movement was called Jacobitism, after the Latin for James, Jacobus. And it continued episodically for almost a century.

Of course, in kicking out James, the Whig-dominated British Parliament brought over James's Protestant daughter Mary II and her husband, William

of Orange (William III), from the Netherlands to be conjugal monarchs. William was also

genetically a Stuart and Mary's cousin, so he didn't need the marriage

to be in the direct line of succession from his grandfather, Charles I, but it was a nice plus. And following the Test Acts of both the English and Scottish parliaments in the previous centuries, no monarch or any office-holder could be legitimate unless he/she was a Protestant (either Church of England, Presbyterian, or some sort of Calvinist). During two childless reigns (Mary's and Anne's) Parliament further enacted the Settlement Act in 1701 which reinforced the succession only to Protestant heirs. After Anne's death in 1714, the closest eligible heir, who was both Protestant and a Stuart, was George , Elector of Hanover, the son of James I's granddaughter (and also William III's cousin), Sophia of Hanover, who became George I, the first British king in the House of Hanover. This isn't so hard to follow, right? And it makes so much more sense than having strange women lying in ponds distributing swords as the basis for a system of government. (to quote Monty Python).

From 1688 there had been officially five attempts by Jacobites to achieve a coup to overthrow the legal monarch (well, legal if you recognize the Whiggish Parliaments that validated them) by military invasion of Britain; 1690, 1694. 1708, 1714, and 1745. All of these were backed by the French, who had a vested interest in sowing discord in their arch-enemy, Britain. The movement really never ended, but after the brutality and failure of the '45 rebellion, it withered to a pipe dream, with both the Old and New Pretenders dying of old age somewhere in their villas in Italy. The French essentially gave up backing this fruitless foreign policy after the last attempt. They had other things to worry about...oh, like the Seven Years War, or losing their colonies in the New World, or devastating famines, or, finally, the French Revolution.

But in 1745 the son of James Edward Francis Stuart (James III to his friends, or "The Old Pretender" to his enemies), Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie" to his friends, or "The Young Pretender" to his enemies) was backed by the French to launch a fifth and final invasion of Britain. Intelligence from Louis XV's agents indicated that there was widespread disaffection with the Hanoverian government in England, and particularly in Scotland, and that the Bonnie Prince and his army would be "welcomed as liberators". Ah yes. That old bit. And, of course, there was evidence of weapons of mass destruction secreted in the Highlands.

The Bonnie Prince Lands

| |

| Bonnie Prince Charlie I mean, just look at this adorable face! Don't you just want to bink that wee nose? painted by William Mosman in 1750 |

On 23 July 1745 the Old Pretender's son, the 25-year-old Charles Edward Stuart, was rowed ashore on the Outer Hebridean island of Eriksay. Originally he had had another ship with him (the Elizabeth) that had a force of French infantry and arms, but it was intercepted by the Royal Navy's HMS Lion and forced back to France after a four-day, running, sea battle. So Charles splashed onto the beach with a tiny entourage and only their own personal weapons.

Nevertheless, Charles was able to make his way over to the Scottish mainland and at Glenfinnan (see map below), formally raised his banner and declared his father the legitimate King of Scotland, England, Wales, and Ireland. A bunch of Catholic Highland clans started rallying to him, calling him the "Bonnie Prince Charlie". As in the previous four risings they were primarily Catholic, but it was also from a fever of national pride that they rallied around a "native" Stuart prince...even one born in Italy. They were still not happy with the forced Union Acts of 1706-7 which duct-taped Scotland to England by consent of both of their parliaments. After all, both kingdoms had been ruled by the same monarchs for over a century, since James I (VI). This just made it official. Not to the Jacobites, though. It may have been 57 years since James II (Charles's grandfather) had been chased out of Britain, but like that Scot I met years ago in The Duke of Kent, they weren't going to let it go.

|

| The Bonnie Prince's Glenfinnan Banner Inspiring, no? |

Meanwhile, Cope, after reinforcing Inverness in the northwest (map below), made his way back to relieve Edinburgh via Aberdeen to Dunbar at the entrance to the Firth of Forth, arriving there on 17 September with a couple of thousand troops (horse and foot), the same day the Jacobites had marched into Edinburgh. A few days later, both little armies met at the mushy field of Prestonpans, east of Edinburgh, and stared at each other for a few days. On the 21st the Jacobites executed a surprise flanking maneuver worthy of Frederick the Great and in five minutes routed the Redcoats. Just five minutes! This was, needless to say, a huge morale booster to the Jacobite recruiting campaign and an equally huge bummer to the Hanoverian loyalists. For a bunch of ragtag snerfherders to so easily beat a professional army of Regulars! Who would have thought? But, to be fair, most of Cope's army were not regulars. They were largely untrained recruits, otherwise known as a home guard. The real Regulars were still over in Flanders under the Duke of Cumberland, fighting the French.

In spite of this shot in the arm from Prestonpans, it must be mentioned that while Charles and his army were encouraged by the enthusiasm of support from Catholics and Jacobites in Scotland, they were at the same time discouraged by the sullen hostility of the majority of people, particularly in the Lowlands. They weren't welcomed as liberators as Charles had expected and been promised. His men had been forced to threaten several local magistrates and landholders, extorting material support (food, horses, weapons, lodging) on pain of death, in many cases forcing local officials to read the proclamation of James's claims in public, with guns at their heads. The economy had been doing pretty well for the past several years through increased trade with the American colonies and the West and East Indies, and this rebellion had disrupted that. Moreover, there was considerable hostility between the Highlanders, Lowlanders, and Protestant Jacobites within Charles's army itself. Old clan rivalries made Charles' task like walking on eggs. And as happens in any civil war (and the English Civil War was just a century past) there was partisan divide even among close families. So distrust was epidemic.

Map of Jacobite and Government movements in Scotland and England up to Falkirk. I have not represented the movements after that battle but have indicated the site of Culloden, the final battle of the rebellion three months later, up near Inverness.

The Bonnie Prince Invades England

Not deterred by the underwhelming response in eastern Scotland, Charles decided to take his cause south to England. Everybody knew how much the English loved the Scots. And how much they loved his grandfather James's memory (insert sarcasm emoji here). So if he were to invade that country with an army of kilted, claymore-swinging Highlanders, he concluded that the English would swarm to his banner in a flood of brotherly support. That's what he'd been told, anyway (he'd never been to England himself). He believed that his mere presence with a Scottish army in England would cause the Hanoverian government to fall, with the people carrying him on their shoulders into Whitehall. Several of his generals, including Lord George Murray, thought this was a bad idea. They were vigorous in their advice to stay up in Scotland and consolidate their position there.

So, if there are no other objections, let's go.

On 2 November, leaving Edinburgh without taking its castle, the Jacobite army, now "swollen" to almost 5,000 men, headed toward the English border at Carlisle in two columns, a strategy designed to headfake the Government commander in northeast England, George Wade, over in Newcastle. The northeast corridor into England, heading right toward York through Northumbria, was considered the logical avenue of attack, so half of Charles's force (under Lord George Murray) first marched in that direction while the other half (under Lord Perth ) went west toward Carlisle. But just before they crossed the border on the east, Murray's lefthand column jinked right and followed the border across the mountains to meet up with Charles at Carlisle (see map above).

This worked. Wade, with an estimated 11,000 Government troops, couldn't figure out where Charles was going. And this being the middle of the four century climatic period known as the Little Ice Age, the snows had already started to fall by early November, blocking the passes over the Pennine mountains between Northumbria and northwest England. So Wade marched back and forth, trying one pass after another, exhausting his troops.

The still-small Jacobite army, now reunited, marched into Carlisle. But again, as at Edinburgh, they were disappointed not to be met with throngs of supporters and volunteers, eager to see a Catholic king ruling over them again. There were some sympathizers, but most had to be pressed into service or into surrendering their horses and food under threat of "military execution", as the euphemism of the day went. The Jacobites also forced the locals to put up their men in their houses, feeding them, changing their linen, giving them their WiFi passwords. There are also many testaments by the outraged locals about how the Highlanders soiled their homes (I won't go into the gross details). If any of you Americans among my readers ever wonder about the quaint Third Amendment to our Constitution, the one about not having to quarter troops in your homes, it gets back to this common practice. In all fairness, though, It wasn't just the Jacobites who did this. All armies just moved into people's houses back then and raided their fridges.

The invasion continued on south, requisitioning, mooching, bullying, and "military executing" until it finally got to the vicinity of Derby in the East Midlands. One of its main tactics seemed to be what I call the "Airbnb Overbooking" strategy. Agents and detachments of Jacobites would fan out on either side of the prospective route of advance, making reservations at various towns for 2,000 here, 12,000 there, sparking apprehension. This accomplished two things; it spread terror in an economical way throughout western England, and it misdirected the defense by the Government. Nobody knew where Charles was heading next, and nobody knew how large the invading army actually was. When you hear of 10,000 reservations being made in one town, you tend to think that there are actually 10,000 in that party. Christopher Duffy, in his detailed study of The '45, (pp 300-313) lays out all of the possible avenues of assault on London that had been anticipated. This clever misdirection also confused the Duke of Cumberland, who had been recalled from Flanders with his troops to mount a defense of the Realm. He marched up and down and back and forth. And it set Whitehall in a panic. Now virtually all of the British troops on the Continent, as well as Hessian, Dutch, and Swiss mercenaries were called over to England.

While Cumberland had presided over the Allied defeat at Fontenoy that spring (see my post on that battle), he was still considered Britain's most talented soldier because of his brave performance at Dettingen (under his dad, George II) and, besides, his defeat at Fontenoy was actually the Dutch's fault (yeah, that was it!). His troops also seemed to love Cumberland, who, like Charles himself and other great commanders, shared their privations with them, marched on foot with them, put himself at the forefront of the fighting with them, personally rewarded them, and treated them decently, like fellow soldiers. So everybody was counting on him.

The Bonnie Prince Says "Nevermind."

For some reason, even though his progress through England had been pretty smooth, and he had reached as far as the Midlands (Market Harborough, less than 80 miles from London, where Airbnb reservations for 12,000 had been booked), and Cumberland had not yet organized his response, Charles lost his nerve.

On 5 December he held a council of war in Derby with his senior commanders (Lords George Murray, Perth, Atholl, O'Sullivan, etc.). As I said, Lord George had been against the southern invasion in the first place. The promised landing of a French army in the southeast of England hadn't happened. The response to recruitment in England had been underwhelming; in fact, there was growing resentment of the Jacobites' very presence. Everyone in Charles's staff noticed. They had only managed to raise one battalion of Jacobite sympathizers in Manchester. Both the local and national economies were collapsing in the face of the invasion (there had been a run on the banks in London and port traffic in Liverpool had stopped), which didn't bode well for The Bonnie Prince being carried on the shoulders of a grateful populace as he entered London. And it was snowing really hard. Anyway, that night, Charles had decided to retreat.

The moral effect on his army was, shall we say, not great. As Charles's regiments were ordered to get marching again early the next morning, when the sun started to come up, they noticed it was on their right instead of their left; they were marching back north! Duffy compares the psychological effect to what had happened to the French Army in the face of the German invasion in 1940, where they had been holding their own against Guderian and were suddenly ordered to fall back by the High Command. Or to the British in Malaya who had been successfully defending against the Japanese in 1942 and, without explanation, ordered to fall back to Singapore. This fateful decision also weighed heavily on Napoleon as he pondered the consequences of his retreat from Moscow in 1812. When you seem to be doing well, at least from the point of view of the frontline troops, and are suddenly ordered to retreat, it is usually taken as a sign of defeat. Lord George Murray had been right all along: This was a bad idea from the get-go.

The retreat took the army all the way back to Carlisle on the border. The whole way they were hounded by Cumberland's dragoons, who, though they were swatted away each time (as at the little "battle" of Clifton on 18 December), all this harassment eroded the confidence of the Highlanders...or, at least, insulted their honor, as if they were mere, undocumented immigrants and not liberators.

Reaching Carlisle again on the 20th, Charles made another strategically dumb decision by leaving some 394 men (whom he could ill afford from his diminutive army) and all of the guns he had captured at Prestonpans in the dilapidated fort there. They were summarily all captured ten days later. Cumberland wanted to execute all 394 as seditionists on the spot, but the Government insisted that they do it judicially, which they did a month later--either hanging them or "transporting" them to the West Indies and Georgia. "Transporting" was the euphemism for making them slaves.

Charles, after making this useless sacrifice at Carlisle, continued his retreat up to Glasgow, getting there on Christmas Day. Glasgow, which he had avoided before, was a city generally hostile to Jacobitism. Charles himself bemoaned that he seemed to have no friends there. In fact, there was even an attempt on his life by a kid firing out of a window. Charles' quartermasters had to extort over £5,000 in supplies from the local merchants. Also, before they got to Glasgow, that city, far from being a Jacobite oasis, had mustered a regiment of some 700 Loyalist militia to march off to Edinburgh to join the Government army assembling there. Charles could recruit almost nobody to his cause in Glasgow. He had a couple of city

magistrates seized as hostages, and took them with him to insure

that Glasgow wouldn't try any funny business behind him. But the whole enterprise was starting to founder.

On New Years day Charles moved his army over to Falkirk, about 20 miles east of Glasgow, and rested his troops there for a couple of days. Then he moved 10 miles northwest to Stirling and its castle, still stoutly defended by a Government garrison, arriving in the town on 4 January. When he first passed Stirling on his way to Edinburgh back in September, he had had to bypass the castle since he didn't have the means (i.e. guns) or time to besiege it. And here it was, still untaken.

Below the defiant Stirling Castle he met John Drummond's Jacobite army who had been left in Scotland prior to the aborted English invasion. Drummond brought with him about 4,000 newly recruited men (mostly Lowlanders) and six newly imported French cannon, including two big 18 pounders, with which they intended to pound the castle into submission.

|

| Stirling Castle photo by John Stocks on Google Maps |

The men started digging trenches and the guns were emplaced. But the castle is perched on top of a high, volcanic plug overlooking a flat plain. The incompetent French engineer, Mirabelle de Gordon, who had come with the guns, set them up too close, too shallowly entrenched, and completely vulnerable to the batteries in the fort. These were quickly dismounted by the guns in the castle.

The Jacobites, after over four months of campaigning, had not managed to take a single fortified position from the Government (except Carlisle, which was surrendered without a siege and then retaken by Cumberland with a siege). All of the Scottish castles, from Inverness to Edinburgh to Stirling and all the forts up and down the Great Glen (Forts William, Augustus, George) were still held by Loyalist forces. Charles, apparently had felt he had to at least take Stirling since it dominated the head of the Forth and the gateway into the Highlands. Symbolically too, it overlooked the battlefields of Bannockburn and Stirling, where Robert the Bruce and William Wallace had defeated the hated English in the middle ages. So it was a patriotic prize, one to legitimize Charles's claim--at least to the throne of Scotland for his father. But he just couldn't take it. It must have been so vexing.

Maybe not surprisingly, the Prince got sick. He had been marching on his own feet for five months in the middle of this Little Ice Age winter. He was not a weakling (don't let that portrait by Mosman above fool you). But he was not a tough Highlander either. He had grown up in a villa in balmy Italy. So, with all of his frustrations and disappointments over the past six months since he landed in Eriksay; and the cold, miserable weather; and his inability to win more support; or even to take one goddam, measly castle...Sheeze!... he was entitled to some PTO, ("personal time off" to you non-corporate types).

Also, he got distracted by another castle to storm. While resting with his cold at Bannockburn House just south of Stirling, the Bonnie One happened to meet a very charming young lady, one Clementina Walkinshaw (I love that name. She had to be a Gryffindor.) who was to become his lifelong soulmate...at least until he became a burned-out, middle-aged, abusive alcoholic back in Italy and she had to be rescued by Charles's dad. But for now, love was in bloom.

So that takes us up to the main point of this article, the Battle of Falkirk Muir. Which I'll begin now.

Hawley Moves His Army to Falkirk

Lieutenant General Henry Hawley had been recently appointed as military governor of Scotland after Cope's loss at Prestonpans. He had distinguished himself in Flanders under Cumberland as a brave and competent cavalry commander, so the Duke had confidence in him. But he was also infamous among his own troops and the Scots as "Hangman Hawley" because of his ruthlessness, his sadism, and his readiness to summarily execute not just enemy prisoners but even his own men. His own commander, the Duke of Cumberland, apparently despised him and on several occasions actually countermanded his executions and whippings, admonishing him for going too far. (And we know how fondly Cumberland was thought of in Scotland.) One anecdote mentions Hawley as having the corpse of one of his victims hanging in his tent. Ah! What's that smell?

|

| Lt. Gen. Henry "Hangman" Hawley by Christian Zincke 1746 |

Falkirk was crowded with thousands of sightseers who had come in from all over to witness the anticipated battle. It was like an 18th century Burning Man festival. Prices of lodging, food, commemorative T-shirts, glo-sticks had gone through the roof. (okay, maybe no T-shirts or glo-sticks). This reminded me of all the sightseers who had traveled out from Washington to witness the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, the opening battle of the American Civil War which Washingtonians thought would be a walkover for the Union. People are idiots. It's comforting to realize not just in our time.

This influx of tourists didn't particularly hinder Hawley's army. The regiments just set up their tents to the northwest of the town behind a defensive gully (The Mungal Burn) and by 13:00 they were cooking their dinner (or tea or whatever it is the Brits eat in the middle of the afternoon). Hawley and his officers just threw all the tourists out of the spacious Callendar House on the east side of town and moved in there. The Argyll and Glasgow militias, who didn't have tents, moved into all the houses and barns to the west of the town, ostensibly to guard against a Jacobite surprise attack.

| ||

| Contemporary view of Falkirk from the south, with its iconic Trinity Church and clocktower Steeple. | |

Hawley and his staff got up at 05:00 the morning of the 17th and after First Breakfast went out to use their spyglasses to see if they could see any evidence of aggressive Jacobite movement coming from the direction of Stirling. A large wood, called the Torwood, blocked their direct view of Stirling, but they could see no activity coming out of it. The Jacobites were coming, but nobody saw them yet. Evidently they had left enough people back at their camp to keep the campfires burning to fool the enemy.

A local Loyalist, one Alexander Grosset, though, took his servants and his own spyglass further west to see if he could see anything coming from that direction. By mid-morning he did detect a large mass of horse and foot marching from behind the Torwood, seeming to head toward the southwest, possibly in the direction of Glasgow. He sent an urgent message back to Hawley that the enemy was on the move, but he couldn't yet see in which direction. Hawley, who had gone back to Callendar House to enjoy his Second Breakfast, and satisfied that the enemy would not attack that day, refused to get up from his scones and merely ordered that the men put their kit on, but that they didn't need to fall in. Yet.

Earlier that morning, Charles's own scouts had reported that the Government army had moved into Falkirk the day before, but that--at least as of that morning--there didn't seem to be any further movement by them; the Redcoats' hundreds of white tents were still up and they hadn't mustered. Charles and his staff thought they saw the chance to catch Hawley like they'd caught Cope at Prestonpans. The Prince ordered everybody to break off work on the siege for the day, form up in battle order, and start to march toward the enemy. By plan, though, they formed into columns of route (three men abreast) and took a more southerly route so as to come at the Government position from the southwest, concealed by the mound of the Falkirk Muir. By way of misdirection, Charles had Lord John Drummond take his cavalry, plus Ogilvy's and Lewis's Lowland infantry, and approach Falkirk from the northwest, crossing the Carron creek at the village oft Larbert, northwest of Falkirk. And making a big noise while they did it

This indirect approach was almost exactly the tactic that Frederick the Great had used at Leuthen eleven years later (see my post on that battle), and what the Zulu had used at Isandlwana over a century after that: Fix the enemy's attention with a smaller force in front of them, while sweeping around their flank, using the land to conceal your main assault.

About noon Hawley's dragoon pickets had started galloping in to report that Jacobite cavalry was coming at them through Larbert. But the volunteer, Mr. Grosset, who had not stopped watching from his post farther west, sent another message that the main Jacobite army had changed direction and was now starting to ford the Carron farther upstream, at a place called Dunipace, heading toward the southeast. Hawley's second-in-command, Major General Huske, who had not gone back to Callendar House for scones, finally ordered that his infantry fall in and form up, which they did within half-an-hour, their double lines facing due west in front of the tents, the Munghal Burn, a natural moat, in front of them. Huske was confident of the strength of the defensive position. He also ordered Capt. Cunningham to set up his ten guns on the left flank of the line, covering the approach.

But now John Drummond's diversion pulled back from the bridge at Larbert and his column moved west to start to cross the Carron at Dunipace, behind the main Jacobite army. Huske realized, from Grosset's and his dragoons' further reports, that the main rebel army was now coming up on the far side of the Falkirk Muir to outflank them, just like they had done at Prestonpans. In reaction he ordered his infantry to left-face and quick march by files across the main Glasgow road, up onto the muir, and reform facing southwest, below the town. Local farmers and their families, realizing what was happening, started fleeing their farms to the south and west of the town and flooding into Falkirk.

General Huske's dozen Government foot regiments were moving as fast as they could, but were struggling with muddy ground in trying to climb up onto the plateau from the north, somewhat slowing their progress. And the guns following them became hopelessly stuck. They had to have been re-limbered from their original deployment across the Glasgow road by civilian contractors using plow horses, unused to hauling artillery. This was long before Frederick the Great's innovation of militarizing his own artillery. These guns hadn't got but a hundred or so yards up a ravine on the northeast side of the muir before the lead pieces (two 6 pounders) sank up to their hubs in mud. Capt. Cunningham, who had been given responsibility for the artillery without adequate manpower (just 10 sailors and some local teamsters), not enough horses, and completely inappropriate equipment to pull them, finally gave up, cursing.

By this time Hawley had joined Huske and had ridden forward up onto the muir to see, for the first time, that the main Jacobite army was coming up from the southwest to the crest of the ridge. This was going to be Prestonpans all over again! (What Huske undoubtedly had just said.) Hawley approved the move.

Prestonpans All Over Again

Repeating Prestonpans was exactly, in fact, what Lord George and Charles had in mind. They were going to position the army to the southwest of Falkirk on top of the muir and at dawn launch a flank attack. By the time they had got to the top of the hill (beating the Redcoats to it), it was about 15:00, with only a little over an hour of daylight left (official sunset at 16:18). And, as if that weren't enough, it had started to blow very hard. A freezing rain had picked up, driving right into the faces of the Government army. So it was also getting prematurely dark. All of the spectators who had been set up to picnic south of the town, were now starting to pack up and head back to shelter of the town.

Hawley, not wanting to get caught in this trap, and seeing the trouble his infantry were having climbing up the hill, ordered his three dragoon regiments to hurry forward to attack the Jacobite right flank before they could dress their lines, and to give his foot time to deploy.

|

| Falkirk Muir today. Looking east from where the Jacobites began to move toward Falkirk. There were, apparently, no woods on it back in 1746. Photo by Susan Brigham. |

By about 15:00-ish (none of the sources I relied on were specific about the timing of this battle), the Jacobite army under Lord George Murray had started to form up perpendicularly across the spine of the muir. He anchored his right on Abbot's Moss, the swampy ground bordering the Glen Burn (see first map above), with his right-hand company of Keppoch's MacDonnells actually sloshing around in the bog. This would protect his line from being outflanked by the Redcoat dragoons he could already see assembling about 600 yards to the east. The subsequent Highland regiments (right to left; Glengarry, Clanarald, Cluny, Cromartie, Farquharson, MacIntosh, Fraser, Appin, and Lochiel's Camerons). about 5,300 in all, began to fall in as they marched up the left bank of the Glen, past Seafield Farm. All formed up in three ranks, except Farquharson's small battalion of 150, which fell into a wedge-shaped formation, with the clan chief at the apex.

Behind this first line, from right to left, Atholl Brigade lined up with Ogilvy's, and Lewis's Lowlander regiments, about 2,400 men. Then came the three hundred or so horse under Elcho, Kilmarnock (owner, ironically, of Callendar House, where Hawley had spent the night), Stathalian, and Pitsligo. Charles himself took up position on a hillock on top of the muir a few hundred yards to the west, guarded by the three hundred or so Irish Picquets and the two companies of Royal Ecossais that Louis XV had generously lent him. The Jacobite guns themselves had also gotten stuck in the mud and left far behind on the other side of the Carron. The weather and the ground this day did not lend itself to deft maneuver.

| |

| Lord George Murray Probably Charles's most able general. |

Francis Ligonier, leading the Hanoverian cavalry, had his troopers make a series of feints in an effort to get the rebels to fire at them at long range. His experience had been that the Highlanders tended to get hyper-excited and that it was easy to provoke them into premature fire. Since they did not tend to have manufactured cartridges but were forced to laboriously load their muskets the old fashioned way, (pouring gunpowder out of a horn, dropping in the bullet, etc.), in practice, after they had fired off their first round, it would take them several minutes to reload. Instead they tended to throw down their guns once they had fired and pull out their claymores. But Lord George was mindful of this indiscipline too and stood in front of Keppoch's regiment and roared at the men to hold their fire until the enemy was within pointblank range. The signal would be that he himself would fire his own musket. And they obeyed him, holding their fire until...

As I said, it had started to rain,and the wind picked up from the west, right into the faces of the dragoons. Some accounts say the rain quickly turned to horizontal sleet, which was really stinging the Hanoverian dragoons. Now Ligonier ordered a general charge, still hoping that the Highlanders would fire prematurely and ineffectively. But the ground on the muir was pretty gooey and full of holes dug by the locals to extract peat. So the progress of the dragoons never got much above a slow trot. And their tight formation started to come apart.

The 800 dragoons got to within ten paces of the Jacobite line when Murray fired his own firelock. That was the signal. The whole line to the left of him went off like a chain of firecrackers rolling north. The volley took down about eighty horses and men. But the dragoons kept on, crashing into the ranks of the Jacobites, hacking down on their heads with their swords and firing their pistols. Instead of running, though, the Highlanders dropped down and stabbed at the horses' bellies with their dirks or pulled the troopers from their horses. All Highland ranks dropped their muskets, whipped out their claymores and charged forward. It became a donnybrook (I know that's an Irish, not a Scottish term, but you know what I mean; a knock-down-drag-out-fight).

|

| Battle of Falkirk by Lionel Edwards |

Unfortunately for the Government side, two of the mounted regiments, the previously disgraced 13th and 14th Dragoons who had fled at Prestonpans at the beginning of the war, again covered themselves with glory and ran away this time too, stampeding back into the supporting Glasgow militia. The Glaswegians, seeing the routed Redcoats bearing down on them, lit off a volley themselves to stop them. It didn't. The horsemen, and many riderless horses, just plowed into the ranks of the friendly militia and trampled or took many of them with them back into the Callendar Wood, and on to Edinburgh.

One excuse of why these two regiments bolted was that their horses, replaced since they had lost theirs at Prestonpans, were green and unused to gunfire. One account claims that some of them stampeded or threw their own riders when the dragoons fired their pistols over their heads. Yeah. blame it on the poor horse.

Cobham's 10th Dragoons, however, apparently still had their combat-seasoned mounts from their Flanders campaigns. Instead of fleeing back to Edinburgh with the rest, these dragoons wheeled right and rode north across the face of the forming Jacobite line, taking flanking fire the whole way, until they pulled up on the right of the forming Government foot and Ligonier managed to rally them.

So point one for the Jacobite team. But Lord George Murray lost control of his right-hand regiments (all the McDonald's, McDonnells, and the Atholl Brigade, about 2,500), who continued to chase the fleeing dragoons and Glasgow militia--and, presumably, the civilian spectators--off the muir and into the Callendar Woods. Ironically, due to their impetuousness and indiscipline, half of Lord George's victorious troops also became MIA for the rest of the battle. So point for Team Hanover.

Below, aerial view of the battlefield looking south. You can clearly see in this photo the topography of the ground. The location of the Monument (lower right) is the end of the gully (or "ravine") in which the Government guns got stuck. The Jacobite line would have been arrayed across the width of the ridge in the middle distance, facing the Government line roughly parallel to the tree-lined road running down to the Glen Burn at the bottom the hill in the distance. None of the contemporary maps of the battle indicate trees on the actual field, though they do elsewhere (e.g. the Torwood to the north), so I have to assume that no trees were on the moor in 1746. A complete 360 view of this shot can be seen on Google Maps. Photo credit: D. Wilkinson.

One of "Charlie's Stones" marking the assumed position that Prince Charles was said to have taken, about a mile southwest of the front line. In the aerial pano above, there would have been no trees obstructing his view then. The "CR" engraved on one of the stones (for "Charles Rex") was thought to have been carved as a graffitum in the early 19th century. He wouldn't have been eligible for the Rex part in 1746. Apparently, some partisan vandal changed the "C" to a "G" for George (clever, clever) sometime later.

Photo by Susan Brigham.

Act II: The Redcoats Are Coming!

It had only taken the Government foot about half-an-hour to march up onto the muir and face the Jacobite line (see my comment on "Timing" in my Armchair General section below). By this time, though, their artillery were hopelessly stuck in the mud on the slope behind them. Nevertheless, as they crested the hill, they formed up in two lines--well, roughly. Apparently in the muck and the rain, the 18th century geometric perfection of the two lines was off. So they were still shuffling into place when the storm hit them.

Though the left of the Jacobite first line (right to left, Cluny, Cromartie, Farquhason, MacIntosh, Fraser, Appin,and Lochiel's Camerons) was also still getting into position, they had become very excited as the Cobham Dragoons galloped across their front. They fired at dragoons, also hitting some Government foot behind the them. Then, seeing the other Hanoverian horse and Glasgow militia fleeing before the charging MacDonald's to their right, they decided to join in the fun. Highlanders dropped their empty muskets, whipped out their broadswords, and charged helter-skelter at the enemy in front of them.

By this time the sleet was making the assembling Government foot squint and bow their heads. As they were right-facing and dressing their lines, they couldn't help but notice all the dragoons, the Glasgow militia, and the thousand or so spectators fleeing, many of them right through their own lines. Apparently the left-hand regiments (Wolfe's and Cholmondeley's) actually fired at the retreating horsemen to ward them off. But these broke up the infantry formations in their panic and it spread like wildfire.

Through the sleet these troops saw and heard the horde of screaming, sword-swinging Highlanders running at them. Though they had a ravine between themselves and the enemy, the Jacobites, seemed to have no trouble swarming down and up the other side. The government regiments let loose platoon volleys into their faces, but it didn't seem to stop the tidal wave. One explanation was that in the rain, they noticed that some of their muskets misfired; the gunpowder soaked in the pans (I have a further comment under Armchair General on the supposed wet powder later, too,) Normally this kind of controlled, platoon fire, which the British infantry were famous for, would have done the trick in stopping the Highland charge (as it would later at Culloden). But the more likely explanation why it didn't this time was that Government infantry overshot the Highlanders climbing up the near bank of the gully. But whether it was with the soaking powder, the steep slope, the freezing storm in their faces, or just the mob of homicidal maniacs about to crash on them, something snapped.

The Government infantry started to break. First the rear ranks in ones and twos, like a few pebbles starting an avalanche. Then one regiment after another, from left to right, came completely apart. The officers themselves did not break, but tried valiantly to steady the men and rally them. Hawley rode up and down pleading and threatening to shoot down anyone who tried to flee (his usual leadership style). But soon he himself was swept away by the tide of panic (or so he claimed). The victorious Jacobites kept after them, hacking down any slowpokes, and even slaughtering the panicky civilian tourists who got caught trying to make their way back into downtown Falkirk from the muir. These were all closely chased by the whole Jacobite line, who, as the MacDonalds did on the right, completely lost their order in the heat of the charge.

An 18th century British battalion, executing its well-drilled platoon volleys, which resulted in more or less continuous fire. The battalion was divided into 18 "firings" or platoons. The first "firings" would all fire in a rapid sequence, and then immediately begin to reload (the average reload time with cartridges was about 20 seconds). Then the second "firings" would follow, and then the "third", all carefully staggered so the there was a continuous hail of lead all across the battalion. When done right, this drill would make the battalion essentially unapproachable from the front. In some cases, as at Falkirk, the front rank would kneel with their bayoneted muskets pointing forward like a fence, holding their fire in reserve in case the attacker managed to make it through the fire of the two rear ranks, then all firing into the chests of the enemy.

But on the Government right, Major General Cholmondeley, whose own regiment had bolted, rallied three-and-a-half regiments (Ligonier's 59th Foot, Barrell's 4th, Howard's 3rd, and a portion of Price's 14th), wheeled them left and had them fire volley after volley into the left flank of the charging Highlanders. The Hanoverian quartermaster later tallied up that they had fired off 15 of their 24 rounds. These four regiments not only kept their cool, but also, evidently, kept their powder dry. At least dry enough to unleash hell on the Jacobite flank. Also about this time, the rallied 10th Cobham Dragoons under Ligonier showed up again and charged into the flank and rear of Lochiel's Camerons on the Jacobite left.

This did the trick.

The Highland charge stopped. Their own surprise at being outflanked and ravaged on their left caused them to panic in turn. And they began to run back the way they had come, like a wave that receded from a breakwater. Charles had sent his bodyguard, the Irish Picquets and his two companies of Royal Ecossais, up to support the charge, and while they did not break themselves, they were not able to stop the general retreat.

Aside from the ongoing slaughter of the fleeing Government soldiers and local civilians (some of whom were even Jacobite sympathizers), this last heroic act on the part of those four regiments that Cholmondeley had taken charge of ended the battle. And, in so doing, they saved the retreating Government army. There was mayhem everywhere, on both sides. Except in those regiments who managed to march away intact.

This was another example of that same act by the rearguard of the retreating Union army at Chickamauga I had described in my earlier post on Snodgrass Hill 1863. Poetically, many of the Confederates who were charging at that later Civil War battle were the descendants of the same Jacobites who had done the same thing during "The '45", after their great-great-grandfathers had been deported to the Georgia Colony in 1746.

Eyewitnesses say that the whole battle had lasted less than half-an-hour. Some say ten minutes. Timing is vague.

So who won? I mean really?

Of course, by this time, about 16:30ish, the sun had set (as it does this time of year that close to the Arctic Circle) and the darkness and sleet prevented anybody from seeing what was going on.

Though histories give the technical victory to the Jacobites, at the time neither side knew who had won. Some, like the MacDonalds and MacDonnells on the right assumed they were victorious since they had caused the general rout of the dragoons to their immediate front and had run on after them, not seeing what was happening on their left over the crest of the hill, and in the rain, and the failing light.

On the other side of the battlefield, the four Government regiments under Cholmondeley thought they had won the battle when they managed to stop and drive off the Highland charge with disciplined platoon fire and a last cavalry charge by the 10th Dragoons.

Prince Charles, who was about a mile back from the battle, couldn't tell what was happening and had to rely on conflicting reports. It wasn't until after midnight, when reports came in that the Government army had withdrawn from Falkirk that he decided to move into town.

Hawley, who had allowed himself to be swept along by the retreat of the infantry (funny that his subordinate officers didn't allow themselves to be swept in the same way), was on his way back to Callendar House to pack up his things. He assumed he had lost. But then, in his report to Cumberland, he described it as "a severe check to the Highlanders'" offensive on Edinburgh, and the only reason he had fallen back to Linlithgow was because it was raining really hard in Falkirk, otherwise "we were masters of the field", and that he would return the next day to reclaim the town and move on to relieve Stirling. I'm sure everybody back at Cumberland's headquarters bought this.

In actuality it seems that the only formed troops left on the battlefield were those four Government regiments under Cholmondeley, the 10th Dragoons, and the Argyll Militia. On the Jacobite side there were only the 300 (more or less) Irish Picquets and Royal Ecossais and the small cavalry regiments. Bailey says that Lord George had also managed to rally about 800 of his original 5,300. Otherwise, both sides were pretty much dispersed.

Hundreds were killed or wounded. But as the Highlanders and locals went right in that night like jackals to strip the dead of their valuable shoes, pants, coats, kilts, cloaks, socks, and all, no one could tell how many Jacobites or Hanoverians lay on the field. One described the ground as if covered in sheep. All naked corpses look alike. Even though though the bodies (and the wounded) had been stripped, local people said they could tell the Hanoverian dead because of the deep broadsword wounds in their shoulders and heads. But these might also have been innocent civilian spectators, caught by the Jacobites in full, homicidal Purge rage.

So the comparative toll was not known. Duffy says that reports of the Jacobite dead varied from as few as 50 to as many as 1,200, both numbers which he doubts. On the Government side Hawley's quartermaster reported 67 killed and 280 missing (i.e. had been captured, deserted, or left wounded on the field). But Duffy thinks these numbers were downplayed for political reasons. Charles's quartermaster Col. MacLachlan claims he counted more than 800 English dead on the battlefield the next day. Also doubtful, especially as pointed out that it was hard to distinguish Jacobite from Government from civilian naked corpses. The best estimates were that about 3-4% of both armies were casualties, which is not what you'd expect from a decisive victory.

But, technically, was it a Jacobite victory as conventional narratives credit it? By 18th century custom, whoever remained on the battlefield got to claim victory. But so many of the Jacobites had fled the field westward, thinking they had been defeated, or eastward, chasing the fleeing Redcoats, that for a time it looked as though nobody but the Hanoverians were left on the field. The intact regiments under Cholmondeley (59th, 4th, 3rd,14th Foot and the 10th Dragoons) marched in order back into camp and started cooking dinner. The cadres of several other regiments began to return to camp, too, rejoining their regiments whose officers had not fled. It was not until after midnight that the order was sent by Hawley (back in Lithlingow) for the army to pack up and join him there.

|

| Linlithgow. where Hawley's army rallied. Image from Robert Craig's blog LoveofScotland |

Nor had the Jacobites even captured the ten Government guns that had been stuck in the mud. Nearly all of Capt. Cunningham's ad hoc crew of civilian teamsters had joined the fleeing soldiers as they passed by, but with his handful of remaining sailors and the help of some of those retreating infantrymen, he had three guns hauled out and conveyed back to Linlithgow. The other seven guns he had the presence of mind to have all spiked (nails driven into their touchholes, making them useless). Hawley, who had not given Cunningham the means to move his guns to begin with, nevertheless, still wanted him hanged. (I guess the corpse "example" hanging in his tent needed refreshing). Cunningham was arrested but while awaiting court martial, he sadly slit his own wrists. In my opinion it was Hawley who should have slit his.

Something like five hundred muskets and about 4,000 lbs of gunpowder from the abandoned camp had been captured by the Jacobites. Usually a victory also meant a harvest of enemy flags and symbols, but Charles's men had only managed to collect three dragoon guidons and a kettle drum (Oh boy! The kids are gonna love this!). None of the infantry flags had been captured from the retreating regiments. Ironically, one of the Jacobite regiments (Ogilvy's) had lost its flag when its young ensign dropped it in the mud to flee himself.

The winter storm raged on all the next day. By that time all of the bodies had been stripped by the locals, and the wounded not moved or stabbed had died miserably in the freezing wet mud from loss of blood and from exposure

Atrocities and Propaganda

There were also reports of widespread atrocities committed by the Jacobites; that Highlanders wandering the field collecting dead would summarily kill any wounded person they came across, English or Scot. This story later led to Hawley ordering the murder of Jacobite wounded after Culloden, in retribution. (Though, let's be frank, given his homicidal tendencies, he probably would have done it anyway.) Another story described the Highlanders even burying one of their own wounded still alive, telling him to quit his sniveling as they shoveled mud on top of his face.

The locals of Falkirk also reported that the victorious Jacobites had acted pretty much like cossacks on the days after the battle, looting the houses and farms, even of locals who protested that they were loyal to James Stuart. "Yeah, that's what they all say," they were told. And it was also reported that as prisoners were brought in, many were brutally stabbed to death by the Highlanders who received them.

Of course, much of this, if not all, should be judged extremely skeptically, as nothing more than sneering Hanoverian calumny, sown for propaganda. But these stories, which spread rapidly, true or false, served to enrage Cumberland and his Government troops, and indeed all of Hanoverian Scotland and England. They fed the atrocities of the "pacification" of Scotland after Culloden by Cumberland, who, though by nature an enlightened and forgiving soul, was himself persuaded that he had been fighting consummate evil.

Defeat Snatched From the Jaws of Victory

The army also started to fray internally as ancient clan rivalries re-emerged. Two days after the battle, there had been an unfortunate, freak accident in which a soldier of the Clanarald regiment had been cleaning a captured Brown Bess musket when it went off accidentally, hitting the young colonel of the Glengarry regiment, Aeneas MacDonnell, who happened to be standing in the street outside the window. There had long been bad blood between these two subclans, the Clanarald MacDonalds and the Glengarry MacDonnells, even though they were relatives, and Glengarrys were sure that "this was no accident!." They wanted the Clanarald "assassin" executed. Though colonel MacDonnell didn't die for another three days, he insisted that the he was sure it was an accident and forgave the man. But when he eventually slipped away, the Glengarrys demanded that the Clanarald soldier be executed or they'd leave the cause. Reluctantly, the chief of the Clanaralds agreed to sacrifice his hapless soldier and they shot him with a firing squad, his own dad being one of the executioners (so that his son would die painlessly). But this incident re-opened an ancient feud between the two largest Jacobite regiments that was to weaken the cause clear up to Culloden.

And Charles didn't help. Everyone noticed that Charles didn't show up at Aeneas's funeral. The excuse that he was sick didn't fly. A true Highlander wouldn't moan in bed pathetically with a head cold when one of his loyal braves had died fighting for him.

|

| Clementina Walkinshaw The Bonnie Prince's girlfriend,with a name right out of a Harry Potter book |

I don't know what The Young Prince had to do with these internal negotiations about the death of Aeneas MacDonnell, but he must have certainly been aware that his army was coming apart at the seams. Strategically he seemed unsure what to do next: Chase Hawley to Edinburgh or go back to Stirling and try to complete the siege? Eventually he decided on the latter. His best commander, Lord George Murray, was all for following up the victory and destroying the Government army at Edinburgh before it could recover. That Charles rejected this option further exacerbated a rift that had been developing between them since the ill-thought-out invasion of England. And when Charles decided he missed his new mistress, Ms. Walkinshaw, and retreated back to Bannockburn House to snuggle with her with his sniffles, Murray was completely disgusted.

Apparently Charles was sure that when the stubborn garrison of Stirling Castle had heard of his "overwhelming victory" at Falkirk, they would immediately surrender. But since the paucity of artillery and the incompetent French engineer, Mirabelle, had made virtually no dent in the high fortress, and loyalist prisoners continued to escape their lax Jacobite captors and make their way into the castle to tell their own tale of Falkirk, the castle commander, Sir William Blakeney, issued a very rude reply to the demand to yield--rather like General McAuliffe at the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. I imagine the F-bomb was dropped--in that polite, 18th century way. ("I pray yr Highness might enjoy ye delight of carnal relations with yr honorable self," or something.)

Moreover, the Royal Navy had tightened its blockade on the upper River Forth, cutting off all communication with support from France. So Charles decided to abandon the siege and move on up to Inverness to regroup. Hopefully all the Highlanders who had gone back home for Winter Break would return there. This, as events would unfold, would spell the final doom for the last Jacobite attempt in Britain. By 20 September, five months after Culloden, Charles Edward got on a ship and returned to France, telling everyone to hang tight, he would be back with a new French army and more weapons.

He never did.

And Jacobitism withered. But at least not in the Duke of Kent pub, where, 221 years later, my dad and I were listening to a Scot rail on about the bloody Sassenachs.

Armchair General Section

Bad Leadership

Looking at Falkirk closely one glaring thing stands out for me: incompetent leadership at the top. There was inspired and professional management on the subordinate level, with generals like Lords George Murray, Elcho or Drummond on the Jacobite side, or Huske, Chomondeley, Ligonier on the Government side. But the two commanders-in-chief at Falkirk, Prince Charles and Hawley, were absent, both physically and mentally.

Charles never got closer than a mile to the front. Most of the action happened over the crest of the hill where he couldn't see it. He relied on staff officers like O'Sullivan to report back to him what was going on. Likewise he couldn't be seen by his own troops to inspire them either. While Murray was trying to directly control and then reform the right wing, leading from the front, he couldn't see what was happening on the left of the line, and Charles hadn't bothered to assign a commander for that part of the army; each regiment or clan moved on its own hook. So when the men there saw the dragoons and tourists starting to run, they all decided to charge too. And there was nobody to restrain them or hold regiments in reserve. Both the front and second lines all charged at once. Virtually the whole Jacobite army was disordered with the only reserves being the 300 or so men of the Irish Picquets, the Royal Ecossais, and the small cavalry regiments under Elcho, Pitsligo, Strathalian, and Kilmarnock.

The Prince also did nothing after Falkirk. It took him and his staff awhile to realize that the Hanoverians had abandoned the town in the early morning hours of 18 January. But when the Jacobites finally marched in, there were only about 1,200 of them left under arms to do it. The rest had retreated back toward Stirling and beyond, many heading home to the western Highlands to stow their loot.

The Bonnie One also did nothing to address the deteriorating friction among the clans (especially after the accident that killed young McDonnell) but let the bickering fester and ultimately degenerate into open hostility. He let his relationship with his most competent generals (like Murray) decompose, assuming an authoritarian, because-I-said-so attitude with them.

Charles also squandered the narrow victory he assumed he had achieved by allowing the Government forces to get away intact, and giving them time to reform, re-arm, and retrain. The lax security enforced by the Jacobites let so many of the captured Government prisoners escape and find their way back to their regiments in Edinburgh, so Charles had done almost nothing to harm, much less destroy, the Havoverian force.

And he absented himself for days at Bannockburn nursing his cold, letting Clementina soothe his fevered brow.

It was like Prince Charles had lost interest in the whole enterprise once he retreated from England. He didn't want to pursue Hawley into Edinburgh before the Hanoverian forces could regroup. He lost interest in taking Stirling Castle. And, later, in March, he lost interest in trying to destroy Cumberland's army the night before Culloden when he called back the surprise night attack when it was almost there. And finally, at Culloden itself, as at Falkirk, he stayed way behind his men who were dying for him at that last battle.

On Hawley's part, he himself couldn't seem to be bothered during most of the day at Falkirk. He assumed, in spite of a very active reconnaissance to the contrary, that the Jacobites weren't going to attack him. After returning from his predawn ride to the camp, he refused to leave the comfort of the Callendar House to call his army to arms, letting his subordinates do it. And when the Jacobites were definitely seen crossing the Carron toward the middle of the afternoon, he belated rode over to see for himself, approving the defensive measures that his subordinate, Huske, had the initiative to take himself.

About 14:00 or so, when he rode up to the camp and it had become clear that the enemy were on the way to outflanking him, he reactively ordered the three dragoon regiments to hurry over and stop them, not bothering to see whether the ground on the muir was suitable for cavalry (which it wasn't). He also ordered the foot regiments to march up onto the muir but left it to Huske again to supervise that.

And at the end of the battle Hawley fled with the rest of the regiments, leaving the rear guard action to Cholmondeley, Ligonier, and all of his other officers who had stayed and done their duty. Of course, in his reports to Cumberland, he made himself the hero and described the great victory he had achieved, which was why, evidently, he decided to retreat to Edinburgh. He talked tough, but he was a creampuff. (You are what you eat, they say.)

About the rain

Bailey, in his excellent and detailed history, mentions that the Government troops were dismayed to find that their firelocks were hampered by the wet weather, and that may have been the cause of their precipitate retreat. He says that they found that one fifth of their rounds failed to fire. But, to put that in context, that is not much worse than the normal 15% misfire rate that was common for flintlock muskets during the period. Moreover, he and Duffy both describe the disciplined and devastating platoon fire that Lignonier's, Barrell's, Howard's, and Price's regiments delivered on the Jacobites. Apparently their powder wasn't affected. Nor, evidently, was the powder of Murray's Highlanders when they unleashed their single, devastating volley in the face of the charging dragoons, reportedly killing 80 outright (so they claimed). So I am not convinced that rain was the mitigating factor in the retreat of the Government army--at least not so much as the absence of overall command.The rain may have had an irritating effect driving into the faces of the Government troops, but it's hard to see it as a decisive factor.

The Prestonpans 2.0 Plan

Murray's (with Charles's consent) original plan had been to position the army on the right flank of the Falkirk position and, as at Prestonpans, launch a dawn attack, surprising the Government troops resting cluelessly in camp. I guess they thought nobody would notice 7,500 men hiding in plain sight below the town. By about 15:00 preparations for this pre-positioning had not yet been completed when the Government dragoons launched their attack. It mystifies me that Murray wouldn't have expected Hawley to see them all down there and try to counter it. Dragoons and loyal volunteers like Alexander Grosset had been closely monitoring Jacobite movements most of the day.

Murray's plan seemed, to me, like the dumbest ambush ever conceived. Unless, of course, it wasn't his plan all along. Perhaps he meant to attack toward the end of the afternoon after all.Timing

There seemed to be some confusion in the narratives about when, exactly, the battle started.If the action started sometime after 15:00, that would have left only a little over an hour until sunset (16:38 according to the NOAA calculator for that date and location), with the light already fading because of the rain squall. The Jacobite line was not yet formed fully by this time. And, as I pointed out, Charles had not assigned a local commander of the left of the line when each regiment took it upon themselves to fire and charge.

It is also confusing to me why (of, indeed, if) it had taken a half-an-hour for the Government foot to get to the top of the muir if they had started a flank march at 15:00. They only had about 700 yards to cover, and even slogging slowly through wet turf it should have, at most, taken them about 10 minutes to cover that distance.

So there are some timing and sequence-of-events anomalies in the histories. Could it have been that the Government foot started later? Or that they got confused about where they were supposed to go? Or that they got up onto the muir, but took some time in aligning their ranks in the driving rain?

The Government army didn't retreat, at least at first.

According to Bailey, the still-intact regiments (Ligonier, Barrell, Howard, Price and the Cobham Dragoons) didn't retreat at once either. After they had driven off the left of the Jacobite line, they marched in order back into camp and started to cook dinner, apparently intending to stay there the night, at least, and be ready to repel another attack from that strong position in the morning. This wasn't the behavior of a defeated army. Many of the other Government regiments were rallied, at least in their cadres, and either billeted in Falkirk or found their way into the camp as the night progressed. It wasn't until well after midnight that Hawley sent an order for everybody to pack up and move back to Linlithgow, where he had bravely run away.On the Jacobite side, Charles and his staff were unsure if they had, indeed, won or lost the battle. Their scouts from Kilmarnock's and Elcho's cavalry reported cooking fires in the Government camp. It didn't look like the Hanoverians were leaving. It was only after more reports came in in the wee hours that the enemy had finally started marching (not running) eastward out of town, that Charles felt safe enough to go into Falkirk and find a cozy room to sleep in. By this time the Jacobites had managed to re-organize a fraction of their original force (about 1,200) to occupy the town and abandoned campsite. But there was no order to pursue the retreating Government army. Elcho's troopers followed them, but from a respectful distance. It is understandable that Charles and his commanders probably felt they didn't have enough of a coherent force left to mount a pursuit.

So this looked like more of a default victory. The one side saying they had completely captured the empty town and the other saying they were going to check out anyway to go back to Edinburgh and change their wet clothes.

I think Falkirk was a tie. But then, as I said up in the intro, I don't have a dog in that fight.

Wargaming Falkirk

But there are some factors I think should be considered:

1. Relative Firepower

Because the Government regulars were highly trained in disciplined platoon fire, they should be rated at the very highest of 18th century fire combat rules. They were also using prepared cartridges (about 24 rounds issued per man) which would have increased their rate of fire (between 3-5 rpm) and minimized misfires. Bailey cites a 20% misfire rate (one in five) because of the rain, but statistically, this was not much worse than the ordinary 15% misfire rate for the muskets of the period. So I would only slightly depress the fire algotrithm for weather.By contrast, the Jacobite troops were generally not supplied with cartridges for their muskets, but loaded them tediously, pouring an unmeasured amount of powder down the barrel and some into the pan.; as when they took their pieces hunting. They tended to fire off only one round at the beginning of an engagement, then drop their muskets, pull out their swords, and charge. The wet weather would also increase the misfire rate, though, assuming the single round, and assuming they would have pre-loaded, you can probably make the misfire 20% as for the Government troops.

2. Ground

The surface of the Falkirk Muir was apparently quite pockmarked with holes dug by people "mining" peat. It was also quite soggy. So this would have slowed movement, and restricted horse to a slow trot. Guns would be stuck quickly, unless you have a what-if scenario in which Capt. Cunningham had adequate crews and teams to pull his guns up the hill.Since the muir humped in the middle, the visibility from north to south would have been blocked by the crest. So units on the southern slope would not be able to see what was happening on the northern slope.

3. Visibility

4. Discipline and Morale

The training and discipline of the Government regulars (combat efficiency) should be considered high. Their morale would, however, be somewhat unsteady considering the ferocious reputation of the Highlanders in battle and the previous embarrassment at Prestonpans.

For the Jacobite player, discipline of his regiments should also be considered fairly high (witness their holding fire at the beginning of this battle and their ability to maneuver deftly). They should also be considered very confident vs their enemies, their sense of the righteousness in their cause, their contempt in the hand-to-hand combat abilities of their enemies, and again remembering their quick and overwhelming victory at Prestonpans. However, once a Jacobite regiment is disordered (through retreat or combat) it should be considered very difficult to reform (a higher die roll or chance card?). As the Regulars used drums to reform and recall after combat, the Scottish regiments used bagpipers. But the pipers also considered themselves frontline warriors; they usually dropped their pipes when the charge started, took out their claymores, and joined their mates; so they were not available to sound a rally or recall.

5. Hand to Hand Combat

This is the one area where Jacobite units would be considered superior to their Hanoverian counterparts. The claymore, targe (little leather shield), and the dirk of the Highlander made them formidable in close combat. Though the British regulars were issued with swords, these were frequently left in camp as they were considered encumbrances. Most combats were decided by fire (at least on the Continent, against the French); it rarely came to hand-to-hand combat. And they weren't trained to sword fight anyway. The musket and bayonet were, in practice, feeble defenses against a berserker Highlander's broadsword, and the little targe was used to smack away the bayonet (in the same way that Shaka Zulu had trained his army to use their shields against the spears of their enemies--see my article on Isandlwana 1879 and Gqokli Hill 1818). The Duke of Cumberland, in preparing his army prior to the final Culloden campaign, changed the bayonet training of his infantry so that each man in line would thrust at the enemy diagonally to his right, on the unprotected side, relying on his left-hand mate to take care of the Highlander in front of him. This new fighting method proved much more effective at countering the Highland charge at Culloden. But at Falkirk, this new countermeasure wasn't practiced yet.

|

| Back of the little, leather shield, or targe, used by a Highlander,. who would usually also hold a stabbing knife, or dirk in that hand. |

What If Scenarios

2. Leave John Drummond's Lowland division with his cavalry to the north and directly opposite the Government camp, fixing that flank.

3. Warmer, drier weather. Let both sides bring up their guns.

4. Let the Jacobite player make a wider encircling move to the south, coming up on Falkirk from the southeast, threatening Hawley's communication with Edinburgh.

5. Delay the Jacobite move so they arrive to the south of Falkirk after sunset, keeping the fixing force under Drummond at Larbert. This would attempt to repeat Prestonpans.

Orders of Battle

Command

In this column I have listed the regiments in the color of their uniform

coat. With the Jacobite commands, since they would have been in their

own "civilian" coats and tartans, I've coded them in a generic brown. For the Government regiments I have also named them in their eventual 1751 numerical designation, but in this period they were known by their colonel's name.

Facing For the Government (or Hanoverian) Army this column is coded in the facing color of the particular regiment. Since the Jacobite units didn't have official facing colors that I could find, I have coded these in the national blue of Scotland, which many of their bonnets would have been. I have also labeled each unit with its military symbol.

Flags for the government regiments are rendered for both the colonel's and regimental flag, which field was usually in the facing color of the regiment. For Jacobite units I have rendered the flags as far as I could research them. Since most were captured at Culloden three months later and burned, some of these may be more speculative than others.

Tartans These patterns are based on ancient patterns, which were dictated by the weavers in the region that the clan inhabited, and not on any legal livery of the clans at this stage in history. One of the re-enactor sites I looked at claimed that it wasn't until the 19th century that tartans were regulated, so the Jacobite soldiers may not have had a uniform tartan per regiment.

Strengths These are obviously approximate. Of the various sources I found, these numbers vary considerably (see references below). Since this battle involved psychological factors, and since the relative total numbers were more or less equal, the exact returns probably don't matter for the purposes of a wargame.

Ranks In the British Army, the standard deployment called for three ranks for foot, and two for horse. Hawley, in his tactical directions to his army, describes the practice of the Highland foot to deploy in four ranks (same as the French), with the first rank manned by the best-trained and armed troops (with muskets, swords, and targes) and the subsequent three ranks armed indifferently, sometimes with only pitchforks and other farm implements, but not necessarily with muskets, pistols, or even swords. Hawley also describes the Highland formations ask condensing into 12-14 ranks as they charged, though by this time, the term "formation" hardly applies so much as "mob". However, both Bailey and Duffy describe the Jacobite infantry as deploying on three ranks, as their enemies.

References

Bailey, Geoff B. Falkirk or Paradise: the Battle of Falkirk Muir, 17 January 1746, 1996 John Donald, Edinburgh. ISBN 0859764311

Duffy, Christopher, The '45, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Untold Story of the Jacobite Uprising, 2003, Cassell, ISBN: 9780753822623

Harrington, Peter, Culloden 1746, Osprey Campaign Series #12, 1991, ISBN 1-85532-158-0

Nosworthy, Brent. The Anatomy of Victory: Battle Tactics 1689-1763, 1990, Hippocrene, ISBN 0-97052-785-1

Reid, Stuart & Hook Richard, British Redcoat: 1740-1793, 1996, Osprey Warrior Series #19, ISBN 1-85532-554-3

Online References

Historic Environment of Scotland, Battle of Falkirk II BTL9,

Nevin, Michael https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HNZIeaKKjCs

interesting lecture about the battle by scholar and chair of The 1745 Association

Dennison, Deborah, Battle of Falkirk Muir 1746 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O359XMwZh38

Here is glorious aerial view over the battlefield, taken directly above the monument and the ravine (I assume with a drone) on Google Street View. Obviously it is no longer in the condition it was in in 1746, but you can see the topography pretty clearly. Since none of the contemporary maps refer to trees on the moor but do in other parts (e.g. the Torwood), I would assume that none of the trees in this view would be there in 1746. And Falkirk town would be much smaller, obviously.

Thanks for another excellent battle post Jeff. The background info is very useful and threw up a few things I didn't know about the '45. Keep up the good work!

ReplyDeleteThank you right back, Steve. I really appreciate your readership.

DeleteSuperb article, thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you, as well, Jubilo. It feels good to know that other people like these as much as I like doing them.

DeleteGreat read Jeff, the Jacobite rebellion is for me quite a blind spot... Outlander notwithstanding :)

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting that the British "Wolfe" commander was James Wolfe, probably the youngest commissioned officer in the British Army ever. It would be very cool to see your treatment applied to the battle of the Plains of Abraham, just because of... serendipity?

Thanks for the compliment, sir. I'm glad you liked it.