Chickamauga

American Civil War

Sunday, 20 September 1863

Rear Guard, Army of the Cumberland under George Thomas: 10,765, 16 GunsLeft Wing, Army of Tennessee under James Longstreet: 13,948, 13 Guns

Weather: Overcast but dry. 87⁰ (30 C) at 15:00 on the 20th. Nights it got down to freezing. Also there had been a drought for some weeks and other than the Chickamauga Creek, the gullies and streams were dry.

Sunrise: 06:28 Sunset: 18:42 End of Twilight: 19:07

Moon in its first quarter. At zenith at 19:01, set at 00:12

( U.S. Naval Observatory from date and coordinates)

Geo Coordinates: 34° 55′ 12″ N, 85° 16' 12″ W

Hodor of the Civil War

I've been meaning to do an article about this closing act of the Battle of Chickamauga since I started this blog six years ago. Snodgrass Hill was where my great-great grandfather, John Fletcher Hill, fought in a near-suicidal rear-guard action against the onslaught by a victorious Confederate army. I wanted to honor him and the handful of incredibly brave Union soldiers who did this heroic thing.I won't relate the entire three-day battle of Chickamauga (at least in this single post). In many ways that horrific battle was even more complicated and bloody than Gettysburg, which took place a little over two months before. And, for those of you fussbudgets who are still bothered by my increasingly misnamed blog, aside from Gettysburg, Chickamauga was probably one of the most unobscure battles in the Civil War. And one of the most thoroughly documented. But I wanted to zero in on the final hours of the heroic last stand by a few, forlorn and, in the end, forgotten defenders who held off the victorious Confederate hordes of Braxton Bragg while their comrades made their escape.

In many ways it is the same story of Hodor in Game of Thrones.

Much larger maps below. Read on.

But first, a little background.

As I said, I'm not going to cover the entire three-day Battle of Chickamauga in detail. At least not in one post. For that I would highly recommend either Peter Cozzens' This Terrible Sound or David Powell's quadrilogy, The Chickamauga Campaign, both works of a lifetime for these authors. But I will bring you up to speed on how we end up on Snodgrass Hill, this battle within a battle.The days from the 18th to the 20th of September 1863 next to Chickamauga Creek (appropriately enough, translated from the Cherokee as either "Dead Creek" or "Stagnant Creek") was one of the bloodiest and most mismanaged battles of an already bloody and mismanaged Civil War. While the technical victory was given to the Confederates because they held the field at the end of the day Sunday, both sides lost pretty equally, suffering tens of thousands of casualties (about 16,000 each out of a grand total of 124,000 engaged, almost a third). The victory was truly Pyrrhic for the South as Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee never really recovered and he wouldn't achieve his aim of recapturing Chattanooga. Meanwhile, the losers, William Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland, rebounded stronger than ever and within two months resumed their march on Atlanta (without Rosecrans, however, who was sent to Missouri to "spend more time with his family").

|

| William Rosecrans C-in-C of the Army of the Cumberland A very religious man. |

Having driven Bragg's army completely out of Tennessee by the beginning of September, seizing Chattanooga, and crossing the Tennessee River, Rosecrans assumed he was just going to continue more of the same, pushing a dithering Bragg farther and farther back into Georgia. Confident that Bragg was already on the back foot, Rosecrans spread his five corps out (four infantry and one cavalry) to secure the passes through the long geological feature called Missionary Ridge on the Georgia side of the Tennessee River. What he hadn't counted on was Bragg himself moving over to the offensive to try to cut him off from Chattanooga and his lines of communication. He had just assumed that Bragg, playing his previous role, would just continue to retreat all the way to Atlanta.

Rosecrans also apparently discounted dire intelligence warnings from Washington that Bragg was getting significant reinforcements both from western Mississippi and Virginia, the latter when Jeff Davis persuaded Lee to lend James Longstreet and two divisions of his veteran corps to the beleaguered Bragg. It would not be the first time that a commander in the field dismissed intelligence (said the former intel officer).

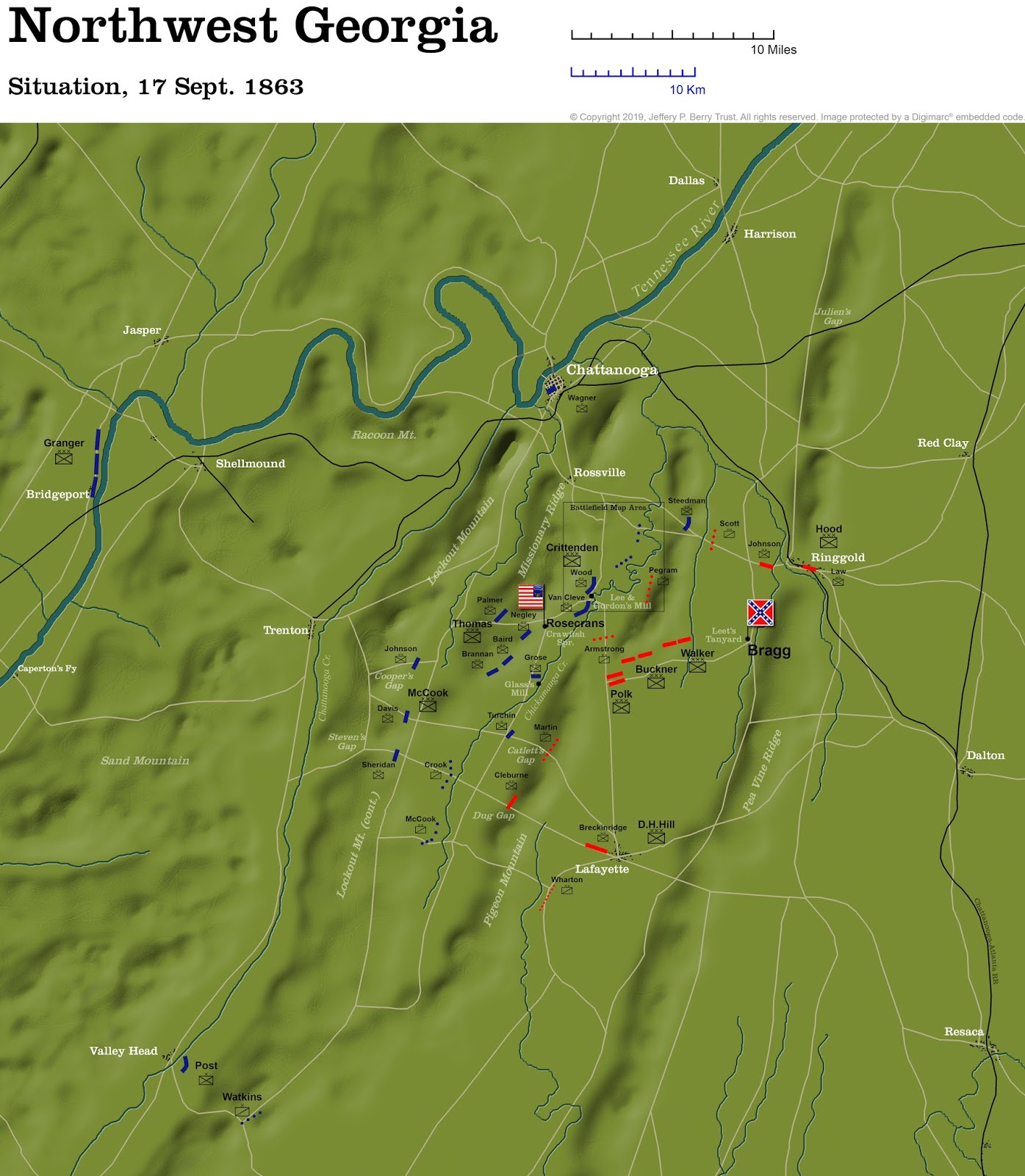

Up until the 17th the Army of the Cumberland had been dangerously spread out along an almost forty mile front from Chattanooga southwest to Valley Head on Chattanooga Creek. Meanwhile, Bragg was concentrating his newly reinforced army (now numerically stronger than Rosecrans' force: 64,838 to 58,805) along the lower Chickamauga Creek with the idea of striking Rosecrans' left and cutting him off from his lines of supply to Chattanooga. It was to be a classic Napoleonic (or Frederickan, depending on your bias) Manoeuvre sur les Derrieres--a term which always struck me with uncomfortably proctological connotations.

Great in theory. But in practice, as in so many good plans, a cluster-[expletive deleted].

A general map of the strategic situation the day before the battle. A note on shadows: I have received some complaints that the shadows in my maps are confusing because hills look like valleys. Conventionally we are conditioned to view a light source from the upper left, but in my maps I have assumed the sun was shining more-or-less from the south, as it tends to do in the northern hemisphere, or bottom of the image (except in my map of Isandlwana, which was in the southern hemisphere). So, in looking at these maps, think of the light coming from the south.

Rosecrans was aware that something was up. He ordered his cavalry commander, Mitchell, and Gen. Granger to send one of his Reserve Corps divisions (Steedman's) east toward the railhead at Ringgold to probe for Rebel activity. Steedman indeed ran into quite a lot of Rebel activity in the form of Bedford Forrest's cavalry and the detraining divisions of Longstreet's corps, which were starting to arrive from Virginia.

Across the Chickamauga Creek, Union cavalry under Minty and Wilder's mounted infantry reported more Confederate infantry and cavalry attempting to cross. These two brigades held back the Southerners for much of the 18th until they were eventually driven back by overwhelming force. Rosecrans, with the northern wing of his army at Crawfish Springs, sent urgent orders to his spread-out army, particularly McCook's XX Corps, to hurry north and converge on Lee & Gordon's Mill in anticipation of a Confederate turning attack between his left flank and his base at Chattanooga (see strategic map above).

|

| Braxton Bragg C-in-C of the Army of Tennessee Hated by all who served under him. In fact, only loved by Jefferson Davis who evidently thought he was maligned. |

While Bragg's plan was good, its execution was, shall we say, oh...what's the word for the opposite of good? His forces started crossing the Chickamauga during the evening of the 18th, and by the 19th he had four corps on the west bank, ready to strike Rosecrans' flank while most of his army was still hurrying north.

But communication between the various commands in the Army of Tennessee was that same word that was the opposite of good. Commanders openly despised each other and talked trash about one another like middle-school mean girls. Bragg himself was held in varying degrees of contempt by nearly all of his corps commanders. So the timing and coordination of the attack on the 19th was off and slow. Some commanders refused to act until they had breakfast first. And Bragg's aides galloped all through the woods, issuing attack orders to every clump of troops they happened to stumble across. The disorganization of the Confederate army was its own worst enemy.

Because of this lack of coordination on the Confederate side, Rosecrans, sensing his peril almost too late, had just enough time to pull his army together along the Lafayette Road to the west of the Chickamauga Creek. (see overall situation map of the whole battle below). All day and into the evening both armies murdered and maimed each other in the thousands as division, brigade, and regiment collided blindly in the woods, often firing into friendlies, mistaking them for the enemy. Both Cozzens and Powell, in their phenomenally monumental works on the battle, narrate every single engagement during these chaotic three days in excruciating detail (if you're that interested), but suffice it to say that it was a nightmare of mismanagement and confusion. Mostly, the Army of the Cumberland was just trying to shore up its line along the LaFayette Road and keep from being flanked, while Bragg's army was trying to feel for where the Yankees were in the smoke-filled woods.

By the night of the second day the now outnumbered Union army had managed to consolidate itself behind a continuous, fortified line along the Lafayette Road and had held off the disjointed Rebel attacks, which had continued until long after sunset.

Rosecrans felt that he had dodged a bullet and liked his prospects for surviving, perhaps even getting Bragg to exhaust himself again on the 20th so the Rebel would give up and resume his retreat to Atlanta. The Confederate command-and-control disaster saved the Union, at least temporarily. But Rosecrans was to have his own communications problems, which would prove fatal by the end of the third day.

Bragg makes a new plan, tells no one, and goes to bed.

That afternoon of the 19th, about 16:00, Longstreet and the remainder of his troops (at least his infantry; there had been delays with the artillery and the horses) arrived at Catoosa Station just outside of Ringgold after a 965 mile, round-about train ride from Virginia and moved up to the assembly area on the south flank of Bragg's army. Longstreet spent hours looking in the dark for Bragg. Nobody from Bragg's staff had been sent to meet him at the station and nobody he ran into knew exactly where Bragg's headquarters were. Eventually, about 22:00, Longstreet found him at Thedford Ford on the east bank of the Chickamauga. He had to wake up the old man to get his orders.Prior to Longstreet's arrival, Bragg had had the brilliant idea to reorganize his army--in the middle of a three day battle,. He was going to give his favorite corps commander, Leonidas Polk, the northern wing, with around 20,000 men of the survivors of that day's fighting, and Longstreet, with some 23,000 the southern wing. In the reorganization, divisions were willy-nilly reassigned to the two wing commanders, effectively rendering their original corps commanders redundant (D.H.Hill, Walker, Buckner). The plan was for Polk to launch a pinning attack at dawn against Thomas' stronger, northern wing of Rosecrans' army, dug in around Kelly Field. Then, when Rosecrans was rushing reinforcements from his right wing to reinforce Thomas, Longstreet was to attack en echelon in a powerful killing blow that would break through, wheel south, and gobble up half of the Yankee army. Bragg told Polk in person of his new plan, but Bragg's staff didn't write it down, and he didn't bother to tell D.H.Hill or the other corps officers of the new command structure, or his plan. He just assumed Polk would convey it to his fellow corps commanders that he was their new boss. Then Bragg went to bed.

Moxley Sorrel and Peyton.Manning (I know what you're thinking, but no relation). Longstreet proceeded to ride around the dark woods looking for the division and corps commanders in his new command (Hood, Law, Kershaw, Hindman, Preston, Buckner, Johnson, Stewart), to try and get them to understand Bragg's new plan and make sure their troops were in position, provisioned, and ready to go at first light. One by one he found them and issued orders for their positioning and the next morning's attack. While so many of the Army of Tennessee's commanders hated each other and Bragg, Longstreet's reputation as Robert E. Lee's right hand had proceeded him; many knew him from West Point, and they were mostly enthusiastic that, at last, their fortunes might have changed with his arrival. Here was someone who knew what was what.

Breckenridge spent the night around Polk's campfire, but he later insisted that the subject of the dawn attack, in which he was supposed to play a major role, never came up. And though Polk apparently sent a lone messenger to D.H.Hill advising him of his new authority over him (which would have thrilled Hill, who despised the bishop), that messenger got lost and couldn't find Hill. The trooper also never reported back to Polk of his failure to deliver the message. It took one of Polk's staff officers who happened to find the hapless cavalryman sitting by a fire roasting marshmallows with some pickets to find out that Hill never got the message. The trooper said he got lost. Polk didn't follow through. The "fightin' bishop" went to bed to get himself a good night's sleep.

Night of the Living Dead

Both Cozzens and Powell in their comprehensive works on the battle describe that night as hell. The confused battle in the woods the previous day had started quite a few fires in the dry underbrush of the woods, so that hundreds of wounded men were roasted to death, their comrades unable to get to them. Witnesses describe the horrible sounds of men screaming in agony for help as they burned alive. "Oh, if only I could drown out this terrible sound," wrote one soldier in his journal. It must have been like a scene from Dante's Inferno. Not only that, but in spite of the fires, and the fact that it was summer, the temperature had dropped down to freezing by midnight and many of the men had no blankets, having dropped their packs before going in (as was the practice). So while they were stripped for action, they were ill-prepared to endure the unseasonable frost. Finally, to make matters worse for the Federals, there had been a drought in this part of the U.S. for weeks and all the creeks, except for the big ones like Chickamauga, were dried up, leaving no water to quench the men's thirst after hours of biting cartridges and choking on gunsmoke. Detachments were sent far back to the few known ponds closer to Missionary Ridge to fill canteens with brackish and bloody water. One regiment, the 39th Indiana Mounted Infantry, took it upon itself gallop back and forth between the front line regiments and the far springs with filled canteens. The whole army was thankful to these Samaritans.Unable to sleep anyway, the Yankees did what they always did: They instinctively gathered wood, dismantled rail fences, cut down trees, and piled up breastworks. By this stage of the war the men didn't need orders to do this; experience had taught them to automatically fortify wherever they were halted. The Confederates not so much, though a few threw up hasty log piles during the night. Theirs was the job to attack, attack, attack. So breastworks were a waste of time to them. At least in 1863. That would change too by the next year. But to many freezing on the ground on the Confederate side, the sound of thousands of Yankees chopping wood gave the chill an existential dread.

Comes the Dawn: Nothing.

Eventually the night of hell passed, the last of the screams from the burning men mercifully stopped, and the dawn came. Bragg woke up early back in his headquarters near the Alexander Bridge (see overall situation map below), expecting to hear the thunder of guns from Polk's attack. Nothing. A few mockingbirds maybe. But no gunfireBy sunrise the whole Union line was dug in and strongly protected, gun batteries sighted to give crossfire support. A large battery was mounted on the ridge behind the main line to give extra artillery support anywhere it was needed. The Army of the Cumberland was ready and confident. Let the Rebs come at them; they'd chew them up and spit them out.

Longstreet had assembled his assault force, almost 23,000 men in seven divisions stacked up in echelon, ready to smash into the Federal left. It was to be an overwhelming series of trip-hammer assaults, directed at what was understood to be the hinge of the Union lines, Brotherton Field, This time, though, there wouldn't be a banzai charge across mile-wide open field as there was earlier that summer at Gettysburg; it would be a surprise attack out of the woods, supported by a diversionary attack up north by Polk. It was to be a classic Napoleonic coup de main, reminiscent of Austerlitz. All Longstreet was waiting for was gunfire to the north and a message from Polk that his wing was fully engaged, pinning Thomas on the northern flank.

But by 07:00, then 08:00, then 09:00, still nothing from Polk. It was all quiet on the northern front. Bragg was wondering too what was holding Polk up. He had been explicit, or so he thought, that the attack was to start at dawn, 06:28. He sent an aide to find out what the hold up was, and the aide (who was one of those officers who despised Polk and made up most of his story as calumny) reported that he found the bishop-general leisurely eating breakfast and reading a newspaper. When the aide wanted to know why the wing commander had not begun his attack at dawn, Polk replied that he thought the order to attack had been for when his men were fed and ready (it hadn't), which they weren't, and besides, he hadn't been able to find D.H.Hill to give him his orders. Hill, for his part, complained that he was not aware of any attack order, or any order from Bragg subordinating his divisions to Polk (the two also hated each other). It was a case of grown men with grave responsibilities over the fate of thousands acting like petulant first graders, all pointing fingers at each other.

Finally, wiping his mouth and getting up from his breakfast at 09:15, Polk issued his formal attack orders to Breckenridge to begin the attack with his division. Breckenridge's brigades, who had been up, muskets at the shoulder, in line, and ready to go from dawn, started moving at 09:30. And the second day's battle was finally off, three hours late.

Not that things were any better on the Union side.

While the coordination of the Confederate army was abysmal, things weren't any better on the Union side. Ignoring his own army's chain of command and disrespecting two of his corps commanders (McCook and Crittenden), Rosecrans kept issuing contradictory orders directly to divisions and brigades. Pull out and move north to reinforce Thomas, move up to support so-and-so, and so on. Then he had the unfortunate habit of berating his subordinates in front of their colleagues and men for disobedience or being thick-headed. Not the most inspiring behavior in a leader.

At day break, the Union line was pretty solid from the Brock house up to the north side of Kelly's Field. Thomas had strong defenses and ample reinforcements in the north, plus interior lines (see situation map below), and Rosecrans had moved Wood's, Davis', and Van Cleve's divisions to shore up the right flank. Then came another, contradictory order from Rosecrans that caused all hell to break loose.

As Breckridge's attack on Thomas' defenses in the north got under way at 09:30, Rosecrans got word from a returning staff officer, Kellogg, who had happened to pass by the lines on the right flank (opposite Brotherton field) and mistakenly perceived a dangerous hole in the line there. He had been under the impression that Gen. Brannan, who had been holding the line opposite the Poe Field, was pulling out to move north to support Thomas. As he had passed by Bannan's position, he failed to see his troops lying down in the woods. When Kellogg got back to headquarters he breathlessly reported this danger to Rosecrans. This was followed by another staff officer galloping in from the same direction, reporting the same thing, "a chasm in the line" he called it. The Commanding General was alarmed and furiously wrote a hasty order to Gen. Wood to pull his division out of the line and move it north to plug the gap. When Wood got the order he was confused. There was no gap in the line to his left; Brannan's division held that sector and Wood was still in contact with him. What was Rosecrans talking about? He pointed this out to Rosecran's staff officer delivering the order, Lt.Col. Starling, and Starling said, "Well, then there is no order." Whatever that meant.

McCook, who happened to be standing next to Wood (not his corps commander, but that day without a command himself and just riding around visiting, causing trouble) advised Wood that he had better not question Rosecrans again and obey the order. Both generals had that very morning been severely reprimanded in front of their own staffs by Rosecrans for questioning his orders. Wood, realizing that obeying the order would have the unintended effect of opening a gaping hole in the line, nevertheless told his brigadiers to move their men out.

The brigadiers, realizing the same catastrophic error in the order, protested. But Wood was adamant. Though a good soldier, he had had enough of Rosecrans' ineptitude and abuse and decided to be passive-aggressive at this worst possible time. Starling, alarmed at Wood's news that Brannan was still in place, begged to be allowed ten minutes to gallop back to Rosecrans to obtain clarification. But Wood refused. He ostentatiously brandished the written order to witnesses around him, saying he was glad he had it in writing, and theatrically stuck it in his notebook. According to his own memoirs, and corroborating witnesses, he held up the paper and prophetically said, (are you writing this down?), "Gentlemen, I hold the fatal order of the day."

With this "I'll-show-him!" attitude, Wood doomed the Army of the Cumberland.

For years after the war, everybody involved in this incident had different, and self-serving, memories of it. In Rashomon-like testimony and memoirs, Rosecrans, McCook, Wood, Starling and dozens of people witnessing it, and blamed each other as the bad guy.

It didn't matter, the damage was done. And by this time, the war was long over, and the North had won...sort of.

Coincidentally, at the very moment that Wood started pulling his troops out of the line (about 11:10), Longstreet launched his attack on that very spot. It wasn't from any grand design, or brilliant tactical sense that Longstreet attacked there and then; it was just luck.

Longstreet punches air.

Actually, Longstreet himself hadn't exactly ordered the attack to commence then. He had been waiting for Bragg to give him the go ahead. The idea was that before Longstreet would launch his own assault, Polk's battle on the northern flank would be fully developed, to both pin Thomas and draw more strength from the southern end of the Union army. But about 11:00 Longstreet started hearing inexplicable firing to his right front. Was that Stewart's division attacking without orders?Apparently, like Rosecrans, Bragg didn't feel it was important to use his chain of command; he sent orders directly to all divisions to start the attack. This was not the way Longstreet was used to dealing in the Army of Northern Virginia, where strict chain of command was respected, from Lee all the way down. So he was a not a little miffed. In effect, Bragg created these two new wing commands in the middle of the battle, confusing and pissing off everybody, and then proceeded to ignore them and issue orders directly to the division commanders. But Longstreet was a disciplined soldier so he went around and got his supporting divisions in motion (save Preston's which he wanted to keep in reserve). He reached some when they were simultaneously getting orders from one of Bragg's busy bees.

Unfortunately for Rosecrans, this sudden, overwhelming attack hit him where he wasn't, and proceeded to roll up the whole Federal army south of Kelly's Field. Individual brigades, regiments, and even clumps of soldiers tried to make stands in Dyer Field and on the ridge above that field, where Crittenden had amassed most of his corps' artillery. According to Bragg's plan, Longstreet was supposed to wheel south and gobble up the right wing and depot of the Union army. But that army was, for the most part, retreating in the other direction, north, toward the high ground around Snodgrass farm. Most of them didn't stop there but kept on going toward the Rossville Gap and Chattanooga beyond.

On the northern wing of the Union army, however, Thomas's salient was holding firm. Polk's blows had been hitting futilely against his entrenched men, the Confederates taking horrendous casualties for their efforts. There had been some near breakthroughs, particularly on the left, but there the Yankees had held.

The following map lays out the approximate positions of the brigades and divisions in both armies late in the morning of the 20th, the third day of the battle. Note that many of the Union brigades were in motion, with a general flow toward the north to reinforce Thomas around the Kelly Field. It was about this time, too, that Wood got his fatal and misread order to pull out of the line and move north.

The aptly named "Dyer Field"

As Longstreet's brigades chased the fleeing Yankees from the woods along LaFayette Road into Dyer Field, they ran into a raggedy line of Union troops behind an intimidating array of batteries on the hill (see map above). Fleeing Union infantry were swarming the field and masking their own artillery when Longstreet's troops emerged from the woods close after them, so there was hesitancy on the part of the Federals to fire. In the first place, they couldn't tell if the troops in the distance, at the wood line, were friendlies or not because they were wearing blue. As I mentioned earlier, on their way out west from Virginia, Longstreet's men received a requisition of brand new uniforms, which, due to some ordering error, had been dyed dark blue, with new pants of light blue, just like Union troops. The Confederates, their old, smelly rags falling off of them, gratefully donned the new blue uniforms. But the consequence was that from a distance, they looked like Yankees. This had already caused friendly fire mistakes during the battle.

The Federal regimental commanders rallying their infantry behind Crittenden's batteries had their flag bearers wave the national colors to get an answering signal from the unidentified blue infantry at the bottom of the hill, to ascertain if they were friendlies. The advancing Confederates (in this case, Perry's brigade from Law's division, Hood's corps) took the sign as a taunt and charged up the hill. The Federals, still unsure if these troops were friendly, held their fire until it was too late and the advancing "bluecoats" unleashed a volley first, removing all doubt which side they were on. The Union guns had only time to let go a single round before they were overrun and their supporting infantry routed again.

- Why is Dyer Hill aptly named? Well, because of the "dying" error that caused the Confederates to look like Yankees. And the scene of hundreds of more dying Americans, of course. And that it was the scene of "dire" consequence that the Union army could hold off a complete rout. I know, bad puns. But I couldn't resist. And the Dyer family, whose farm was ruined, probably wouldn't have been amused.

The battle following Longstreet's breakthrough was complicated (as had been the whole three day battle until now), and I could write another whole narrative covering the action in Dyer Field alone. There was also more fighting going on around the Kelly Field salient, where the Union brigades were holding their own. And while the Union army was in retreat on its southern flank, it was by no means a complete rout. Some regiments bolted, others held their ground and gave as good as they took, retreating slowly in the direction of Snodgrass Hill. The "victorious" Rebels were themselves taking terrible casualties all during this phase of the battle, moving slowly forward and frequently falling back.

Rosecrans, by this time, had pretty much given up and personally left the field, galloping as fast as he could back to Chattanooga. He and his staff were taking the west road through Missionary Ridge through McFarland's Gap, missing Granger and his, as yet, uncommitted Reserve Corps at Rossville. At one point the commanding general had voiced his half-hearted second-thoughts to his chief of staff, James Garfield (the future president), that maybe he ought to turn around and organize the retreat. He was probably wanting validation for his flight. Garfield, probably sensing this, advised him to save himself and get back to Chattanooga where he could see to the defense of the city, while Garfield volunteered to return to the battle and coordinate an orderly retreat with Gen. Thomas' help. Garfield, who probably knew Rosecrans better than anyone, realized that the commanding general would only make things worse by staying, as he had mismanaged the battle until now. Rosecrans, with evident relief, saw the wisdom of it and left Garfield behind.

The Rock takes charge.

General George Thomas, who seemed to have been the only corps commander in Rosecrans' army to have kept a cool head, was now commanding general on the field. Though many in the army and in Washington felt that he should have been given the Army of the Cumberland to begin with, unlike other generals on both sides, he was not political or contentious. He followed orders. He respected his commanding officer and remained loyal to Rosecrans, even after the defeat at Chickamauga. Unlike nearly every other Civil War general, he wrote no memoirs and so we don't know what his personal opinion of Rosecrans was; Rosecrans was his commanding officer, and that's all he needed to know. He kept his priorities with the safety and success of the army. A soldier's soldier.

At the beginning of the war, unlike his fellow officers from Virginia, Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart, Thomas elected to stay loyal to his country over his seceding native state government. Stuart loudly and often said he'd hang him as a traitor if he ever caught him. His sisters turned his picture to the wall and refused the gifts of money he sent them during the war. Though he would save the army at Chickamauga and go on to win some of the most decisive victories in the West during the war (Missionary Ridge and Nashville), he was not honored the way Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Mead, and so many other generals later were. He was a man of principle and integrity. Though his family had been legacy slave holders in the antebellum South, during the war, when he had Black regiments under him at Nashville and saw how they fought even harder than the all-white regiments, he changed his mind about people of color. After the war he vigorously defended the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. As a military governor during Reconstruction, he fought to defend freedmen and other Southern Unionists against the KKK. He also wrote harsh newspaper editorials about how the former rebels had sought to rehabilitate themselves as defenders of an honorable "Lost Cause" for freedom, when in fact, he argued, they were just traitors trying to wash themselves of treason. He didn't mince words. In a lot of ways he was like his adversary on this day, Longstreet (though, unlike Longstreet, Thomas did get a statue or two, a fort named after him on the Ohio River, and a square in D.C.), both good soldiers, both cool-headed, both disinclined to get involved in politics, and both with an uncanny sense of the right thing to do. This extended for each of them through Reconstruction, when both generals actively defended the civil rights of people of color and those Southern whites who had remained loyal to the union.

Thomas had been deftly managing the hard defense on the northern flank around Kelly's Field for two days. Now, as the southern flank of the army caved, he moved his headquarters back 500 yards to the Snodgrass farmhouse. He still kept in close contact with the divisions compacted around Kelly's, which was only a couple of minutes away by horse. He also sent a plea back to Rossville Gap for Gen. Granger to come forward with his Reserve Corps to help him. And for two hours, while he chomped nervously on a cigar, he kept raising his field glasses to the north, looking for Granger's arrival.

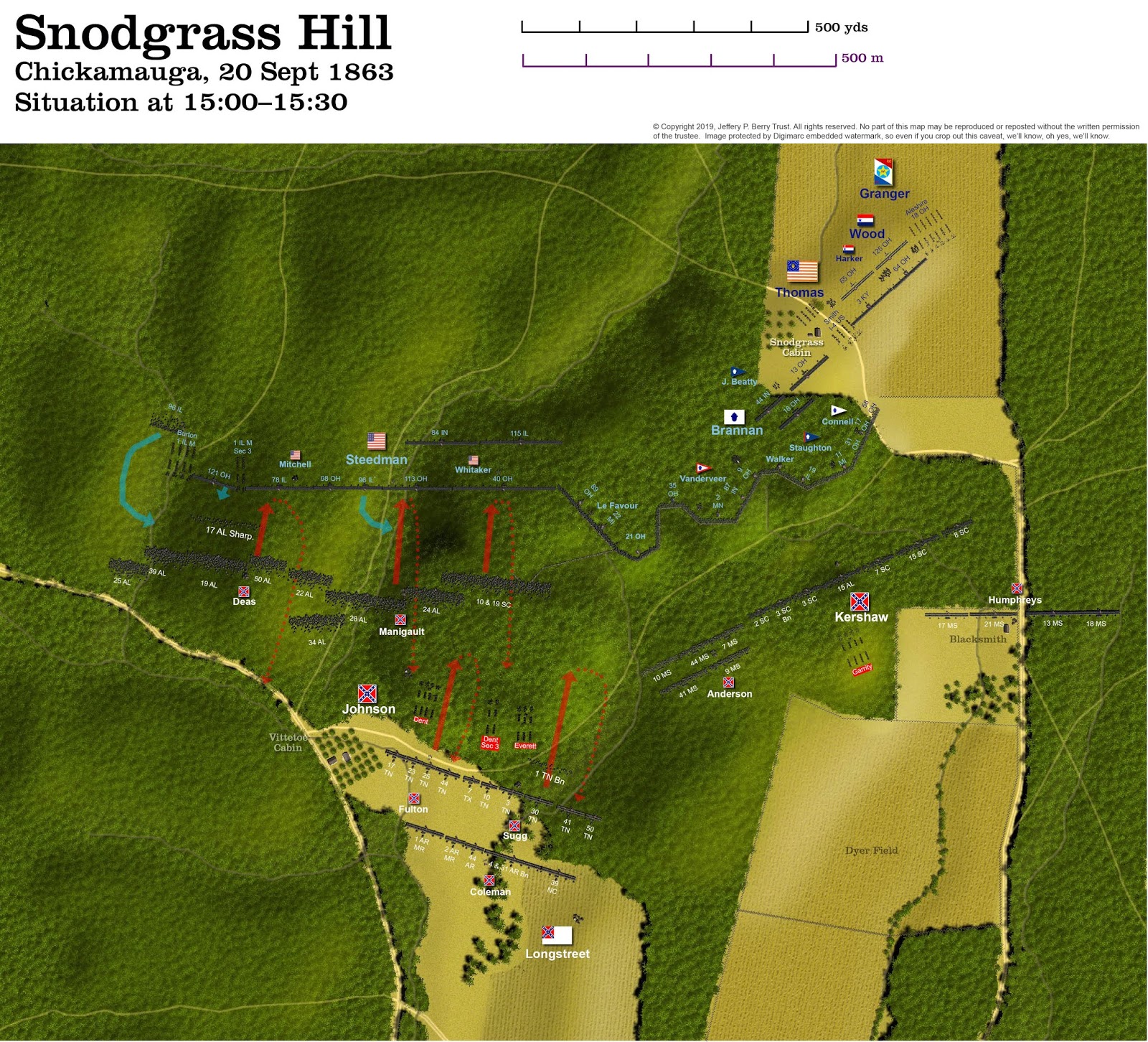

Meanwhile, Thomas cooly managed the defense of Snodgrass Hill (later called, for some unsatisfactory reason, "Horseshoe Ridge"--it isn't at all shaped like a horseshoe--maybe there were a lot of discarded horseshoes littering the ground, who knows? Or maybe it came as a polite euphemism for what the troops were probably calling it, Horsesh*t Ridge. I don't know.). He kept close communications with all available forces left on the field, from Kelly's Field to Horseshoe Ridge and rallied stragglers and commandeered remnants of brigades as they came by. As retreating but still-willing regiments and companies gathered on the hill, Thomas assigned them places to defend and gradually built up an almost impregnable position.

The first unit on the hill was a battery of four 12-pounder Napoleon guns of the 4th U.S. Artillery, unlimbered in front of the tiny Snodgrass Cabin to cover a wide field of fire as far as Kelly's Field to the east and Dyer Field to the southeast. These were soon supported by Harker's brigade of 950 survivors of Wood's division, the ones who were fatefully ordered to pull out of the line, starting this disaster to begin with. These people were in no mood to retreat further. They wanted to vindicate themselves from what they perceived as an unjust order to withdraw.

The Horseshoe Ridge portion of the position, to the west of the cabin, was also extremely intimidating to any attacker. On these three fairly steep knolls (called, imaginatively, Hills 1, 2, and--you guessed it--3), separated by ravines, Thomas and his division commander, Brannan installed various rag-tag remnants of brigades that had been fighting, dying, retreating, and rallying for two days. On the very western side of this line was the rather large 21st Ohio, 510 men of which seven of its ten companies were armed with new, revolving Colt rifles (same principle as the Colt revolver, but in long-arm form), each one able to pump out five rounds in quick succession. Because of the high volume of fire, this single regiment was capable of generating the firepower of a full-strength brigade. Their commander, Dwella Stoughton, lined them up in a single rank behind their makeshift breastworks, extending 350 yards. They were also issued 100 rounds apiece, knowing they would use it up during the course of the afternoon.

These exhausted troops of Thomas's--some entire regiments represented by no more than a dozen men--piled up breastworks along the crest, looking down the slope, their cartridge boxes freshly replenished, and waited for the unnerving banshee screech of the Rebel Yell from the woods beyond. They didn't have to wait long.

Looking southeast from the top of Snodgrass Hill. Smith's battery could rake any Rebels that came out of the woods a little over 100 yards away. And Harker's troops, lying down behind the crest of the hill, would pop up, deliver a volley, then drop down to reload while the four lines behind them fired in turn. It was a very strong position.

13:15 The First Assault

At noon, while trying to rally his divisions in the chaotic aftermath of his breaking the Union line, Longstreet was called back to a war-council by Bragg at his headquarters, two miles to the rear at Jay's Mill. It was the worst possible timing. Polk was also called, even though his wing was in the midst of a highly fluid battle on the right wing. But Bragg felt it more vital now to personally upbraid Polk for being slow to get his attack started that morning. And when Longstreet told him of his breakthrough and how all the Yankees were fleeing north, back toward Chattanooga, and that it was important for his force to swing north instead to bag them, Bragg was incensed. His original plan was for Longstreet to swing south, to drive Rosecrans into a geographical cul-de-sac and trap him there. Longstreet tried to explain that Rosecrans's army was no longer south but north, and that the bulk of the retreating Federals were racing toward Chattanooga. But Bragg groused that nobody seemed to know how to follow orders. Even when circumstances changed. Apparently, it hadn't sunk in with him that in the intervening three days since he'd concocted his plan to come between Rosecrans and Chattanooga, the Federal army was no longer where it had been. So for Longstreet to swing south now would no make no sense. He didn't order Longstreet to adhere to the original plan and, after an awkward silence, the visiting general excused himself to return to his command (in the midst of a battle). But he left Bragg muttering. |

| Gen. Joseph Kershaw Known for his impetuosity, jumped the gun at Snodgrass. |

Sailing on the intoxication of victory, Kershaw felt his division could just sweep over the hill in front of him because the Yankees were quaking in fear. All it would take would be one more little nudge and they'd be off again. Like with the effects of all intoxication, Kershaw's judgment was off.

Almost as soon as they had assembled at the bottom of Horseshoe Ridge, Kershaw ordered the charge and up everybody went. Three thousand men climbed the steep, woody slope. On the way up, regiments lost touch with each other in the undergrowth, alignment within each regiment, or even each company, was a joke.

At first the attackers thought the ridge was empty because there was no fire. Then, suddenly, when they were almost at the top, huffing and puffing, a withering storm of volley fire cut into them. The Federals behind their barricades were aware that there were troops climbing up toward them, but when they came into view, they saw that they were wearing blue coats (the same confusion that had kept the Union batteries from opening up in Dyer Field earlier). But when the bluecoats raised a Rebel Yell, all doubt vanished and the Union men let them have it. The charge by Kershaw's brigade was stopped cold. The Confederates didn't retreat at once but went to ground and exchanged fire with the Federals for a bit. But they had no breastworks and many were caught in a crossfire as they were in one of the ravines that separated the three hills. The Federals, on the high ground and behind works, were hurt little in this firefight. Soon Kerhaw's regiments started crawling back down the slope.

Below, looking up toward the crest of Horseshoe Ridge from where Kershaw's men assembled for their repeated assaults. You can see how steep and broken the climb would have been.

On the western end of the hill, the 2nd South Carolina and the 2nd South Carolina Battalion (I know, Confederate organizational names were confusing) received an especially nasty surprise. After the first volley of the enemy, they felt they had about twenty good seconds to rush the breastworks before the Yankees could reload and fire again. So up they jumped to run up the last few yards. But then a second volley hit them immediately, and a third, and a fourth in rapid succession. This was a disconcerting surprise. As they turned and ran, tumbling down the slope to escape, a fifth volley hit many in the back. They had been up against the 21st Ohio and their Colt revolvers. So it had seemed like they were facing five thousand men. This would replay several times that afternoon as wave after wave made suicidal charges on the 21st.

Farther to the east, where a gap had opened up in the middle of Kershaw's brigade, a newcomer, the 15th Alabama, showed up out of nowhere. Having become separated from its own brigade somewhere back in Dyer Field, the 15th was already known for being a freelancing unit. Its men crowded in between Kershaw's South Carolina regiments and raced them up the hill. When they too were stopped in a ravine by overwhelming fire from above, instead of retreating, the Alabamians just found cover in the rocks and trees and kept up an ineffective counterfire on the ridge above them. The notable thing about this regiment was that it was the very one that had been repulsed by the famous bayonet charge of Chamberlain's 20th Maine on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. These were the survivors of that unfortunate defeat and now they found themselves in almost the same circumstance again, not three months later. One wonders if they thought God had given them a chance to vindicate themselves. Or, did they think, "Not again!"

Finally, farther east, Kershaw's other brigade, that of Humphreys' (formerly Barksdale's, who had been killed at Gettysburg) had marched out into the open field, up to just beyond the edge of the woods bordering the south part of Snodgrass Field. And stopped. There they stood for several minutes, not moving forward or backward. Humphreys saw the four guns of the 4th U.S. battery at the top of the hill, but at first no infantry. He was confused as to how to proceed.

Humphreys' view from the bottom of Snodgrass Hill. Notice how he would have only been able to see the guns to the right of Snodgrass' cabin as Harker's brigade would have been lying down behind the crest. When they stood up to deliver their volley, it must have been quite a nasty shock.

On Snodgrass Hill, the officers of Harker's brigade weren't sure at first, if the men at the bottom of the hill were friend or foe. It was the blue uniforms again. Union troops were still retreating out of the south so the debate was that these might be some of those. But apparently somebody noticed a Stars-n-Bars battle flag and Harker ordered "Open fire!" Then the men of the 3rd Kentucky (Union) and 64th Ohio stoop up from behind the crest and let the blue-coated Rebels have it. At a close range of only 100 yards, the four 12-pounder Napoleon guns of Smith's 4th U.S. battery also opened up with canister. The Confederates did fire back, but since they were firing uphill and at targets which were elusive, they made almost no dent. Humphreys' men took 155 casualties in the few minutes they stood out there in the open before he overcame his shock and ordered the brigade back into the woods, from which he didn't budge for the rest of the battle. It was a sickening and useless sacrifice of these inconceivably brave men.

- Also left behind, tragically, was one Richard Kirkland of the 2nd South Carolina, who had made a name for himself on

both sides as the "Angel of Mayre's Heights" at Fredericksburg when he had risked his life to bring water and blankets to

the dying Yankees suffering on the field that freezing night. His last words to his friends

trying to rescue him on Snodgrass Hill were, "Save yourselves. Please tell Pa I died right." He certainly lived

right.

Both Powell and Cozzens, in their exhaustive narratives of Chickamauga, relate several instances of soldiers on both sides showing kindness to enemy wounded, often at risk to themselves. One Union soldier on the first day of Chickamauga, himself wounded, not only gave a wounded Confederate his own water, but also cleared the leaves away from him so he might be spared the danger of burning alive if the frequent brushfires swept through. The wounded Rebel expressed deep thanks but also surprise because he had been led to believe that all Yankees were evil. These instances gave another meaning to the term "civil war".

|

| Monument in front of the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, PA, to Richard Kirkland, "Angel of Marye's Heights", one of the countless Good Samaritans of the Civil War. |

This was a good plan but, like all plans, something unexpected happened.

Granger to the Rescue

|

| Gen. Gordon Granger |

So he set out to Thomas' aid. By 13:00, when Thomas' messenger had reached him, Granger's men were already halfway down the LaFayette road. As his 3,700 men marched down the dusty pike, they started running into more and more streams of wounded Union soldiers heading north. Nevertheless, they kept on.

Soon this column noticed Confederate cavalry (Forrest's troopers) to their east. Steedman sent out flankers to guard that side of the column--the 96th Illinois even formed square, a rare example of this quaint Napoleonic formation employed during the Civil War. But Granger told them, "None of that, now," and kept them moving; he was not impressed with Rebel "rag-a-muffin cavalry" as a threat. He sent back to Rossville for Steedman's remaining brigade (Dan McCook's) to hurry down and hold off the threat of Forrest's irritating cavalrymen. Steedman, meanwhile, directed his column off the road, to move in the direction of Snodgrass Hill through the woods. That's where Thomas' messenger had directed him.

At 13:30, Thomas, nervously peering through his field glasses toward the northern edge of Snodgrass Field, saw a mass of marching infantry heading his way. Because Granger's men had been marching on the hot, unpaved, country road for a couple of hours, they were covered in dust and Thomas could not make out whether they were wearing blue or gray. And he had been fooled more than once that day by Rebels wearing blue uniforms. Shaking with fatigue and excitement, he handed his glasses to a staff officer to see if his younger eyes could make out their affiliation. After an interminable pause, the officer said, yes, he could see the national flag fluttering above the ranks. They were Granger's reinforcements. And not a moment too soon!

14:15, Third Assault

At 14:00 Johnson, who had his two small brigades of Sugg's and Fulton's Tennesseeans ready to climb up the hill, as well as Anderson's brigade from Hindman's division on his right, ordered the advance. They climbed through the steep ravine cautiously, not sure where the end of the Federal line was. Scores of individual Yankees, unconnected to their original regiments but pitching in on their own, fired at the oncoming Rebels' flanks. This part of the battlefield was completely unknown to Johnson.Then, out of the blue, the Confederate climb ran into a solid mass of blue. Steedman's division, having freshly arrived with Granger to reinforce Thomas, had marched over to the exposed right flank of the Union line and deployed for attack. When they saw the graybacks (unlike Kershaw's men, Johnson's were in respectable Confederate butternut), the lead regiments of Steedman's brigades opened up. After firing their first volley of the war, with bayonets fixed, the 419 men of the 96th Illinois charged down the hill. Granger had earlier remarked to Thomas when he arrived at Snodgrass Cabin that though his men were inexperienced, ignorance of what combat was really like would give them an idealistic courage. "They are raw troops, and they don't know any better than to charge up there."

This sudden surprise of so many furious Yankees was too much for the already exhausted and depleted men of Fulton's tiny brigade. They bolted. On Steedman's left, the 22nd Michigan, also combat virgins, charged into the left flank of Anderson's 10th Mississippi. The 21st Ohio, wary of being outflanked, had already bent back their right and established a new line looking west when Anderson's men came huffing and puffing up the hill. At point blank range the 21st again poured out their rapid fire volleys from their Colts. So the 10th and 44th Mississippi, winded, falling like flies, and now hit in the left flank, just tumbled down back down the way they had climbed.

|

| James Blair Steedman I hope I spelled his name right. |

Bushrod Johnson's whole attack ground to a halt, wavered, and broke. The attempt was the largest yet for the Rebels to take Horseshoe Ridge. Unfortunately, the downhill charging men of the 22nd Michigan and 96th Illinois, ecstatic with their first victory, could not be held back, and were themselves mauled by supporting Rebel infantry or close range canister fire when they ran into Johnson's artillery (Dent's and Everett's batteries). They fell back up the hill in turn, suffering their first casualties of the war. The fun was starting to fade.

On the Confederate right, Kershaw made one last effort to take Hills 1 and 2. But his lack of mobility (remember, his horse was still enroute on the train) meant that he couldn't coordinate all his regiments and only four of the ten regiments in his division got the word that another attack was on. This whole third effort suffered from confusion. On Kerhaw's left, the 2nd South Carolina was suddenly fired on from their left rear by the 7th Mississippi, coming up to support Anderson's lead regiments, and mistaking the blue-coated South Carolinians for the enemy in the smoke. These new blue uniforms were certainly a mixed blessing today.

Kershaw's four participating regiments (2nd, 7th, 15th South Carolina, and the 3rd SC Bn) were beaten back again, taking with them the stubborn Oates and his 15th Alabama, which finally gave up its toehold beneath the parapets of the Union position. Humphrey's brigade, still hurting from its mauling in the open field, didn't move from its new favorite place in front of the blacksmith shop in Dyer Field. And Kershaw's division, having been fighting for three days, out of ammunition, and losing 659 of its original 2,817 (23%) was done for Chickamauga.

15:00, 4th Assault

By 15:00 Hindman had gotten his next two brigades, those of Deas and Manigault, up and ready. Since Hindman had been wounded earlier and wasn't feeling his old self, he handed command of his division over to Johnson, who seemed to know the ground better anyway. Johnson, surprised by the new arrival of Steedman's division to the west of Horseshoe Ridge, decided to have Deas and Manigault outflank the now longer Union line. He also appealed to Sugg, Fulton, Anderson, and Kershaw to lend their weight to an overall assault of over 8,000 men to finally take this hill.But the climb up the ravines and steep slopes broke up the tactical cohesion of the assault again. Regiments and companies got into each others' way, further adding to the difficulty of trying to maintain any semblance of a continuous line on this forested mountain. Within fifteen minutes the whole assault was reduced to an unruly mob. And the going was even steeper the farther west one went. One regimental commander had to actually get off his horse and lead it up.

When the first disorganized regiments neared the crest, they were met again by disciplined volleys from Mitchell's and Whitaker's brigades, now behind breastworks and well under control. The Alabamians and South Carolinians came to a halt about fifty yards from the summit and did manage to fire back, hitting several Union officers, including Gen. Whitaker (whose wound was more of a nasty thump to his belly by a spent ricochet, but which nevertheless convinced him to leave his men to go have it looked at in the rear). But after about thirty minutes of this firefight, the Confederates had had enough and started to melt back down the hill, out of sight. They were encouraged in their retreat by more bayonet charges from the impetuous 96th (they were having such a good time in their first fight) and the 121st Ohio.

Though Granger had brought with him his corps ammunition wagons, the rounds were getting scarcer among the Yankees. The formidable 21st Ohio, with their fast-firing Colts, were nearly out. They had come up onto the hill two hours before with 100 rounds apiece, but with the repeated Rebel charges had all but emptied their cartridge boxes. Detachments were sent up and down the hill to scavenge cartridges from the dead and wounded (Confederate and Union). Granger had given them a supply of Enfield ammunition but the .577 cartridges were just a tad too cozy for the .56 caliber Colt cylinders and had to be forced in. But the forced cartridges posed a significant risk of bursting the barrels when fired. To prevent this, somebody had the innovative idea to fix bayonets on the muzzles, letting the bayonet's ring hold the barrels together just enough to keep them from bursting. Moreover, one other problem with the Colts was that, owing to their rapid rate of fire, they became too hot to handle. And the men didn't have any water to drink, much less to cool their weapons.

For this particular charge, however, the 21st, and their neighbors to the east, were spared since Anderson and Kershaw had had enough and were sitting this one out. The 21st and 89th Ohio and 22nd Michigan did fire some enfilading volleys into Manigault's right-hand regiment, which helped persuade it to retreat. Johnson, of course, had appealed to Anderson and Kershaw to join this latest attack, but those brigades had had enough, too, and contented themselves with firing uphill into the smoke-choked leaves, wasting ammunition. Just behind Manigault's attack, Sugg's and Fulton's brigades, now supported by Coleman's (formerly McNair, who was wounded), down to almost half their original strength and running low on ammunition themselves, made a half-hearted climb over the bodies of their brothers, but fell back under the blistering fire from the crest.

16:00, A Lull

Thomas and his division commanders, Steedman, Brannan, and Wood were defending Snodgrass Hill well. Though exhausted and running low on ammunition, the men, even the small companies from previously routed regiments, were holding. Granger, who with his turning over of his sole division to Thomas, was out of a job, occupied himself with his favorite pasttime, helping the artillerymen aim their guns. About 15:45 Rosecrans's chief of staff, James Garfield, arrived to tell Thomas that the commanding general had made it safely to Chattanooga and was rallying the half of the army that had collapsed and fled from the right wing. This information greatly relieved Thomas. His was now a rear guard action to delay Bragg long enough for the army to reform. And he could think about systematically withdrawing himself.Things seemed to have stabilized over in Kelly's Field, five hundred yards to the east. Polk's attack had sputtered for a time to a half-hearted duel between pickets. Since the Kelly position seemed secure, Gen. Hazen asked his division commander, Gen Palmer, if he could move from his reserve status over to extend Thomas' wing at Snodgrass. While there had been no action there, that 500 yard gap separated the two masses and Thomas knew it was only a matter of time before Longstreet, or somebody, discovered it.

But for now, the immediate threat from Longstreet's wing seemed neutralized. Four attacks had been beaten back and the Rebels were quiet. Thomas imagined that they too must be spent and nearly out of ammunition. It was a welcome lull. What little ammunition that was left was distributed, and at 16:00 Hazen brought his welcome brigade to help bridge the gap to Kelly's Field.

But Longstreet wasn't nearly done. At 15:00, as Johnson's attack was getting underway, he received another summons from Bragg to go back and report. When he reached headquarters, nearly two miles away, Longstreet was full of excited energy as he reported the complete collapse of the enemy army, and that he was on the verge of gaining the rear when he took Snodgrass. He urged Bragg to order Polk to attack the Union salient around Kelly's Field again to put maximum pressure on what was left of the enemy army.

But Bragg evidently thought that he had lost the battle. He complained that Polk's men had no more in them and were done for the day. And he wanted to know still why Longstreet wasn't swinging south, per the original playbook. Longstreet was aghast. The Union army was now fleeing north, toward Chattanooga, he tried to explain to Bragg. But the commanding general wouldn't believe it. He must have thought Bragg had lost his mind. He had clearly lost his nerve. This was not what Lee's "Right Hand" was used to.

So Longstreet left Bragg fretting back in the rear and returned to Snodgrass. There he found that Johnson's latest attack had failed and everybody was giving up. The hill couldn't be taken. It was too strongly held. In a moment of supreme aaaaaargh, Longstreet wouldn't believe it for a second.

16:30, 5th Assault

As he rode back to Dyer Field from Bragg's headquarters, Longstreet stopped by Gen. Preston, whose division he had been holding in reserve, and told him to follow him with his uncommitted brigades. Those of Gracie, Kelly, and Trigg, with over 4,000 men, had fought little if any over the past three days and were relatively fresh. Aside from the fact that one of the larger regiments in thus division, the 63rd Tennessee, was composed of men forcibly conscripted from pro-Union eastern Tennessee (there were as many Tennessee and Kentucky regiments in the Union Army) and had experienced one of the highest rates of desertion, Preston's regiments had fought well in the war so far.Gracie's brigade, in the lead, got to the vicinity of Snodgrass first, and before the other two could come up, Kershaw once again overstepped his authority and ordered Gracie up the hill to attack before Kelly or Trigg could get there. Preston was livid. Not only was Kershaw just some other division's brigade commander, but he had presumed to think he could just snatch brigades away from another division for his own purposes. Usurpation, of course, seemed to be the prevailing corporate free-for-all culture in the Army of Tennessee. Every officer felt he had the authority to command any group of soldiers he happened to come across.

The result was predictable. Gracie's regiments had to filter through the immobile men of Kershaw's brigade (which, you'll notice wouldn't participate in any more combat that day), which caused them to become disrupted and lose touch with each other. The 63rd Tennessee found itself out in the open of Snodgrass Field, at the foot of the same lethal slope from which Harker's and now Hazen's brigades had savaged Humphrey's brigade three hours earlier. And they met the same fate; ripped to shreds, unable to effectively return fire, and driven back into the woods.

On the left, Gracie's other regiments stumbled up the hill, looking for the Union-held crest. While they did this, Col. Oates's 15th Alabama (you'll remember him having ordered Kershaw's brigade into joining a premature charge with it three hours before) now decided to scramble back in retreat right through the upcoming 3rd and 4th Alabama Battalions, wrecking their lines. Oates had just received an order from his original commander, Perry, who finally found his prodigal son, to return to his own brigade. So now, of all times, he chose to obey the chain of command, yelling outta my way to any friendly troops that happened to be in his path.

Thus broken up, Gracie's regiments crawled up the hill in small groups, finally reaching the Federal breastworks, only to be mowed down again as in the previous attacks. They all sank into the ground and tried as best they could to return fire up into the breastworks.

Meanwhile, Preston's next brigade to come up was Kelly's 874 men, the smallest in the division, with just three regiments. His first brigade purloined by Kershaw, Preston ordered Kelly to follow Gracie due north in support. But on their way there, yet another random Confederate officer, this time Gen Hindman, who, you'll remember, was supposed to be resting in the rear with his wound, happened upon Kelly and carjacked his brigade to move to the northwest and attack the section of the line Anderson had failed to make a dent in earlier. So Kelly changed direction and got his regiments up to try and attack Hill 3. With the same effect as Anderson's previous charge. Two of his regiments came rolling back down the hill after suffering horrendous fire from the Yankee breastworks. What's that maxim? To do the same thing over and over again with the same failed result is the definition of crazy. Or stupid.

But Kelly's attack wasn't entirely futile. His third regiment, the 5th Kentucky (CSA), did manage to climb over the breastworks on Hill 3 which had suddenly become empty in its sector. Previously held by the death-dealing 21st Ohio, that regiment had finally run completely out of ammunition and had withdrawn to the rear to wait until it could be replenished. Kelly's attack had come at the worst possible moment for the Yankees. So the Secesh Kentuckians were able, for the first time that day, to seize the breastworks of one of the hills on Horseshoe. But they couldn't hold it long. Receiving a crossfire from both the 35th Ohio on their right and the 22nd Michigan to their front, they soon had to give up their gains.

On the right, about 16:45, Gracie had brought up his one reserve regiment, his old 43rd Alabama. At first they made the same mistake as the 63rd Tennessee and Humphrey's brigade when they stepped out into the open field, only to take murderous fire from the two batteries serving grape salad a hundred yards away. So Gracie pulled the 43rd back, reformed them, and sent them up the hill under the cover of the woods toward Hill 1. Joined by the 2nd Alabama Battalion, they drove back the 19th Illinois and 11th Michigan about fifty yards. Then they settled in behind the reverse side of the Yankee breastworks to exchange fire with the Illinoisianians and Michiganderites (or whatever their unwieldy demonyms are). And so a second salient on the ridge had been taken, at least temporarily.

Thomas leaves Snodgrass in capable hands.

With his troops running out of ammunition (even after Granger's resupply), Thomas recognized by this time that he was probably not going to hold out until after dark, which was two hours away. Reassured by Rosecrans's newly returned chief-of-staff, Garfield, that the bulk of the Army of the Cumberland had made it safely back to Rossville, Thomas decided it was time for him to start packing up his remaining troops. Leaving the defense and retreat from Snodgrass to Brannan, he galloped over to Kelly Field (only about three minutes away) to start managing the retreat of the four divisions still there.This would be conducted in a sequence of fighting withdrawals from the south to north, a difficult maneuver. Any panic or mistake on the part of one regiment could precipitate a wholesale panic and rout. So the complicated withdrawal had to be micromanaged by Thomas. Fortunately, at this time, Polk had not been active against this front for a couple of hours, so it was better now than later.But this was another chapter in Chickamauga. Thomas doesn't return to Snodgrass for the rest of the day. And this post is about that battle. So we'll leave Thomas and go back to the hill.

17:00, 6th Assault

After Thomas had left to go do his thing over in Kelly's Field, and after Gracie's attack had achieved its limited success. Bushrod Johnson decided to have one more go. Disgusted with the half-hearted attempts by Hindman's brigades (Deas and Manigault) earlier, Johnson rallied his own three, thoroughly depleted brigades (Sugg, Fulton, and Coleman) and led them up the ravines and hills again. He shuttled his men more to the left, still knowing the Union line was in the air over there, and for the third time led them up the woody slopes, feeling for Steedman's lines. They were joined on their left by two regiments of Manigault's, the 28th and 34th Alabama, who were themselves not half-hearted by far.It was a difficult assault to manage. In the dying light (the sun had already dropped below the hills) and smoke-filled woods, all semblance of control evaporated. The whole mass, of some 2,400 men remaining, dropped even a pretense of moving in ordered lines and crept up the slope as a mob, regiments mingling willy-nilly.

Steedman's division was fresh out of bullets, though. As soon as they sensed another attack coming up against them and outflanking their right, the Yankees called it a day and began to fall back to the next ridge to the north. Steedman tried to stem the stampede as best he could. Intercepting the 115th Illinois on the left, he ordered them to turn right around and go back to their posts. Their commander protested that they were out of ammunition, but Steedman cavalierly told them to just "fix bayonets" then. Dutifully they did that and marched back to their previous position. But they were met by the oncoming Confederates of Sugg's brigade, who fired on them. Since they couldn't return fire, they turned around again and re-retreated.

Johnson's men, pretty exhausted themselves, must have been terribly relieved there wasn't going to be another firefight. They gratefully let the Yankees head off into the gloom and collapsed on their former positions on the crest. They now had the Union right flank and were content to just sit there.

18:00-19:00, 7th and Final Assault

By 18:00 it was getting pretty dark. Though the sunset wasn't actually until 18:42, by this time it had set behind Missionary Ridge and Snodgrass was in deep shadow, made deeper by the woods. And all the firing all afternoon had created a literal "fog of war", the smoke just hanging under the canopy of leaves. So it was hard to see anything.Johnson had finally secured the western flank of the Union line, but we wasn't making any more moves to roll up that line. Steedman's division had retreated on its own and was in the process of rallying, not to reenter the fight, but to march off back to Rossville. All of the troops, in fact, on Horseshoe Ridge and in Snodgrass Field, were starting to form into columns and go while the going was good. Brannan had grabbed four regiments, the 35th Ohio, the 9th, 68th, and 101st Indiana and posted them to act as rear guard for the whole retreating force.

Fortunately, the Confederates themselves seemed to have had enough too. Gracie's two regiments, which had occupied the breastworks on Hill 1, fell back to join the rest of their brigade on the lane at the bottom of the hill. They were out of ammunition themselves and weren't sure they weren't going to be counterattacked by fresh Union troops, of which the enemy seemed to have an inexhaustible supply. Kershaw, Humphreys, Anderson, and Hindman, weren't going anywhere. Only Kelly's small brigade, clinging to the ground just below Hill 3, was hanging on, exchanging ineffective fire with the remaining Federals on Hill 3 until they also ran out of ammunition. One of those regiments, the 58th North Carolina, had crept up again after its previous repulse but was thrown back again by surprise reappearance by the murderous 21st Ohio (firing off their last rounds) and a short charge by the 9th Indiana.

Everybody on the Union side was packing up and moving out in good order.

Well, almost everybody.

This is where my ancestor comes in. The two orphan regiments under Whitaker, the 89th Ohio (in which my great-great-grandfather, Fletcher Hill, was a corporal in K Company) and the 22nd Michigan, had been placed at the western flank of Hill 3 and had been fighting there for over three hours, taking terrible casualties, using up all their ammunition, and shooting with increasingly hot and fouled rifles. Originally, these two regiments had been temporarily assigned on loan to Whitaker by Rosecrans to aid in the Reserve Corps'--well--shall we say, reserve duties. They weren't organically part of that corps except for the duration of this battle. Now, as everyone else was gone, the senior officer of the two regiments, the 22nd's Col. Heber Le Favour, ordered everybody to get up and retreat too. As they were heading back, a passing staff officer of Steedman's (who had long since departed) demanded of Le Favour where the hell he thought he was going? Le Favour replied that his men were out of ammunition and following the rest of the brigade. The staff officer (a major, but feeling he had the authority of a general), ordered Col. Le Favour back in the line and told him to just have his men fix bayonets. He promised him that ammunition and reinforcements would be sent soon. Then rode off to Rossville. Don't know if he even tried to keep his promise.

So Le Favour reluctantly led his two lonely regiments back to the top of Hill 3, where they did as they were told and fixed bayonets.

Around this time, too, the survivors of the 21st Ohio, who were also out of ammunition and had been fighting furiously all day, were down to a hundred men left with the colors, and had only fouled weapons left. They too were found marching to the rear when they were intercepted by a passing Col.Van Derveer (not their brigade commander) and ordered to get back in line. Van Derveer apparently didn't even promise ammunition; just that they too should fix bayonets. The meme of the day. He bravely left for the rear too.

So the three forlorn regiments, not a round between them, settled in behind their previous breastworks and waited. The didn't have to wait for long.

About 18:30 Col. Trigg, Preston's last brigade--in fact the last brigade in the whole of Bragg's army who hadn't done any fighting that day--came up. They were sent to fill the gap between Kelly's left and Sugg's right, at the western foot of Hill 3. Trigg took a few minutes to line his three regiments up (his fourth, the 1st Florida Dismounted Cavalry, had gotten lost and was way over on the eastern flank of Longstreet's force). Then he began moving up the slope, slowly, carefully. It was already quite dark.

With the sun now well below the ridge to the west, it might as well have been night under the trees, though official sunset wasn't for another ten minutes. Everyone on the Confederate side was wary of friendly fire, which had been happening all day as brigades and regiments stumbled into each other from all directions in the jungle. Kelly was warned by Preston that Trigg was coming up on his left and to be careful of firing at the first thing that moved. At one point, someone in the 5th Kentucky (CSA) saw some dark forms ahead and challenged them "Friend or Foe?" The answer was "Friend!" (What a stupid challenge. Didn't these people use call signs?). Then the unknowns let loose with a volley (the 21st Ohio's last round). This infuriated the chivalry-obsessed Confederates as treachery, but what did they expect? They were in the middle of a shooting battle and had been killing each other for three straight days. Besides, the accent of the shouted question probably gave them away as Rebs.

As Trigg's men crept up the hill, the Yankees saw movement in the darkness. Wary of firing into friendlies themselves, Maj. McMahan, acting commander of the 21st Ohio, sent a captain down to see who they were (why didn't he just ask "Friend or Foe?"). When the captain didn't come back (he'd been captured), McMahan sent another officer, who also didn't come back.

Farther down the line, Col. Le Favour also noticed movement below his 22nd Michigan. Rather than sending someone else, he went himself, and was captured. Now, considering the risk of friendly fire was zero since nobody, by this time, had any ammunition, one wonders why these people thought they should send people in harm's way to find out if they were about to be overrun or not. But my ancestor, Fletcher Hill of the 89th Ohio, said that the hesitancy to fire, particularly on troops coming up behind them, was because they had been promised relief by that above-mentioned, transient staff officer, and expected it momentarily.

About 19:00 Trigg's men, with Kelly's on the opposite flank, had completely surrounded the three abandoned regiments. There was a lot of shouting as Confederates demanded "Surrender, you damned Yankees!" Many did (including including my great-greatgrandfather) but many also managed to slip away in the darkness. The 9th Indiana, posted on Hill 2 by Brannan to act as rear guard, heard all the calls to surrender and let off a volley into the darkness. While this apparently didn't hit anyone (friend or foe), it triggered pandemonium, during which many more Federals got away. Trigg heard this fire and sent off an aide to ride over and find out if it came from a friendly unit, and to tell them to stop. When the aide found the 9th and saw that they were the enemy, he demanded that they surrender too. They shot him instead. Treacherous Yankees.

So, after a whole afternoon and seven assaults, Snodgrass Hill was finally taken. Hodor had held the door long enough for the Army of the Cumberland to get away. And the Battle of Chickamauga was finally over.

- You'll remember that earlier Thomas went over to Kelly's Field to extract the four divisions still defending there. That itself was another remarkable tactical tour-de-force, and he largely got most of those troops out safely too, even after Polk renewed his attack when he saw what was happening. But that's another post.

What now for Bragg and the Confederacy?

With Thomas' help, Rosecrans did manage to pull the bulk of his army back safely to Chattanooga, fortifying that city. Lincoln, ever the thoughtful parent, sent a nice telegraph to buck him up, saying how proud he was of him and his men in saving the army. But to his secretary, John Hay, after reading one of Rosecrans' replies in the War Department telegraph office, Lincoln remarked that he sounded "confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head." Lincoln had the best way with words.Bragg also helped the Union cause by remaining immobile for several days. Longstreet, enthusiastic over his victory--he hadn't been this happy since Gettysburg--tried in vain to convince Bragg that he had actually won the battle. Partly because of the horrific cost (16,215 Union casualties to 16,808 Confederate), but also due to Bragg's inherent morose nature, and the fact that this would be his first victory in months, the commanding general just forgot what victory felt like. Forrest, who was pressing the retreating Yankees on his own, also tried in vain to get Bragg to get out of bed and destroy Rosecrans while he was on the back foot, and before he had fortified Chattanooga. But Bragg wouldn't budge. "What does he fight battles for?" Forrest asked no one in particular on his staff.

Forrest and Longstreet were right. By the time Bragg eventually moved up his army and surrounded Chattanooga on three sides, the Army of the Cumberland was fortified and reinforced, and its lines of supply from the west bank of the Tennessee secured. Bragg did have a good excuse in that he had no pontoons to bridge the Tennessee River, so he couldn't seal off its far side. But there's no evidence that he tried to obtain any bridges either. Every day Union reinforcements were pouring into Chattanooga, gradually increasing their numbers to even greater levels than before the battle..

U.S.Grant was appointed overall commander of the West and dismissed Rosecrans, (probably to his relief as well as dismay) and named his replacement as Thomas. About time. By late November, just two months after Chickamauga, the Army of the Cumberland had grown to over 72,000 while Bragg's Army of Tennessee had dwindled to just 49,000. From November 24-25, Grant and Thomas threw Bragg off Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge overlooking Chattanooga. And the invasion of Georgia began in earnest.

So the Battle of Chickamauga, the greatest Southern victory in the West, gave the Confederacy just two months more life, and didn't do a thing to persuade foreign powers like Britain or France to intervene on its behalf. After Gettysburg and the fall of Vicksburg, Chickamauga proved to be such a Pyrrhic victory that the Confederacy was abandoned by all of its erstwhile allies abroad.

As for the fate of my ancestor...

So what happened to the men captured on Snodgrass?After the ruckus from the 9th Indiana's half-hearted rescue attempt died down, order was restored. Though the three Federal regiments were technically captured whole, including their flags and commanding officers, quite a few managed to escape and rally back in Chattanooga to continue the war under their regiments' names. In the 89th Ohio, my ancestor Fetcher Hill's regiment, of the original 389 that had marched south from Rossville that morning, 19 were killed, 63 wounded, and 171 captured, which meant that 136 fell in for roll call at Rossville the next day. Of the 22nd Michigan, 66 mustered the next day. And of the 21st Ohio, who had suffered the most at Snodgrass (but had fought the longest), of its original 561 men, 318 reported for duty in Chattanooga. So these units were, by no means, wiped out.

My GGG Fletcher Hill relates in a long, serialized memoir, "A Prisoner in Dixie", he wrote for a magazine years later, that the surrendered men were all marched off in the dark that night by men of the 54th Virginia, who, he remembers, were very kind to them and gave them all water and let them keep their food and personal items--mutual respect between fighting soldiers. The next day, however, they were handed over to what Hill calls "Home Militia", not front line combat troops, who abused them all the way to Richmond. "They were devoid of everything that went to make up a human creature," he described them, confiscating not only all their food, but their personal possessions, including letters, photos and "likenesses" of loved ones, locks of hair, wedding rings, keepsakes, and other mementos. They also cursed the prisoners repeatedly, he reported, and wanted to "show you'uns the folly of stealing negroes." An odd remark when one considers that after the war, Lost Cause politicians and apologists said the War was emphatically not about slavery, but States' Rights. Well, yes, states' rights to maintain slavery.

After six weeks incarcerated in the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond, where 121 of the 171 captured in the 89th died of starvation and disease. The survivors were moved down to another POW prison in Danville, Virginia, from which he and sixty other prisoners escaped that same night. Only four made it back. He describes in his memoir that though he and his fellows were constantly dodging Confederate Home Guard on their 253 mile odyssey through Virginia, they were helped again and again by friendly pro-Union civilians, disgusted by their own state government's secession. Several Confederate deserters, Unionists themselves drafted by their state, also helped and guided them. Reading his account, it becomes apparent that there was widespread disaffection in the South for the Confederacy, many describing it as an autocratic state. He also described being helped many times by heroic Black people, who were enthusiastic to do what they could for the fight for their freedom.